Charles Coger exhibits few characteristics of the homeless. The “young” 56-year-old North Carolina native is articulate and confident, and he rarely takes his eye from his listener. After serving in the U.S. Navy, he later worked for the U.S. Department of Defense, doing security in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Kuwait. He returned to North Carolina to work in law enforcement and security. Earlier this year, he came to Texas to take a job painting planes at DFW airport. The full-time work was rewarding, he said, and enjoyable, but this time also was when his life took a different direction.

“I let my anger get the best of me,” he said, “so I quit my job, and I became homeless.”

I came in contact with Coger after he emailed the Weekly asking for someone to look into the grim and, at times, disturbing environs of the Presbyterian Night Shelter (PNS), where he is a paying resident. In his message, he mentioned a shooting near grounds of the night shelter, which sits on Cypress Street near East Lancaster Avenue. It happened in May, killing one bystander, a resident, according to Coger. The shooter remains unknown, at least to Coger.

“I was watching the whole event,” he said. “It was a stray bullet as far as I could tell, nonintentional.”

Coger and I had agreed to meet one sultry Thursday morning last week. Driving east on Lancaster Avenue, it is difficult not to notice so many individuals utilizing the sidewalk as their home — men and women, young and old — along the avenue in such heat. Some are protected by the I-35 overpass, but others are simply sitting, some lying, in the sun along with what appear to be their worldly belongings, seemingly oblivious to the temperature.

Meeting in the lobby of the night shelter was not allowed, so we had prearranged with the nearby Union Gospel Mission to let us meet in its chapel. Coger entered through the Mission’s front door with three other individuals, a woman and two men, one of the men in a wheelchair. They had walked from the PNS to the Mission, with Coger pushing the wheelchair across the street, all wanting to share their experiences at the shelter.

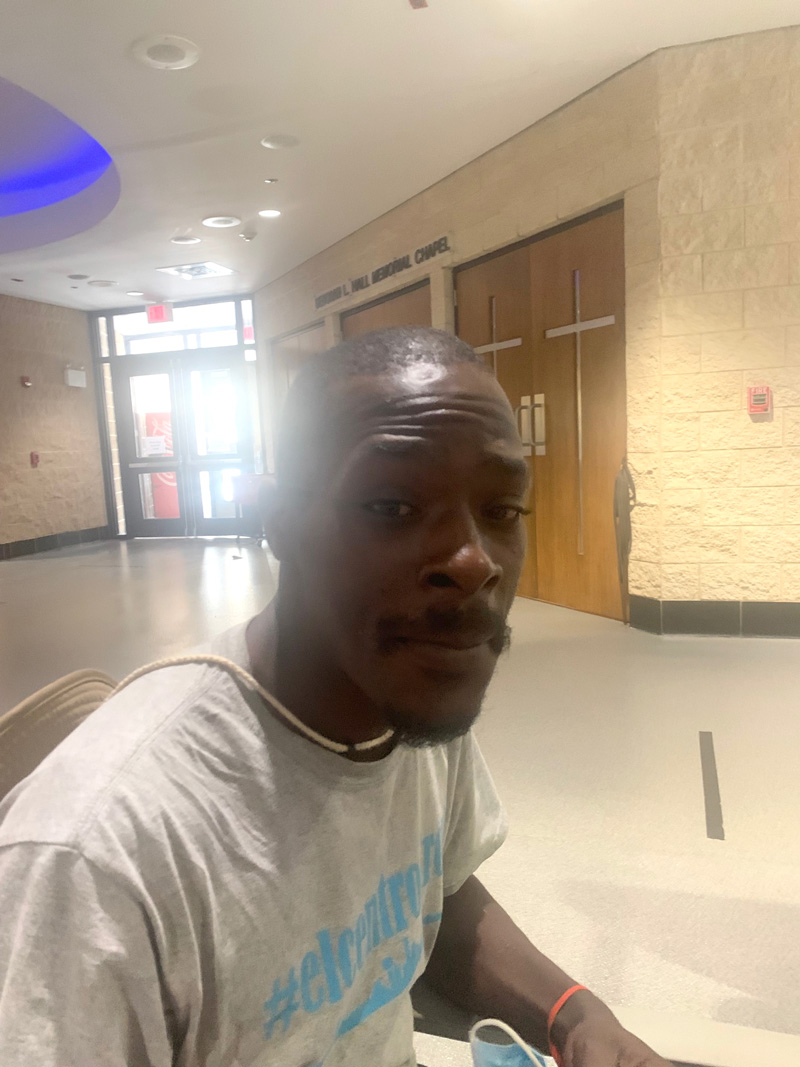

Eddie, 31, is from Mississippi and is also a veteran, having served in the U.S. Army. He currently works full-time in waste management, picking up brush in nearby White Settlement. The street is his home.

Photo by Linda Blackwell Simmons

“The shelter got rid of me,” he said. “Another guy and me got into an argument, but we cleared it up, or so I thought. But the staff didn’t think so. It’s cleaner on the street anyway. Mice run around in that shelter with no fear of humans. It’s like they say, ‘We live here, not you.’ I see roaches, I’ve seen a bug I couldn’t identify, people miss the toilets, but, mostly, it’s the staff. They have no de-escalation skills whatsoever. It’s like, ‘We got power over you. You do what I say.’ They got a state-of-the-art kitchen, but most of the lunches are sack, and most of them are peanut butter and jelly. I’ve seen ’em throw away food. Somebody needs to monitor the money that goes into this place. This has turned me off of Texas. Plus, I don’t like waking up with somebody in my face looking down at me.”

Eddie told of private citizens bringing food and clothing to Cypress Street who are harassed by PNS security. He believes the police are not the problem. “It’s the wannabe police that cause the problems.”

Susan, 54, is from Michigan originally but has been in Fort Worth for three months. She lived in Hereford when she first arrived in Texas but then moved to Fort Worth, where she at least had some family, but then she ended up at the shelter.

Photo by Linda Blackwell Simmons

“It’s horrible,” she said. “First day I was there, I was called an ‘old hag,’ ‘a piece of “s,” ’ especially by the young ones. I had my clothes stole while I slept. I’ve never been in the street, though. Yeah, there are those on drugs, prostitutes, but some people really do need help. The staff has their favorites, and if you are not on that list, you’re nothing to them. You learn that real quick.”

Susan added it is people like Charles who make it manageable. “We are like a family here, at least some of us. Some call me Mama Sue.”

Susan currently pays her shelter rent — $125 a month — from her social security check. Her goal is to obtain Section 8 housing and move on to a more independent life.

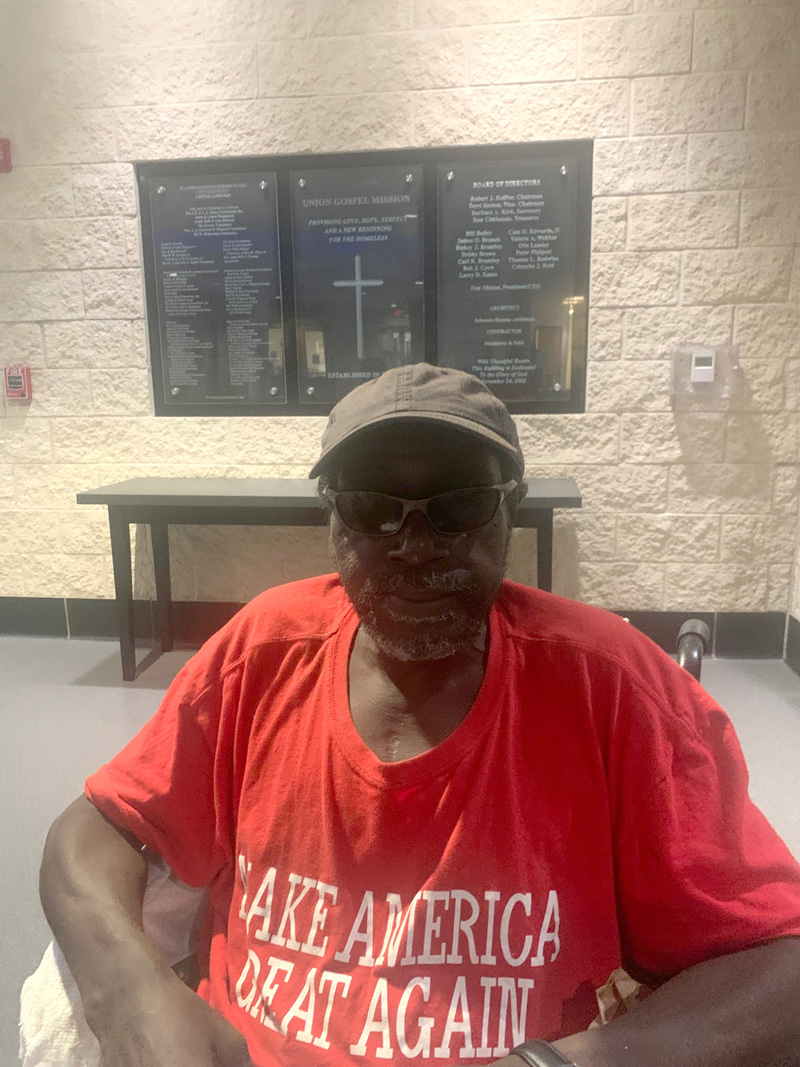

It was J.D, 61, who spoke next, not having said a word so far. He talked to me from his wheelchair with a blanket covering him from his waist down. From Philadelphia, he moved here with his wife when she became ill as she had family here. But then his wife died. His first stop was John Peter Smith Hospital (JPS).

Photo by Linda Blackwell Simmons

“They did right by me,” he said, “put me on medication, but at the shelter, if you say anything they don’t like, they kick you out. Doesn’t matter the color, the age, nothing. The rules are all so confusing, no consistency, no compassion. They contradict their own rules. You don’t know the rules from one day to the next. The staff has no skills. Women rule over the men, but the men staff are not allowed over the women. If you’re a resident, you eat. If you are not, you don’t eat. You’re on your own for food. I got kicked out. There are a lot of people who are just one paycheck away from being here.”

J.D. now sleeps on the street at night. I asked him how he moved from his chair to at least a reclining position on the ground. He mostly sleeps in his chair.

J.D. is unique in his situation. At the end of our conversation, I finally asked him about the blanket, as it was so hot that day. He keeps it because he has no feet.

“I just wanted to shed light on the situation,” Coger said. “I was raised to help my fellow man. We may be down but not out. Like Susan, I pay $125 a month to be considered a resident, and I have my own bunk. But we have to leave early and can’t come back until 4 p.m. Where do we go to the bathroom? I asked the attendant on shift. She didn’t know.”

Coger agrees with Eddie about the private security. On certain days, citizens, some sponsored by church groups, come to Cypress Street and offer food and prayer.

“One day I hear a security guy tell this couple they can’t give out food to the homeless because they leave trash everywhere,” Coger said. “If food is being handed out on a public street, what right do security officers for PNS have to stop food being passed out? There are rules for every little thing, and if you break them, you are put out. It’s run like a prison. I know because I worked in one years ago. They don’t care if you are blind, in a wheelchair, or have a mental illness. They kick you out, no warning. They bully the residents, no other word for it, talk to the residents like they are less than human. Some of the workers were homeless themselves. The female staff is the worst of all of them. There is no compassion from the staff. I do understand people can be hard to deal with, but if you can’t deal with the people, find another job.”

Coger applied to become part of the security at the PNS, but he was rejected. “One would think I would have been the perfect candidate. Staff is paid about $9 hourly, but security, I think, is about $14. I could have done a lot with that.”

Coger has his job back at DFW airport. He is now an airplane fueler rather than a painter. His goal is to rent an apartment in Irving to be closer to his job. His caseworker at the shelter, one who works only with vets, is assisting him. Coger speaks highly of him and says he seems to care.

Not one homeless individual with whom I spoke had a negative comment about the Fort Worth police.

“You respect them, they respect you,” Eddie said. “That’s all it takes.”

Commander Amy Ladd said approaching homelessness from a different perspective has been helpful. “About two years ago, we focused on ‘rethinking’ our police response to homelessness because traditional policing was not effective.”

The police created the Homeless Outreach Program and Enforcement (HOPE), a team that works with the homeless and mental health services to obtain better access to housing and other services. HOPE, she said, also strives to provide a proactive police presence to reduce violent crime and address the victimization that occurs in the homeless community. Ladd said the HOPE team has reduced violent crime in the East Lancaster area over the years and has connected many homeless people to jobs, housing, and services. To ensure Fort Worth police are practicing in the best possible way, Ladd said, HOPE partnered with the Tarrant County Homeless Coalition. Additionally, Fort Worth PD has been selected to participate in a study in policing and homelessness with the University of Texas at Arlington.

It is only fair to appreciate that the work of the PNS is difficult. The management and staff confront harrowing situations every single day. Rules are necessary and may seem harsh to an outsider. Individuals many times bring their own agonizing and heartbreaking histories with them — the safety net provided sometimes precarious and tenuous. With rotating groups coming and going, hygiene is a problem. I made a number of attempts to obtain comment and a better understanding of why certain actions are taken at PNS, why certain rules are at times so severe and inconsistent, and how clients with disabilities are evicted so readily. My attempts were made by phone and email and at various times of the day, but no response was received from shelter representatives.

Coger closed our meeting that day. He is the first to say this is not about him — he has hope and confidence that his homeless time is limited. It is about his compassion for the friends he made during the short time spent in near Eastside Fort Worth.

Rita skeeter of Fort Worth everyone. This isn’t journalism it’s salacious, unsubstantiated gossip. Do better Fort Worth weekly

Genevieve, it sounds like the reporter spoke directly with the affected parties and reported accordingly.

Once again another article about the BS at PNS.

It goes straight to the top there the director is a sniveling little screamer, think Hitler in the Bunker videos. Saw him get in a yelling match with someone and then just turned to tell the guard next to him to “find a reason” to pepper spray him then they tackled him afterward and told the cops he hit them first. I had to dodge the pepperspray I was the next person in line.

And yes they will chase anyone handing out food out of the neighborhood they aren’t even on PNS property or even in front of the buildings on public streets.

The director told anyone who has an issue with him to write their name down. He then kicked everyone of them out for the night for being “argumentative”. He was the one screaming and cursing because they were refusing to let anyone into the shelter for hours and people who needed to get ready for work were upset. They do things like this and make up a reason like the streets are dirty or theyre cleaning to kick people out after they have gotten their money for the month when they get worried people may gang up in the staff ans complain or publicize stuff there.

You should have seen the shelter try and cover up the shooting. Wouldn’t tell anyone anything and were trying to kick people out left and right because they were afraid of lawsuits or people banding together. They did the same thing when Covid broke out this summer in the women’s dorms they refused to let anyone even get food or water without a bag of trash as currency and kicked most people out on false allegations because the feared negative publicity.