Leaders from the city and Fort Worth police department recently took steps to present a friendlier, less militarized-looking budget for the Crime Control and Prevention District (CCPD) ahead of the passage of Fort Worth’s 2021 budget. Fort Worth formed its crime control district in 1995 in response to what the city said were high crime rates. The district is funded by a half-cent sales tax and adds around $80 million in discretionary funds to the police budget.

While violent crime across the country has fallen by more than 50% since the early 1990s, according to the Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization, Fort Worth’s CCPD budget has only grown since its creation. The 2021 CCPD budget is $86.5 million, according to the city. In response to a robust but unsuccessful campaign to vote down the CCPD this past July, Police Chief Ed Kraus said his department “would expand on some successful programs and create new opportunities.”

Specifically, Fort Worth police department is shifting SWAT and “enhanced enforcement” funding from the CCPD to the department’s regular budget while using the CCPD to expand the department’s crisis intervention team to handle situations that involve nonviolent individuals experiencing a mental health crisis. One new initiative, the Community Service Professional Program, consists of 10 civilians who will respond to nonemergency calls. Those steps, experts say, lower the risk of police shooting unarmed civilians while freeing officers to respond to actual crimes.

While Fort Worth’s CCPD became the target of public backlash this past summer following the murder of George Floyd, a Black man, at the hands of a white police officer, many Texas cities use crime control districts to supplement local law enforcement budgets with little to no controversy. What sets Fort Worth’s CCPD apart is the lack of independent oversight on how the $86.5 million in taxpayer funds are used.

“We are looking for applicants to sit on the CCPD board!” reads a message on the City of Argyle’s website. “Please click HERE for an application! Check Crime Control & Prevention District as the board type on the form.”

You can almost hear the Leslie Knope-levels of enthusiasm Argyle has for civic engagement. Haltom City, Southlake, Trophy Club — they all have independent oversight (non-police, non-elected official) of their CCPD budgets. Now, enter the Fort Worth Way.

In 2010, the Weekly covered the gutting of independent oversight of the city’s CCPD board (“Crime Control District Board Dissolved by City Council,” Feb. 2010).

“On Tuesday, the Fort Worth City Council voted unanimously to dissolve the 14-year Crime Control and Prevention District board and replace the appointed members with — who else? — themselves,” Staff Writer Betty Brink wrote at the time. “The move was being pushed by Mayor Mike Moncrief, according to Councilmember Joel Burns, who voted for the change.”

Moncrief, whose actions as mayor demonstrated that he was not a fan of transparency, accountability, or the Weekly, pushed for the disbandment of the independent board so CCPD funds could be used for shore up city budget shortfalls as needed, a CCPD board member said at the time. Fort Worth City Council has maintained absolute control over the CCPD since then.

Whether under the leadership of a Democratic mayor, as Moncrief was, or the city’s current Republican leader, Betsy Price, Fort Worth has long suffered from deliberate efforts to erode oversight and accountability on the part of our elected officials. Last December, City Council (with one no-vote from Ann Zadeh) gutted its ethics review commission and replaced it with a business-friendly sham of an oversight group (“Ethics Review? What Ethics Review?” Nov. 2019).

Placing city councilmembers in charge of the CCPD is fraught with ethical conflicts. As is common practice across the country, Fort Worth’s police union is a major donor in local elections. A cursory glance at recent campaign finance disclosures shows that the police union donated $15,000 to Price and Councilmember Cary Moon in 2019 and $17,000 (listed as “in-kind”) to Councilmember Carlos Flores in 2017 — and they are far from the only beneficiary of union funds.

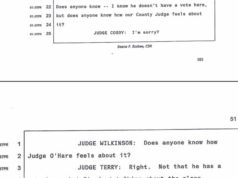

Recent CCPD board meetings last as few as 14 minutes and are held every three months, according to archived recordings. This past February, City Council voted to approve items on the CCPD agenda without discussion within the first minute (no joke) of the meeting.

“We have a motion to second,” Price said after calling the meeting to order. “Motion carries. I think you had a chance to look at the written report. No questions? We’ll move to staff presentations.”

Trusting city councilmembers whose political careers are partly bankrolled by Fort Worth’s police union to be good stewards of CCPD funds is naive at best, and many cities avoid those glaring conflicts of interest by seeking volunteer board members who represent taxpayers, not unions.

The 10-year-old power grab by Moncrief is part of a long list of dubious decisions made by the former oil-and-gas-loving mayor, but it shouldn’t shape our city’s present or its future. Fully one-third of voters recently opted to not renew the CCPD. A leading criticism of the district, according to numerous individuals from a wide swath of political persuasions, was the lack of independent oversight.

Placing citizens in charge of the district could go a long way toward rebuilding trust in law enforcement, and it could be a symbolic step away from Fort Worth’s long history of pandering to private business and union interests at the expense of transparency and accountability.

The Weekly welcomes submissions from all political persuasions. Please email Editor Anthony Mariani at anthony@fwweekly.com.