Big hair, turned-up collars, Members Only jackets, Swatches, New Kids on the Block. There were gobs of ridiculousness in the 1980s. Too much to list really.

It wasn’t all totally awesome. In fact, in many ways it was unequivocally absurd.

Over the last century, seven decades were defined by war. Another two were given meaning by Prohibition or a great depression. The 1980s were the only decade in the last 10 that wasn’t defined by any of the three — unless you count the War on Drugs, which was initiated by Richard Nixon in 1971 but more infamously waged by Nancy Reagan’s “Just Say No” campaign. But no one took that seriously (especially the CIA). The most traumatic thing that happened in the ’80s was probably New Coke. The rising generations of the other nine decades had the crux of their angst defined for them. We were left to our own devices.

Our elders called us Generation X or Gen X, and there was something to this. In algebraic terms, we were an unknown quantity. We seemed directionless, ambitionless. Without a war or cataclysmic social or economic fiasco to suffer through or rail against, we had the luxury of looking around and taking note of things. Usually superficially but still. There was no movement or spirit-crushing calamity to sway us from what was right in front of us. It was a blessing and a curse.

For those of us who were paying attention, there was this incredible sense that everything was wrong or going wrong. Not one thing or one issue. But everything.

Capitalism, corporatism, Reagan, famine, AIDS, ozone depletion — Holden Caufield was only a third right. The world of adults wasn’t just phony. It was irresponsible and dangerous. The world faced a thousand reckonings, none of which were our doing, and we deeply resented the inherited, irretrievable missteps, the resultant, impending disasters, and the day the bill for the causative idiocy and irresponsibility would come due. It seemed a long way off, but it wasn’t. And the extraordinary, horrifying question that occurred to us even then was what we would do when we were adults.

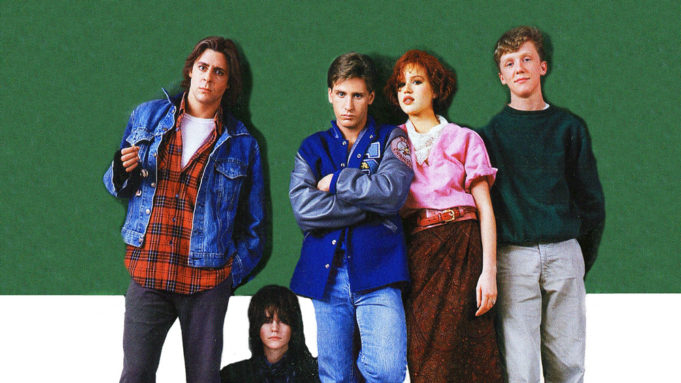

In The Breakfast Club (1985), the most popular cinematic examination of Gen X during this period, every high school participant’s stint in detention was due to some form of parental obliviousness, neglect, or specific parentally encouraged oafishness. And after each kid shares their reason for being there, Emilio Estevez’s character honestly and poignantly says, “My god, are we gonna be like our parents?”

Now, for the adults and grownups of the period who observed our generation from without, pay special attention. No matter how knuckleheaded or peabrained any of us may have seemed at the time, all of our ears perked up at the Emilio character’s interrogative. And what followed.

Molly Ringwald’s character says, “Not me. Ever.”

Not me. Ever.

Then Ally Sheedy’s character breaks the spell with a statement most of us resented (in every cell of our being): “It’s unavoidable. It just happens. When you grow up, your heart dies.”

This is how the real world appeared to us. And our parents’ recipe for success and personal fulfillment was following in their heartless footsteps.

We were the first generation raised on video games and arguably the first generation of kids relentlessly subjected to corporate marketing strategies designed to make us complacent little materialists. To those of us who withstood these campaigns with some semblance of sentience intact, the “real” world (as our elders put it) was compromise, a Big Sellout. Adulthood was anathema. And the rat race was a shameless, voluntary evil.

No one stated our distaste for Capitalism more succinctly or humorously than John Cusack’s character in another ’80s classic, Say Anything (1989). When asked by his romantic interest’s father what he planned to do after high school, he speculates candidly, “I don’t want to sell anything, buy anything, or process anything as a career. I don’t want to sell anything bought or processed or buy anything sold or processed or process anything sold, bought, or processed or repair anything sold, bought, or processed.”

Amen, brother.

Or at least that’s what our sentiment was then.

Somewhere along the way, however, we forgot. Or, as our well-meaning parents put it, we “grew up.”

It was a lie then, and it’s a lie now.

Decent, reasonable adults don’t disenfranchise their neighbors for political gain. Fair-minded folks don’t sell out fellow citizens for higher profit margins or inflated stock options. Practical-minded grownups don’t sacrifice their children’s future well-being for shallow, short-term gratifications. And responsible, rational human beings don’t base their economy on gambled derivatives, resource speculation, or opportunistic wars to keep Big Oil — and the biggest consumer of oil and gas on the planet, the U.S. military-industrial complex — chugging forward and belching death.

Americans haven’t been adults about anything for years, but perhaps the closest we came to it was in the ’80s when Gen Xers looked around and said, “Wow. This is fucked up.”

The revelation was drilled out of us in short order.

Love him or hate him, Barack Obama was the first Gen-X president, and he brought a mild version of this sensibility to the job. He moved the dial a little, but he was followed by a rabidly backward Baby Boomer and then his own former vice president, a tepidly middle-of-the-road Boomer dealing with a stupefyingly divisive pandemic.

Now, of course, we’re the “grownups.”

And we have become our parents. We’re buying and selling and processing lies, staunching our idealism, dooming our children’s future, and defiling the fierce, innocent soul of our generation. If our hearts aren’t dead, they’re dying. We willfully embrace falsehoods and invest in them. So much so that we can longer make sense of our lives outside the careful confines of ignorance and wishful prevarication.

As teenagers, we weren’t impressed. As adults we’re not impressive.

It’s too bad.

We had such promise. — E. R. Bills

Fort Worth native E. R. Bills is the author of Fear and Loathing in the Lone Star State, Texas Oblivion: Mysterious Disappearances, Escapes and Cover-Ups, and The 1910 Slocum Massacre: An Act of Genocide in East Texas.

This column reflects the opinions of the author and not necessarily the Fort Worth Weekly. To submit a column, please email Editor Anthony Mariani at anthony@fwweekly.com. Submissions will be edited for factuality and clarity.