If cynicism were a type of radiation, you’d probably need to wear a special suit just to talk to Tim Locke, but for anyone who’s even acquainted with the veteran singer-songwriter/bandleader, it’s part of what makes him endearing and a lot of fun to be around. Because even with the dark clothes, the fidgety, self-conscious earnestness, the self-deprecation, and the bleak realism, he’s a pretty funny dude, the kind of person who can elucidate life’s absurdities with subtly scathing, hilariously wry specificity – Tim Locke making a joke about something is like highlighting an errant homonym by drawing a box around it with an X-ACTO knife. Beneath all that pessimism is a guy who likes to laugh, but that sense of humor is also like a layer of flooring over an undeniably existentially shaky base. I figured this out because when I asked him why he has moments of doubt about making music for a living and, specifically, making music with Calhoun, the indie rock band he’s led for 13 years, he cracked a sly is-he-serious-or-not? grin and said, “I mean, what’s the point?”

It’s hard to keep most things going for that long, not least of all a band, and certainly not one that’s come close to the big time. Calhoun is still on a pretty good run, though. On a local level, they always draw sizeable crowds, and they always play enviable slots. Just this past Sunday, a year or so after they last played, they opened for ’80s pop rockers The Fixx at the Granada Theater in Dallas. But after years of almost making it, and despite writing and recording a new album that’s arguably their best yet, Locke wasn’t sure he wanted to even bother putting it out.

“What was the point?” he repeated, again slyly.

Locke and I were chatting at the Boiled Owl Tavern, sitting opposite each other in a booth, sequestered from the happy hour crowd at the bar, shooting the shit about his kids – Henry, 8, and Charlotte, 3 – and our bands (Oil Boom, Son of Stan, and Darth Vato for me at the moment) and the weirdness of aging, like how you look up and realize your parents are in their 70s or your niece is en route to her freshman year in college. Or, for that matter, the way the years go by when your band has been around for well over a decade. The passage of time weighed heavily on Locke, enough so that he thought seriously about hanging up his guitar for good a few years ago. In a HearSay column from 2009 (“Calhoun Redux,” Sept. 9), Locke and company very nearly folded after enduring the promotion cycle for their third album, 2007’s Falter. Waiver. Cultivate, even though Locke and songwriting partner Jordan Roberts had mapped out a bunch of new songs in the album’s wake. In the story, Roberts said, “I’m not sure that we will ever perform any of [the new material] live or ever again, for that matter.”

But whatever doubts may have been lingering were brushed away in 2015, when the band started writing new work. Recorded the following year, Football Night in America came about in an uncharacteristically democratic, full-band effort during a pair of writing sessions in a cabin in New Mexico. The band members are universally stoked about it, and Locke describes it as the “most intensely downer record” he’s ever produced, which, for someone whose brain and soul are wired like Locke’s, is like Dirk Nowitski boasting that he’s found a way to sink 180-degree jumpers from half-court 10 out of 10 times. Yet for all those positives, Football Night in America almost didn’t air.

“I really wasn’t gonna put the record out,” Locke said. “I was happy with it, but I just didn’t see the point.”

The notion of grinding out the shows and promotion without an endgame held little appeal for him. “I’ve been doing it for a long time,” he said. “Whenever we were gonna do something, it was like, ‘We’re gonna try.’ If the opportunity presented itself, if it was reasonable and made sense, we were gonna do it. And I think we’d reached a place where we weren’t necessarily gonna do that at this point in our lives. I’m not in it to play Saturday and Sunday. If we have to go out, eat cat food, and play in a toilet for three weeks … I’ve done it so many times, I’m used to it, at least if I see a vine to swing to, y’know? I just didn’t feel that way anymore. Because I’m old, and we’ve done our thing. It’s like, ‘Does anyone really need to hear another Calhoun record?’ ”

That sentiment might sound fatalistic, but it’s also a very realistic view about being in bands from a veteran musician. Long before Calhoun, Locke almost hit it big during the ’90s alt-country boom with a Dallas band he fronted called the Grand Street Cryers, who broke up in 2000. Locke dived back into the scene with another project, Blue Sky Black (a name that referenced a Grand Street Cryers song, incidentally), and after that folded, he started Calhoun in 2004 with Cryers drummer Max Lintner, jazz bassist Byron Gordon, and Benroi Herring on pedal steel, releasing their debut, The Year that Never Was, that year.

Photo by Vishal Malhotra.

Calhoun followed up their first CD with a lineup change and an eponymous album in 2006, but they really started to find their sound with Falter. Waiver. Cultivate, produced by Stuart Sikes, himself a hot commodity at the time, having made the White Stripes’ White Blood Cells, not to mention winning a Grammy for engineering Loretta Lynn’s 2004 album, Van Lear Rose.

“We got good press with that,” said Locke, of Falter. Waver. Cultivate. “We toured a lot and got music on TV shows, that kind of thing.”

That third album also found its way into stores all over the country, courtesy of Fontana Distribution, a subsidiary of major label Universal Music Group. At the same time, Locke also joined local alt-rockers Flickerstick, who had maintained a fairly dedicated fanbase despite the implosion of their own major label record deal in the early aughts. Flickerstick frontman Brandin Lea, Locke said, “was nice enough to put us on their tours, so I would be doing double duty. It was fun.”

All of that road tripping wore him out, he said, but not enough for him to truly give up music for good. The songs he wrote with Roberts after Falter ended up becoming 2011’s Heavy Sugar. Whatever burnout Locke and Roberts were feeling, Heavy Sugar got them amped again, Locke said. But Locke had also become a dad in the meantime. Along with all of the other anxieties intrinsic to new parenthood, he said he was sort of looking at his own reflection. That’s when he realized he was a band lifer.

“Even when I was in my early- to mid-30s, I was like, ‘What else am I supposed to do? This is it.’ And I never saw myself as the old guy in the scene. And now I’m like, ‘I’m the old guy in the scene.’

“I saw the new bands coming out around here,” he continued, “and I thought, ‘I’m really old, and it’s time for me to step aside.’ And I’d kinda already stopped going out. After the Flickerstick thing, I was kinda ready to be done. That was like 2008 or 2009 … And then we made Heavy Sugar in 2011. I wrote all those songs when Henry was born, around 2009. And after that, I was like, ‘Man, I’m so old, so tired, so scared.’ ”

I asked him if he had thought Calhoun’s music was dated or out of touch. He laughed.

“No,” he said. “I never thought that, though maybe I was being naïve. But you see what the kids are up to – like, ‘Do I wanna be that guy doing this?’ Because I remember being 24 and seeing [a guy like] me now and going, ‘Dude, what are you doing here? Go home. Raise your kids. Get out of here!’ So it’s weird to be that guy. But that doesn’t mean I think our music isn’t good. But I also think Fort Worth has a crop of bands right now that are really good, and that’s kinda when I’m like, ‘Why am I doing this?’ ”

Locke may have gone deep with his self-doubts after Heavy Sugar, but the way by which Calhoun went about writing Football Night in America renewed their creative energies. The band basically went on a couple vacations. Locke’s family owns a cabin in Ruidoso, N.M., and in 2015, Locke and Roberts with the rest of Calhoun – bassist Danny Balis, drummer Josh Hoover, and keyboardist Toby Pipes – holed up for a few days to hang out and try to come up with some songs.

“It was fun,” Locke remembers. “We set up a full PA in the basement of the house, and there were maybe four or five songs we had blueprints for, but then the rest was … ‘jamming,’ ” he said, making air quotes. “And a lot of that was awful, but some of it, I thought, ‘Man, I remember why I liked doing this.’ We had a blast.”

“It was fun,” Locke remembers. “We set up a full PA in the basement of the house, and there were maybe four or five songs we had blueprints for, but then the rest was … ‘jamming,’ ” he said, making air quotes. “And a lot of that was awful, but some of it, I thought, ‘Man, I remember why I liked doing this.’ We had a blast.”

For Locke, getting together with his friends was what made crafting an album fun again, he said. A few days before their Granada show, they gathered at a rented practice room in the Fort Worth rehearsal space The Loop, where I interviewed them and a slightly sunnier Locke. A couple of months after that first Ruidoso session, Locke said, they regrouped at the cabin for another one to make sure they still liked the new material (they did), after which they began the recording process, tracking at several locations: now-defunct Blade Studios in Shreveport, La.; at Pipes’ house in Baton Rouge; and at Electric Barryland in Justin with Jordan “Jorts” Richardson. The process, however, was inordinately lengthy, due mostly to conflicting schedules and geography: Balis is an on-air personality on The Hardline, an enduringly popular drive-time show on The Ticket, Roberts lives in San Francisco, and at the time Pipes lived in Baton Rouge. After the songs were finally recorded, the band met in Shreveport to mix the album with an engineer whose resume included names like Maroon 5, Kenny Wayne Shepherd, and Erykah Badu – only to scrap them later. Locke said that he’d been really happy with how Richardson had everything sitting in rough mixes, but when the final mix came back after they’d worked with the Shreveport engineer, it had an unappealingly slick, “almost Triple-A” radio sheen that undid everything they liked about the roughs.

“We did everything live, and that mix was not what we intended,” Locke said. “We’d never done a record like this before, where everyone was writing. … This time, we went to a cabin in the woods, the five of us set up, we played for three days straight, and came up with the 10 songs … and that first mix, all that just sounded lost.”

The band decided to hand the roughs back to Richardson for final mixing.

“Jorts’ second mix put teeth back on it,” Locke said. “But it took forever.”

Roberts said they gave Richardson sonic references for each song – notably Broncho’s 2016 album Double Vanity – and he would spend a couple weeks on the individual tunes. While Richardson’s effort got the songs to better reflect Calhoun’s visions for them, the production process became even more drawn out. But even after it was finally mastered, the band didn’t rush to get it into anyone’s ears.

Oddly, no one in Calhoun can definitively explain the wait.

“I don’t know what the delay on it was,” Roberts said. “I guess it was just our lives?”

Hoover said they spent time shopping the album to various labels, and Roberts agrees that this put the release date further into the future. “We wanted to do our due diligence with it, get it out there to people, and after you send it out to a bunch of people and no one responds, you’re like, ‘Fuck it. Let’s just put it out.’ ”

Enter: Idol Records, the small but powerful Dallas label that has put out a ton of North Texans (from The O’s and Dove Hunter to the Deathray Davies and Centro-matic), as well as Calhoun’s Heavy Sugar. Idol happily pressed Football Night in America on wax, releasing it at the band’s Granada show.

Locke’s take is a little more critical, however. “I’ve always felt like when you make a record, if it sits on a shelf, it just starts to stink. They’re so disposable . You just have to get it out to people. That may not be the truth, where everyone [in the band] feels that way, but that’s how I’m wired.”

Football Night in America does not stink, and even though the tracks are more or less two years old, they feel unintentionally current. Richardson’s production imbues the songs with low-end weight, distorting the bass, dirtying the synths, making the music tense and urgent, even when the songs are in a major key. Locke has never shied away from a hook, and his ear for melody makes a perfect cover for lines like “you live your life of innocence until it starts stalling” (“The Art of Mindfulness”). Locke said the album’s overarching theme is of “feeling isolated and rudderless,” as the life he chose as a musician is characterized by such. On “MNTN Hearts,” Locke sings, “Life is a gift and curse all along / But you have to make it on your own,” which nicely sums up his thesis. As for the title, what started as an eye-rolling bit during their writing sessions became suddenly relevant following Donald Trump’s ascent to the White House.

Photo by Vishal Malhotra.

“It’s funny because through the process, we always kicked around the name because it was such a lame joke,” Roberts said. “We’d finish our writing week, and it would be Sunday, and so we’d watch football games, and they’d always say it during the pre-game show. But it stuck, and as things in the country started to progress, it made more sense, especially with the lyrics [Locke] was writing.”

“I mean, it could’ve been named Ow, My Balls, and it would’ve been just as fitting,” Locke said.

“And also, it’s such a lazy title for a show,” Roberts said. “It’s like [the people at NBC] were all sitting around in the conference room and said, ‘Well, do you have any ideas?’ It’s like Snakes on a Plane but dumber.”

Yet the confluence of Sunday evening’s familial connotations and Dan Patrick intoning, “It’s football night in America” lend an absurd sense of gravitas to something that’s arguably extraneous, a fitting bellwether of the America of 2017, where an NFL broadcast is elevated to the historicity of an FDR fireside chat.

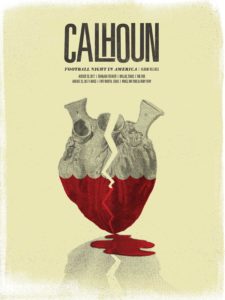

“I mean, even the artwork, we made it so one side is red, one side is blue, but when you unfold it, it’s all one image,” Roberts said. “It wasn’t that we were going for a concept record. It just all ended up making sense. It’s like it became one after the fact. By no means is it political, but thematically, it’s pretty relatable to the way people feel now.”

As for the way Calhoun feels about being a band, they’re going to keep soldiering on.

“We’ve been riding into the sunset for like seven years now,” Roberts said. “There’s no point in being done.”

Locke agrees. “I think if we ever did decide to call it … we wouldn’t tell anyone. We would just be done.”

“We wouldn’t make a big to-do about it, like some Kobe [Bryant] farewell tour,” added Roberts.

Ultimately, Locke figured out that the real reason to keep Calhoun going is because he likes making music with his friends, even if it’s not at the speed and intensity with which they once did.

“I mean, it is weird,” Locke said, “because we haven’t played in a year, and the record’s been done a year. I don’t know what we’ve all been waiting on or doing. It’s been strange, to kind of get us back in our places to get going again.”

“I imagine we’ll eventually get tired of playing all of this shit,” Roberts said. “So, basically, it’s this next week, and then we’ll be done again.”

Everyone laughed.

“But we’ll get sick of doing whatever we’re doing outside of the music, and then we’ll say, ‘Let’s just get together, hang out, drink, get weird, write some new songs.’ ”

Calhoun, Fri w/VVOES, Rat Rios, and Ruby Fray at MASS, 1002 S Main St, FW. $10.