Devon Wright is my friend. More than that, he’s like my third son. He’s 28 now, but I met him eight years ago when he joined a trip that I run a couple of times a year taking people out to the deep Amazon jungle for 10 days. Back then, he was a tall, lanky kid with long blond hair. I wondered how he would do out there with no electricity, no cell phone service, no computer, no place to bathe but in a river that’s home to electric eels, caiman, anacondas, and every type of piranha known to man. I’ve been running the trips for nearly 20 years — or variations of them — and my guests tend to be older, generally people in their 30s or 40s, people looking to shake up their lives.

Turns out Devon did alright. He loved hiking in the primordial swamp I took the guests to, loved foraging for wild foods, loved walking in high jungle and going out on the river at night in dugout canoes that could very easily capsize. He took it all in stride: the mosquitoes, the bats, the occasional aggressive bee or wasp, the constantly wet sneakers, even the wretched downpours when there was no place to get inside. He not only went through all that. He kept a smile through it all. I liked him.

Like a number of my guests, he stayed in touch after the trip. He even came to visit me at my place in Joshua a couple of times over the next year or two. He would stay a few days or a week and pitch in around the yard without being asked. One time, maybe four years ago, he cut an overgrown area with a weed eater. The fenced-in patch of 60-by-80 feet was knee deep in long grass and sticker bushes and way too long for the lawn mower to tackle. He just disappeared and several hours later came into the house and announced that he’d cut that yard. I had no idea he was doing it, and when he told me he’d done it with the weed eater, I was damned impressed. I couldn’t have done it.

Over time, he began to feel like one of my sons. Both of them are grown and have lives of their own but come by now and then to pitch in on something that needs doing. I love them, I care about them, but I respect them enough not to pry into their personal lives. If they want to share something, I’m available, but they generally initiate it.

The same was true with Devon. As I was taking him to the airport at the end of one of his visits, he told me he was having problems with his partner. I had no idea that he had a partner. Then he told me he’d been living with his partner, a man, and that he, Devon, had disclosed something that had disturbed him. OK, so I didn’t know he had a partner, and I didn’t know he was gay. It was OK, of course, just news to me.

Devon didn’t tell me what he’d said that had been disturbing. He just wanted me to know that he’d had a long-term relationship and that it was with an older man. When I didn’t flinch, he thanked me for understanding. I told him that there was nothing to thank me for, that short of hurting someone purposefully, there was nothing he could say that would bother me.

“I love you, Devon,” I said. “You’re always welcome in my world. Hell, you’re an addition to my world.”

He smiled and that was the end of it.

Over the course of the next year, he came on a second trip to the jungle with me before relocating to Hawaii, where he had friends. He was making a living doing some kind of life-readings for people, encouraging them to find a path or paths they were comfortable with and having the courage to walk them. While he was living there, he came to visit twice when I had reunions of former jungle guests at my house — a couple of weekends a year — and everything seemed fine with him. He and his partner had broken up, and he was in a good relationship with a woman. He loved where he was living on the Big Island, and he seemed happy.

So it surprised me when he called about a year ago and said he was having problems and would I mind if he came to stay at my house for a while. I told him that would be fine, and maybe a week later he showed up with a small suitcase and a large backpack. I’d cleaned out my son Marco’s old room years earlier and turned it into my guest bedroom, and so I steered him to that and told him to make himself at home for as long as he liked.

He didn’t have money to contribute, but he put himself to work almost instantly. He finished fixing my chicken coop — he and former guests had rebuilt most of it during one of our reunion weekends some time earlier. He also helped another friend and me put in a garden and helped rebuild and paint a shed that I had turned into an office shortly after I moved to Texas. I turned the shed over to him to use as his office. I was using an office in my house, and I wanted my private time to work there, so giving him his own space allowed us both to have some privacy.

Devon kept pitching in, helping haul trash to the dump, helping with recycling, weed eating, cleaning the house, feeding and watering the chickens, going shopping with me for groceries sometimes, and generally making himself an asset.

In the mornings, before he would go to the coop and on to his office, we’d have coffee together. We talked politics, the drug war, projects we were working on, that sort of thing. It was always a nice hour, and we were often joined by my daughter Madeleina when she wasn’t away at college or my ex-wife Chepa, who often came for coffee with her two young daughters.

One morning, not long after he arrived, when we were alone, he grew serious. “I’m not sure how to tell you this, but I’m gender fluid,” he said.

I’d never heard the term before that. “OK,” I said. “And what does that mean exactly?”

“It means that sometimes I’m male, and then sometimes I’m female. Sometimes I’m both at once. Sometimes I change in the course of an hour. Other times I might not change for a few months. It’s not a question of being straight or gay — we’re talking gender here, not sexuality, though they often get tangled up together. It’s not something I control. It’s just who I am.”

*****

The subject came up now and again after that, but it wasn’t until recently that he wanted to go into it from the beginning. For the early part of his life, Devon said he knew nothing about who he was. He was a normal kid growing up in Auburn, Washington, where his father worked for Boeing and his mother worked as an administrator in the public school system. He had an older brother and sister who were pretty close in age and said his upbringing was typical.

“We had a house on Main Street, went on vacations when we could, and so forth,” he said. “I went to public schools and was a pretty average student. I played football, was on the wrestling team, ran track. I did well through my sophomore year but wound up dropping out in my junior year.”

Devon said he had fallen into a bad emotional space. He became depressed and just “gave up on life a little bit.” His family life had grown chaotic. His mother was off and on again with breast cancer, his dad had begun struggling with alcohol, and his brother was in and out of rehabs for drug abuse. “Looking back, it was a good childhood, but it really spiraled out for a few years. I was doing whatever drugs I could get my hands on, but luckily I didn’t suffer the same addiction problems as my brother or dad. I quit sports before I dropped out because they weren’t making me happy — I was just doing them to make other people happy — and the teachers turned their backs on me for that, so I quit school at 17 and went down to the Amazon for the first time to attend a shamanism conference. I was just curious about other ways to live. Unfortunately, I got really sick and pretty much stayed in my hotel the whole time.”

When he got home, he earned his GED and landed a job as a sander and painter with a yacht building company. “It was pretty interesting. On one hand, I was building boats for people with tons of money and whose politics I didn’t necessarily agree with, but on the other hand I got to work on these works of art called yachts.”

He stayed at that for three years and made good money but was laid off in 2011. “That was when I went on the first trip with you. I’d seen your name on the shamanism conference website, and your trips sounded like what I needed. I really wanted an adventure after being in such a down space for a few years. I knew there would be danger and that something could go very wrong — the boat might flip over, I might run into a poisonous snake — but that was a risk worth taking for the experience.”

It was about a year after the trip that Devon realized who he was. “When I was 21, I read a fictional book in which a transgendered Native American character was named Two Spirit. And reading about a two-spirit character gave me that ‘ah-ha!’ moment, the realization that I’d been going through a similar thing for most of my life but couldn’t see it until just then.”

I asked him what the realization meant.

“My first reaction was relief,” he said. “Being able to understand and see myself on a level I’d never done before was like light being shown into the darkness. I felt really happy being able to recognize this. But the more I processed it and began to think this was really true for me, well, that was intimidating. I was afraid to express myself the way I wanted and was afraid of being honest with others about who I really am. I struggled with that for a few years.”

It wasn’t until he was 25 that he told his partner that he was gender fluid.

“He was non-reactive,” Devon said, “which was not the best reaction for me at the time. He basically ignored it. I think it made him uncomfortable. He just didn’t want to address it. It was not a case of a gay man being more feminine and expressing that sometimes. It is someone’s gender identity, which was sticky for him. He was like, ‘You’re not a man, but you’re not a woman either.’ In his world, you were straight, gay, or a cross-dresser. It doomed the relationship.”

Once he had a name for it, two spirit, Devon said he realized that he’d struggled with it even as a teen. “Am I a woman? Am I a man? I’d go from feeling all male energy, and then it would shift to female energy. I tried to shut it out for the most part and ignore it, but after that first trip to the jungle, I found it harder to ignore. I just felt fully manly sometimes and then fully woman.”

The relationship with his partner was not the only one ruined by Devon’s acceptance of himself as transgender. Someone in Hawaii, a close friend with whom he worked, was so upset when Devon told him that it made working together, or even sharing a physical space, impossible.

“That’s why I asked you if I could come stay with you a while,” he said. “I just couldn’t stay there any longer with such anger directed at me.”

*****

The transgender issue might not be familiar to all of us, but it is something that people, very frequently teens, struggle with on a daily basis. Suicide is the No. 2 cause of death for people between the ages of 10 and 24 here in the United States, and while it is impossible to know why each of those teens took their lives, we do know that a good number of them have sexual issues. Some are kicked out of their homes when they come out. Some are bullied or beaten up at school. Others face religious intolerance.

Sharon Herrera knows about religious intolerance. At 16, she was told by a Catholic priest that she was going to hell for being gay. Herrera, who is now 55, said that the priest’s comment led to her suicide attempt.

Herrera said that after the priest told her she was doomed to hell for being gay, she prayed. A lot. “My knees were sore from kneeling and praying to God to change me,” she said. “I could not go on, being ridiculed and not being accepted as a human being.”

There were no guns or drugs in her home, so Herrera decided to kill herself with Drano — which would have been the most awful of deaths.

“What stopped you?” I asked.

“I had a cup of Drano in one hand and a bible in the other. And then my Aunt Margaret walked in on me and said, ‘I know, mi hija, you don’t like boys.’ And those words saved my life. She was good with me being me, and I was good with that too.”

Herrera said that 40 percent of people in the LGBTQ community try to commit suicide between the ages of 10 and 24. “It’s the second leading cause of death in that age group, and the number one cause of those suicides is family rejection. … My aunt and I never talked about it again for years after that, but knowing that she loved me and that she got it, that’s the reason I’m here. That saved my life.”

Herrera eventually joined the United States Air Force but even there was made uncomfortable. “It was during the witch hunt period when they — other people in the military — were looking for gay people, and they’d just kick you out. I would have served 20 or 30 years, but I did not want to get kicked out, so I just quit after my four years were up. It was bad. There were so many killings in the military over this. There is so much hate out there.”

When President Obama later lifted the ban on gays in the military, Herrera said she fell to her knees in thanks. “I was too old to rejoin, but I would have. And now we’re dealing with the transgender ban by the [U.S.] Supreme Court. It’s just awful, the hatred, the chaos. When people truly love themselves, they cannot hurt another human being.”

Because of how she felt, Herrera in 2010 founded LGBTQ Saves, a nonprofit with a mission to provide safe spaces for social and personal development in the community — and education to their families.

“These kids are feeling rejection, being kicked out of their homes,” she said. “They are bullied at school, and they are trying to find out who they are in the middle of all this adult chaos going on around them. We create a safe space where they are supported and loved and accepted, which allows the child to have hope and get rid of that negativity. One child told me that when they are here, they do not think about suicide. That’s important, because the majority of the youth that we serve have tried to commit suicide. We have the tools to help these children deal with what they are going through with love an acceptance. It’s what we do.”

Herrera, whose day job is with the Fort Worth school district, provides workplace training as well and works with the parents of a lot of the young people at LGBTQ Saves.

“I always tell people that enemies are just people you don’t yet know,” she said. “A lot of parents say I give them hope, but I’ll say, ‘No, it’s the kids who give me hope.’ ”

The majority of the people with whom the organization works are between 13 and 18, though Herrera said LGBTQ Saves also works with a number of older kids, up to 25, who have been kicked out of their homes. “For the older kids, we try to supply the resources they need to help them become successful in life. We can’t do all we want yet, though, so I hope Ellen DeGeneres reads this and gives us some money to help achieve our goals.”

Currently, LGBTQ Saves offers safe places, events where everyone will be respected, suicide prevention information, and even scholarships to help kids stay in school or continue their educations. “We give four of those [scholarships] a year to kids who have worked with us, some on our website, some with counseling other kids. We would love to be able to do more.”

LGBTQ Saves is by no means the only organization supporting the community in Fort Worth. The Tarrant County Gay and Lesbian Alliance works with lesbians and gay men to lessen discrimination in the area and acts as a voice for the community’s concerns to government, religious and community leaders, and the media. And there are several others.

The City of Fort Worth’s Human Relations Commission also deals with discrimination, including against the LGBTQ community. Veronica Villegas, the commission’s human relations coordinator, said that she doesn’t receive a lot of discrimination complaints from the LGBTQ community with regards to housing or employment and credits that partly to a city ordinance that protects the LGBTQ community. “Not every city has that, and we hope it makes Fort Worth a more welcoming city to the community because of it.”

Villegas, who works in education and outreach as well, said that the school district’s anti-bullying policy is also very strong. “The whole city, and even the county, is pretty determined that people should just be themselves.”

Villegas mentioned the Tarrant County Gay Pride Week Association, which holds an annual 10-day event in early October, and Q Cinema, the region’s only LGBTQ film festival. She added that the first LGBTQ health clinic is about to open in Fort Worth in a community center. “Former City Councilman Joel Burn’s husband, J.D. Angle, is behind that, so we’re very inclusive.”

Of course, Villegas added, “I don’t want to say that discrimination isn’t happening just because we at the Human Relations Commission don’t hear a lot about it. It is an indicator, but it does not mean that everything is hunky-dory.”

*****

Devon, who says that gender fluid people fall under the “T” in the LGBTQ acronym — the “T” is for transgender and is a large umbrella — was luckier than a lot of other people who discovered they fell into the LGBTQ community. Other than his former partner and his coworker in Hawaii, most people, he said, have been receptive to him telling them who he is.

“Except for a very few people, I didn’t tell my family or most of my close friends until last year,” he said, “so it was six years of knowing I was gender fluid before I could come out to them.”

How did his family take it?

“I tried to contact my mother when I finally decided to talk, but I couldn’t get hold of her, so I finally just sent a text message to the whole family. My brother was fine with it. My sister took a little while because she’s very religious, and she had to come to terms with that. I didn’t hear from my mother for a couple of weeks, but when I did, she was supportive. My grandparents were the best. They were fine with me just being me.”

Deciding to tell his family was a difficult decision, he said. “I’ve never even shared that I had male partners with my family, but I was considering transitioning with hormone therapy for a while and moving to take steps toward that, and I wanted to let them know before I started a program like that. I’m glad I told them, but I was scared.”

He later decided against transitioning because he still felt like a man so much of the time.

“And telling you,” he told me. “That was scary. I don’t remember how long it took me to tell you. I might have wanted to bring it up for a couple of years, but it was hard to bring up. I knew you would accept me and love me, but at the same time, there was a huge fear of damaging this relationship by revealing this part of myself. The fear of not being accepted is very real, and it’s very hard to tell the people you are closest with.”

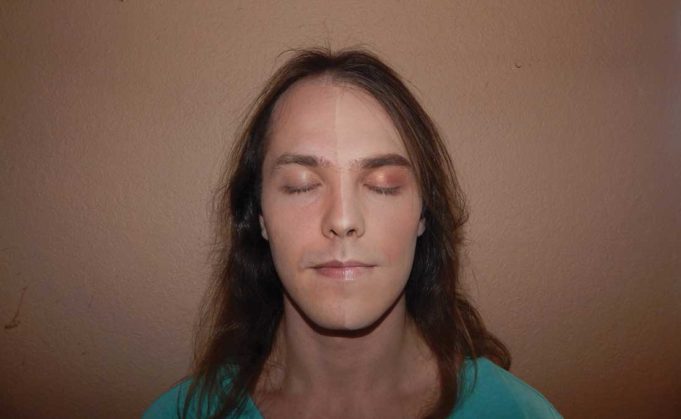

My family and I had no issues with it. When he was here for most of the last year, he sometimes came out of his room with a little bit of eye shadow or a touch of mascara. Sometimes he’d wear a necklace that was a bit feminine or a shirt that plunged. Sometimes I could be talking with him out by the creek bridge, and I could feel him shift. He was still Devon but just a bit softer, gentler Devon. Not effeminate, just gentler. If it were noticeable to anyone, it would have been when he picked weeds in the garden or squatted on his haunches to pet the chickens and ducks. There was something so strong but at the same time very moving about how he related to the birds and the garden. It was striking.

Devon has pretty much come to terms with who he is but still struggles with how other people will receive him. “I’ve gotten better at facing that, just being more confident with who I am and how I decide to express myself, but I still struggle with it sometimes. It shows up with me censoring what I want to wear, depending on the situation I might be in and the people I might be around. Of course, we all censor. We don’t walk around the supermarket in our underwear, for instance, but for me, if I decide to dress too femininely, I sometimes think people will have a problem with that. For example, if I dress as a woman and don’t pass as a full woman in people’s eyes, that’s where the fear comes in. If someone thinks I’m a man who looks too feminine, that’s where the problems arise and the fear raises its head.”

Devon never wore a dress while at my house. I asked him why not if he sometimes liked doing that. I even mentioned that Iggy Pop used to like to dress in women’s clothing because he didn’t think it was “shameful to be a woman.”

Devon laughed. “Iggy Pop could get away with anything. I never wore a dress at your home because you live in Texas, and I didn’t think Johnson County would be the most receptive place for something like that.”

He did wear full makeup — light and tasteful — while shopping on the day before he returned to Hawaii. “When no one looked at me funny, I realized I probably could have worn a dress now and then. I might do that next time I come to stay with you.”

Devon left a month ago, and my whole family misses him. My daughter Madeleina jokes that I finally had a good son, and he left. My ex misses our talks over coffee in the morning. My other kids say it’s too quiet in the house without him. The girls say he was much more fun than I am. And me? I hope he does wonderfully this time around in Hawaii and never again feels he has to leave because of the anger around him for being who he is. But I still miss my friend.

Thank You Peter for sharing your story .I am a gay male 55 Hispanic man.Our lives are once again being attacked by people’s fears of the unknown.Sharing your story hopefully will open minds and open Hearts and homes to the young .Most are pushed away or disowned and or get “the feeling” of being disowned by family .I ran away at 13 to San Francisco . Barely surviving. Just can’t thank you enough for your story .Keep up the conversation Everyone deserves to be Eqaul in the community ! Your Alright Man ✌🏾

You both good medicine people, the world would be the same without ya both brother.

Devon is a wonderful person as soon as I met him I felt his wonderful spirit. I believe he’s here to educate people on the complexity of identify, that identity is just not gay or straight or male and female. Wherever a person falls on the spectrum they are to loved and respected as everyone deserves.

Thank you Peter Gorman for this wonderful story