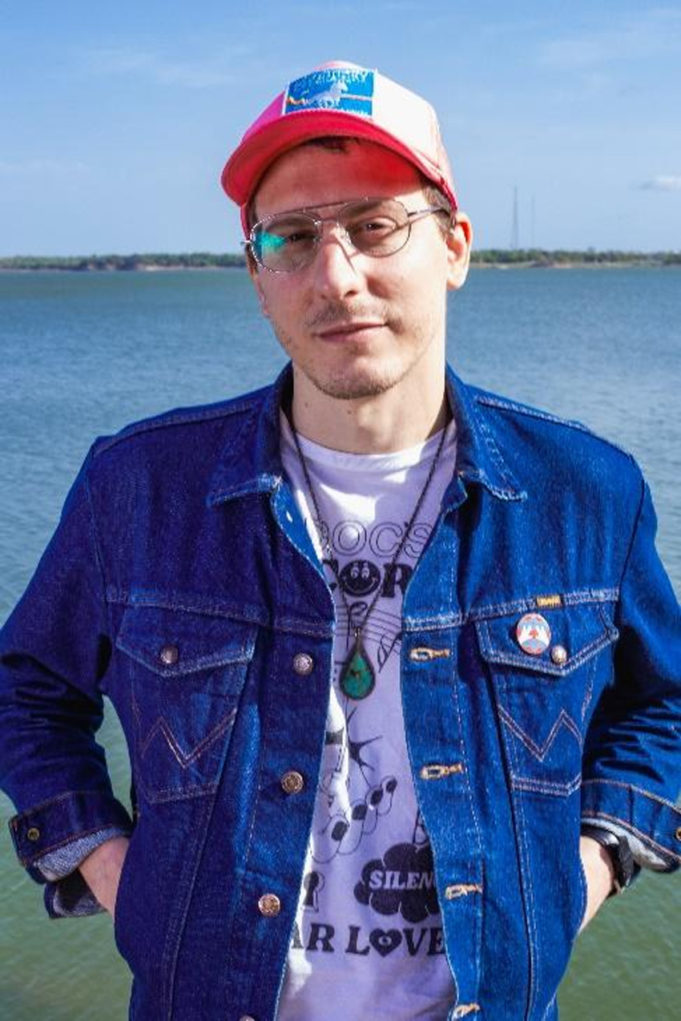

In early summer of 2020, singer-songwriter Cameron Smith was approached by local artist and friend Jeremy Joel about providing some music for a documentary film Joel was wanting to make about S.A.M. (Support a Motherfucker) Gallery, Joel’s small, underground, outsider arthouse. Smith was more than happy to oblige. Tragically, Joel would be reported missing just days later, ultimately being discovered to have died at just 37 years old. Though, as it stands, no such film is now likely to be made, Smith nevertheless continued writing with that unfulfilled project in mind. Two years later, the fruits of that inspiration have become Smith’s sophomore solo album, Shine.

Original artwork by Jeremy Joel

“Some of the songs had already been written when [Joel] hit me up about doing the music for this movie,” Smith recalled. “I had started by trying to flesh one of them out. I don’t remember which, but something for that idea. Then, when he passed away, I just started writing for what that movie would have been in my head, I guess.”

The 10 tracks on Shine feel like the next step in a natural progression of Smith’s writing and cement a developing maturity that seems well-honed and confident as well as it does intimate and contemplative. Highlighting Smith’s lyrical acumen, the tracks are presented simply, unbothered by slick production or lush instrumentation, yet with a fullness achieved by other means. There’s a seeming ease to his verses, which weave stories of nostalgia, growth, loss, and a tranquil hominess to the sonic textures that wrap around the listener as comforting as a plump down blanket. A large part of these textures is owed to a newfound collaboration for Smith.

As he was developing the songs that would become Shine, he sent demos to friend and fellow singer-songwriter Eric Osbourne for his opinion. During the depth of the COVID lockdown with unusually expendable time, eventually, Osbourne started sending the tracks back with additions he had made of little parts that he heard in his head and which he felt might work. Receiving them, Smith would employ some, change some, write on top of others, cut some, and send them back. Then the process would start again. This unintentional pseudo-partnership transpired back and forth for a bit before the two realized they were subconsciously actually working on a record together.

“The songs would have, like, a robot drum beat on it, and I’d add a little lead part, or melodica, or saw, whatever kind of things,” Smith said, “and [Osbourne] would take it and augment that or add a vocal harmony or something new. Though they’re my songs, we really developed the atmosphere of them together.”

Neither Smith nor Osbourne recalls the collaboration as intentional. At least, not initially.

“I think it was just quarantine, and we were sort of becoming better friends and talking about lots of music,” Osbourne said. “I think it was kind of an accident really that we took it as far as we did. We just go into it. It’s like [Smith] sent me a bunch of skeletons, and I threw some meat on the bones or something.”

Using the BandLab app, the two passed the tracks back and forth, with much of the recording devices simply being their iPhones, an unintentional means that adds to the record’s charm.

“Eventually, I started to realize that this is becoming a thing, and I don’t want to take it and re-record it somewhere,” Smith said about the recordings he first assumed to be simply demos. “I like it the way it is. The character started to match this certain aesthetic, like [Joel’s] street art, sort of like painting over things. There’s an element of mixing mediums, and layering things, and erasing things, and building off that.”

The lack of studio sheen lends Shine something different — an aesthetic of intimacy that a running clock in an expensive tracking room just couldn’t duplicate.

“It’s really like creating this sonic room that you can step into and visit a place,” Smith said of the sound. “It’s like a sonic gallery. You’re building an actual space that you want people to feel invited into.”

Osbourne agrees with these motivations.

“It’s not, ‘How do you want the song to sound?,’ ” he explained, “It’s ‘How do you want the room you’re in to feel?’ ”

With self-reflective tracks like “Time in Reverse” or the tender ode to late Silver Jews/Purple Mountains frontman David Berman, “Song for David,” or the watery slide of “Swimming in the Wind” and the stark beauty of “Wildfires,” the album’s title track, Shine, is another leap for Smith as an artist. The last few years have seen exponential growth for him as a songwriter, and this is simply the latest peak scaled by the ever-prolific songsmith. From his days fronting witty garage-punks War Party to the erudite lyrical stylings employed with his current full band, Sur Duda, to the intimate folk-nouveau of his solo work, songcraft has become an obsession for him, and the tendrils of that obsession now reach deep into the tissues of his material, providing the rich bloodflow that gives them life. There’s a comfort with the art he’s now obtaining, but he’s not settling in. Instead, he keeps pushing.

“I feel like I’m just at the beginning of becoming what or whoever I am” as a songwriter, he said. “I once heard someone say that your job as an artist is to remain inspired. For me, the work in and of itself is inspiring. I never want to feel like I’m done working.”

Thank you for your thoughtful coverage 🙏