At the top of the stairs is a wall-length pigment print, a punchy cacophony of brightly colored consumer artifacts splayed out in a rainbow gradient. “2017: The Mess” is at once celebration, observation, and critique.

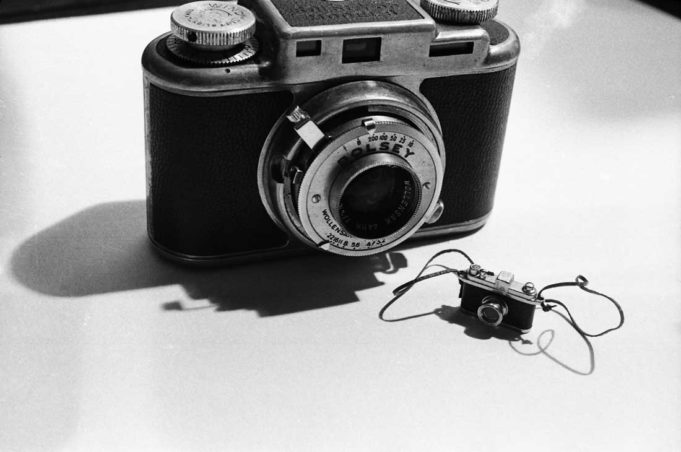

Turning into the main body of Big Camera/Little Camera, a major survey of Laurie Simmons’ photography, the viewer encounters an early series (1973-1975) of black-and-white photographs of the artist’s friends against a backdrop of cherry wallpaper. At the end of these portraits is the image from 1976 that gives the exhibit its title, a juxtaposition of the hobbyist’s camera owned by Simmons’ father with its replica in miniature.

Within these opening images, the viewer may come to a sense of the themes and variations that have shaped Simmons’ production of work over the past four and a half decades. Shifts in scale, the real versus the facsimile, and the intimacy conveyed with the presence (or absence) of the human form interplay with the artist’s interpretation of our shared media landscape, consumer messaging, and the roles and signifiers we are expected to navigate, negotiate, and assume.

“I think that when I started to take photographs, people thought about photography and photographs as being a way to tell the truth,” said Simmons, whose early formal training had been in printmaking and sculpture. “When I picked up a camera, I was really interested in how a camera could lie, how it could deceive us. I was very interested in having the camera be a tool that didn’t speak about the truth but spoke more about my fantasies or even my personal idea about the truth.”

The show features more than 100 pieces documenting the artist’s use of shared visual vocabulary to explore our relationship to our cultural context. Organized by curator Andrea Karnes, and with Simmons’ full participation, the exhibit is an extraordinary opportunity for visitors to experience the breadth of Simmons’ prolific output.

Some of Simmons’ images are so iconic that even casual visitors will have encountered them before. Her series of carefully lit domestic scenes from the late 1970s, using dolls and doll furniture to challenge assumptions of scale, are at once familiar and jarring, turning postwar standards of domesticity into haunting dioramas. Her 2015 series, How We See, plumbs the uncanny valley with vivid portraits of real people, eyes painted onto their closed eyelids, obliquely addressing the one-sided self-commodification of the social media landscape.

“Social media allows us to put our most perfect, desirable, funny, and fake selves forward,” Simmons said, “while naturally raising questions about our longings, yearnings, and vulnerabilities. In How We See, I’d like to direct you how to see while also asking you to make eye contact with 10 women who can’t see you.”

Simmons has staged compositions that blur the lines between mannequins and people, welded oversized props to human legs, and interposed sex dolls into wrenching domestic scenes.

Though much of Simmons’ work over the course of her career has been characterized by her investigations of “women in interior spaces,” her work has not been a one-sided consideration of the limitations inherent in gender stereotypes and archetypes. Simmons’ 2013 series, Two Boys, uses the blank, unconscious adolescent faces of CPR dummies, dressed in hoodies and crouched over laptops in a hospital, to pack the kind of punch that stays with you for days. Her 1990-1992 series, Clothes Make the Man, and 1994’s Café of the Inner Mind use ventriloquists’ dummies to examine both the humor and tragedy of toxic masculinity.

Big Camera/Little Camera is an expansive geography of work, a landscape so lush and impactful that it may be difficult to absorb within a single visit. The work is worth some time, though, and allowing it to sit with you between two or three visits will yield rich rewards. The work explores an interiority that is programmed by external signifiers and runs parallel to our waking consciousness. Along with a biting apprehension of the cruelty imposed upon us by restrictive social norms is the artist’s deep empathy for the humanity that lies beneath the mask.

Laurie Simmons: Big Camera/Little Camera

Thru Jan 27 at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, 3200 Darnell Street, FW. $10-16. 817-738-9215.