The artist who has long been described as the “youngest member” of the Fort Worth Circle art group of the 1940s turns 89 this year.

These days, art enthusiasts are more likely to refer to George Grammer as the “last living member.”

Grammer isn’t as prolific as he once was after spending eight decades creating thousands of works.

“I still paint and draw but not with the same satisfaction I once felt,” he said.

Enthusiasm, however, is on the rise among his collectors. No fewer than three exhibitions in Fort Worth are showing his work. The most inclusive is next week at the artist’s alma mater, Texas Wesleyan University, where Grammer attended from 1945 to 1947. The school is presenting him with an honorary doctorate and featuring more than 100 of his paintings and lithographs as part of George Grammer: Full Circle, April 24-28 at the newly created permanent gallery at the Bernice Coulter Templeton Art Studio on campus.

About three-dozen private collectors loaned their paintings for the show.

“I’m amazed at the willingness of all the lenders,” said BB Moncrief Wiese, who is co-curating the show with local antique dealer Carter Bowden. “They are more than happy to loan their art. That speaks to who [Grammer] is. It speaks to his art.”

Bill Bomar, Cynthia Brants, Blanche McVeigh, Dickson Reeder, Bror Utter, and the other Circle members are gone now. That list includes Grammer’s most influential teacher, Kelly Fearing, who died in 2011 at 92. Fearing taught art at TWU in the mid-1940s and familiarized Grammer with modernism. Historians credit Fearing and the Circle artists for being pioneers in the Texas modernist movement. Their Cubist, experimental, whimsical, and sometimes just plain weird creations were light years away from the impressionist scenes of bluebonnets and cactus fields that ruled the day.

Even big-city Dallas artists were slower to embrace modernism than the dozen or so Circle artists who made it their calling. They worked, played, and partied together. Soirees were held in the Reeder home with the staunch encouragement of Sallie Gillespie, an artist and secretary of the Fort Worth Art Association in the 1940s. That group was dedicated to cultivating, preserving, and displaying local art.

Grammer, a rather unworldly young man at the time, fell in with the modernists who were 10 or 15 years his elder, although still fresh in spirit.

“I was younger and very naïve except on the painting and drawing,” Grammer said in a recent phone call from his Manhattan apartment, where he and his wife June moved in the mid-1950s. “I loved being with those people. They were all very friendly and generous and hard-working.”

Nobody referred to them as the Fort Worth Circle back then. Brants coined that term many years later to describe the scene and the artists who were casting conservative Cowtown as the unlikely birthplace of Texas’ indigenous avant garde.

Grammer puts it more simply. The Circle merely refers to a “certain group of old timers,” he said.

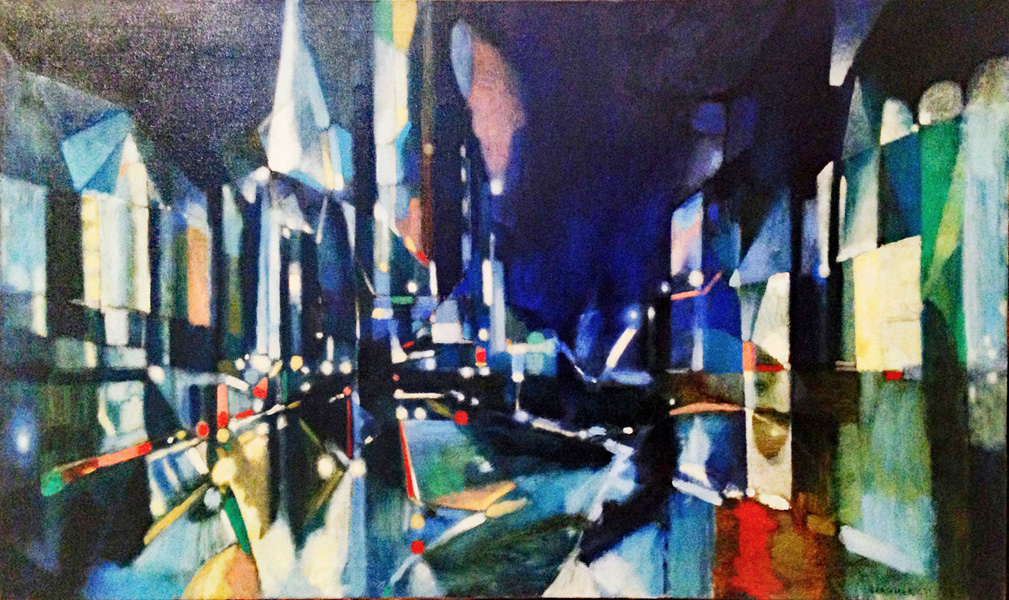

The youngest old timer moved to New York more than 50 years ago. He painted a wide variety of subjects, many celebrating his love of light, reflections, and vertical shapes, particularly Texas oil derricks and New York skyscrapers. Though a longtime New Yorker, Grammer visits his hometown a couple of times a year. He is hitting town soon to press the flesh and shoot the bull at the various exhibits showing his work.

Grammer is modest about his career (and not particularly verbose) but enjoys engaging people who support Texas art and keep him and his Circle buddies alive in spirit. His ability to paint images on canvases that are stretched, framed, and sold for thousands -of dollars is satisfying, but you get the feeling Grammer would have been an artist whether or not he ever sold a single piece.

“It’s been my compulsion since childhood to draw and paint,” he said. “You’ve got to want do it –– and then practice.”

The big-dang wangdoodle of early Texas art symposiums is coming to Fort Worth and will be taking full advantage of the various Grammer exhibits along with the artist himself. The Center for the Advancement and Study of Early Texas Art, or CASETA, is hosting its 15th annual event April 28-30 at the Fort Worth Community Arts Center. The event draws hundreds of art lovers, collectors, dealers, museum professionals, and teachers to town to discuss all things art.

Fort Worth art historian Scott Barker has organized an exhibit similar to the one at TWU, although his will include many different Texas artists. Recuerdo: Early Texas Art from Fort Worth Collections is on exhibit through April 30 at the FWCAC and features 57 works of early Texas artists that have been borrowed from private collections throughout Tarrant County. Barker chose two of Grammer’s works, including one featuring an oil derrick at night.

“His longevity is really starting to make him stand apart from other artists,” Barker said. “He has been at it so long and has been so relentless in his pursuit of it.”

Barker decided to curate a show in conjunction with CASETA and display it in the same facility, renting space and borrowing paintings to complement the big weekend.

“There will be more than 200 collectors here from all over the state,” Barker said. “They like to see local work. Sometimes they go visit private homes. I thought if we bring the art to them, they don’t have to go out to too many houses.”

Oil derricks have always been one of Grammer’s most popular subjects among Texas art collectors, Barker said.

“When you look at his oil derrick paintings, you know they are oil derricks,” he said. “But he has presented them in a new way. They are presented as sort of fractured panes of light. Most of his paintings are based in the real world, and you know that when you see them. But he presents them in a unique way. It’s a George Grammer representation. It’s a style he developed that is unique to him. He is as talented as any artist in that [Circle] group.”

Grammer learned his style right here. He discovered his fascination with oil derricks while making regular bus trips from Fort Worth to Jacksboro to teach art classes in the 1940s. He often made the trip at night and would relish the sight of oil derricks strung up with colorful lights, reaching high into the night above an otherwise flat, unremarkable terrain.

Barker said, “It’s incredible to me that the lessons he learned here transferred so well to depicting the urbanism of New York.”

Incredible is right, considering Grammer was among the poorest of the Circle bunch, growing up during the Great Depression in a family that couldn’t afford something as frivolous as paint.

Pencils and crayons stood in for paints and brushes, and Grammer’s family improvised when it came to finding canvases for their budding artist.

“My grandmother saved cardboard that came out of shirts from the laundry,” he recalled. “She’d save those for me to draw on, and I loved that.”

Eventually, Grammer was able to buy oil paints but not canvases.

“I painted on window shade material that was linen-like,” he said. “I would cut a square off that. I was always struggling to get materials to work with.”

Small in stature but keen in mind, Grammer graduated from Paschal High School at 16. The school’s art teacher, Creola Searcy, had groomed her star student’s talent and helped him earn a college scholarship. He was 17 when he enrolled at TWU.

By mere chance, he would get to train under one of the Circle’s daring members. Fearing would teach at TWU for only two years before heading to the University of Texas in Austin to begin his long tenure there.

“At the time, [Fearing] was only 28, but I thought of him as an old professor,” Grammer said.

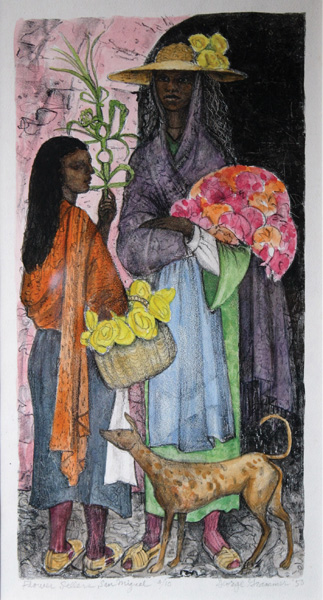

Fearing stressed his love of using symbolism, Cubism, and abstract forms to communicate ideas. Much of it was new and fascinating to Grammer. He practiced the technique and entered a piece in a national competition for a scholarship to attend an art school in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico.

“I won the scholarship but had very spare funds,” Grammer said.

An art patron in Dallas paid for his expenses in exchange for original paintings.

The Mexico trip was fun. But, according to Grammer, the time there was not particularly crucial to his budding style.

“I had a very rich and heady experience at [Wesleyan], and by the time I got to San Miguel, I felt like I almost could have taught the classes,” Grammer said. “I knew what I wanted to do by that time.”

He won a national art competition while in Mexico that included a year of study at The Art Students League of New York, the prestigious training ground for such renowned painters as Georgia O’Keeffe and Jackson Pollock. A couple of years later, the Dallas Museum of Art added a Grammer painting to its permanent collection. The artist’s talent was earning recognition.

In 1954, Grammer married the love of his life, broke away from his hometown, and headed for the country’s biggest art mecca. A half-century later, June is dead, and Grammer thinks sometimes about moving back to Fort Worth. But not yet. Maybe when he’s 90. Or 100.

“New York is a fabulous place for anybody interested in the arts, painting, drawing, music, theater,” Grammer said. “As long as I can climb my two flights of steps to my apartment … everything is right around the corner.”

He is a wonderful artist and human being!

Yes of course he is a great artist too and very soft spoken person.