A relatively new book tells the story of a child of privilege educated at an Ivy League university who changed the United States’ landscape and harbored Nazi sympathies. You would think we’re talking about Donald Trump, but The Man in the Glass House by Dallas Morning News architecture critic Mark Lamster is a comprehensive biography of the late architect Philip Johnson. One of the most influential architects of his time, Johnson was a key figure in shaping the American skyline, including Fort Worth’s.

Born to a well-heeled family in Cleveland, Ohio, Johnson studied philosophy at Harvard before moving to New York City, where he used his connections with upper brass at the Museum of Modern Art to become the first curator of architecture, a position that bears his name. His exhibitions included 1932’s The International Style: Architecture Since 1922, co-curated with Henry-Russell Hitchcock. It was a prelude to his later career as an architect of the style, to describe the trend of restraint: clean lines free of ornamentation.

After leaving the museum and before returning to Harvard to study architecture, he went down a very different path as a populist political candidate, organizer, and Nazi propagandist. He failed to cultivate a political movement but succeeded as one of the United States’ Nazi mouthpieces. When he returned to architecture, this time as a licensed professional, he denounced his past allegiances, but those beliefs lingered throughout his life.

His past remained buried. One has to wonder how his career would have unfolded if politically progressive patrons such as Houston’s John and Dominque de Menil realized the extent of his beliefs. The couple commissioned his first project outside of New York: their house. While he was constructing the iconic glass house in New Canaan, Connecticut, Johnson conceived a one-story, 5,000-square-foot mansion made of brick and steel with large airy rooms wrapping around a central courtyard. Compared to the neighborhood’s Tudor homes at the time, the Menils’ flat-roof home was out of place. Nowadays, it’s pretty much the standard.

Through the couple Johnson met Ruth Carter Stevenson, Fort Worth’s architectural doyenne, who commissioned him in 1958 to design the Amon Carter Museum of American Art and its three expansions. Stevenson commissioned him again in1970, this time for the Fort Worth Water Gardens, the open playground of shapes and angles right out of a science-fiction movie. Johnson and his work partner, John Burgee, however, said the playfulness found at Disney World was the inspiration.

Johnson jolted to fame in that period, becoming the go-to architect for philanthropists and corporate executives. As he became the face of corporate architecture, the country itself was changing with the election of President Ronald Reagan. Johnson also ushered in his own new era of forgettable eye-rolling designs, just what a new era of robber barons wanted, he noted.

His late works lacked a sort of depth and were attractive to none other than Trump, who commissioned and praised him. (My bet is that if Johnson were still alive, the president would have commissioned him to build his library.)

Dallas’ gauche Crescent Center, according to Lamster, was “something altogether worse and without intellectual pretense or rigor, an architecture of staggeringly indelicate historic detailing slapped on leaden structures that made negative contributions to civic space.”

Lamster’s description has more bite than that of his predecessor at the paper, David Dillon, who said, “It seems the product of several architectural visions, which often as not conflict rather than complement one another.”

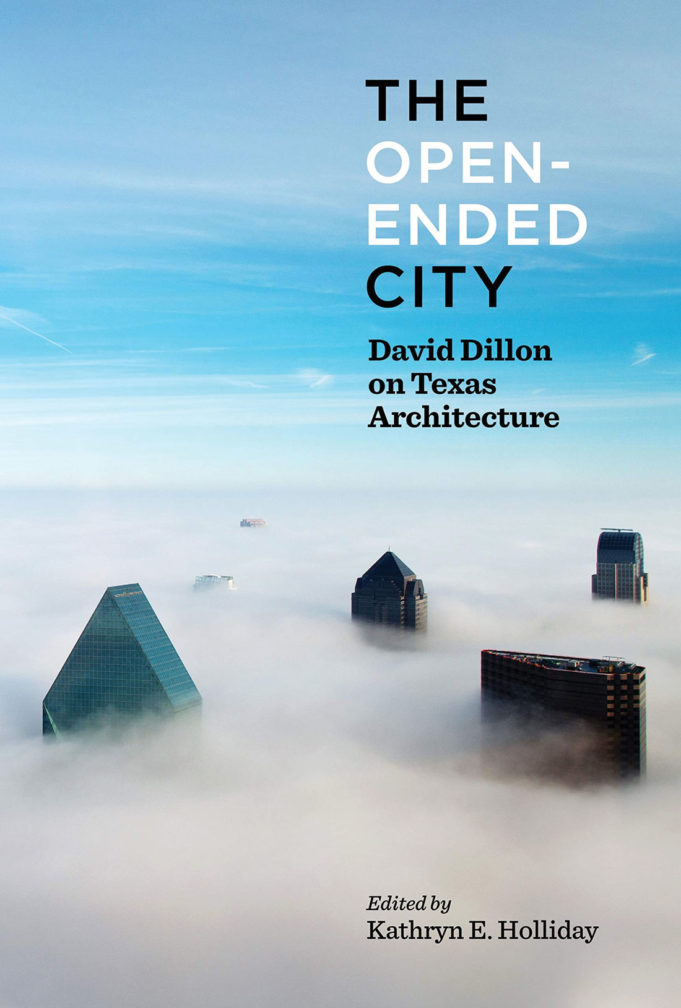

That column is among several in the new anthology The Open-Ended City. Published by the University of Texas Press and edited by Kathryn Holliday, an architectural historian and director of the David Dillon Center for Texas Architecture, the book includes Dillon’s1980 D Magazine debut essay, “Why Is Dallas Architecture so Bad?,” as well as astute commentaries on Dallas’ and Fort Worth’s cultural districts, downtowns, and neighborhoods.

Dillon, who was not trained in architecture, critiqued his city and the region with passion, patience, and warmth, but he was of a different time, no less working for a conservative newspaper. His profiles of developers such as Harlan Crow were fair and his advocacy for urbanism clear, but for a rapidly changing city, his attention remained focused on a certain Dallas architecture: upper-scale residences, corporate headquarters, and arts districts.

He also profiled an array of Texas architects and even dedicated an entire book to one: San Antonian O’Neil Ford, a peer of Johnson’s, was considered the godfather of Texas modernism with his emphasis on natural materials, historic references, and warmth. He was virtually as unrecognized in state as he was out of it. His writings and speeches are compiled in the new book O’Neil Ford on Architecture, recently released by University of Texas Press and edited by Trinity University architectural historian Kathryn O’Rourke. Ford, who designed the 1974 expansion of what is now the Fort Worth Community Arts Center, was irascible and angry, and he was an advocate of architecture’s role as part of the larger fabric of urban life. But to him, civil rights, historic preservation, and architecture were in sync. He evoked history with every design, believing his projects could bring people together, even if they were for a tech giant like Texas Instruments’ semiconductor campus in Richardson. He is best known for his longtime affiliation with the private Trinity University in San Antonio, with structures linked to one another and sharing the hilly topography.

Dillon was much more like Johnson, in that he understood wealth was synonymous with development, or the lack of it, but Dillon recognized and advocated for reforming developers’ failures. He championed placemaking – just like Ford.

The three books may be about the singular work of different men, but each is also a history of the country’s transformation during the 20th century, a history that leads us to how we also politically arrived where we are today.

Thanks for the nice article Mr. Russell,

I believe that the iconic glass house is actually in New Canaan, CT, not Camden. theglasshouse.org continues to conduct tours there for visitors from around the world. If there is another house in Camden I’m not aware of it.

Thanks

Ken