Growing up a pro football fan in the Metroplex was magical in the ’90s. The Dallas Cowboys were the platinum standard for gridiron excellence, and Warren Moon’s Houston Oilers — though oft mediocre — offered a fun alternative if you were bored of America’s Team winning all the time. College football was the opposite. SMU was in postmortem reconstruction from the NCAA’s death penalty, and TCU was middling bordering on irrelevant. I sported a white Emmitt Smith and blue Troy Aikman jersey on alternating days — can’t even recall another article of clothing from 1991 to 1994.

Then something happened the Cowboys never seemed to recover from: the salary cap. The collective bargaining agreement would successfully keep more money in NFL owners’ pockets and try to temper the domination of just a few teams. Shortly after, the Frogs and Mustangs found themselves excluded from the Big 12 after the formerly prominent Southwest Conference disbanded in 1995. TCU and SMU dropped to mid-major status in the Western Athletics Conference (WAC), an all-too-appropriate name for their new station.

For the next 25 years, the professional and collegiate games mirrored similar financial restrictions and careful resource management. Sure, athletes found ways to make money at university, but it was always don’t ask/don’t tell. The jaw-dropping spending came in the form of the arms race of athletic facilities to attract the best recruits. Now, it’s all basically for naught. House v. NCAA now says colleges can revenue-share more than $20 million per year with their athletes. Alongside what amount to venture-capital funds for Name, Image, and Likeness (NIL), we’ve entered what could be considered the college football cold war — outspend your enemy, even if you never fire a single shot.

Rankings and projections are starting and, rightfully so, are influenced by what each school is shelling out for their roster, which for most teams is shifting substantially every season. No longer do pundits and analysts have any earthly idea how good a team will be. They never really did (except yours truly, of course). But the incredible shifting of rosters and money-bombing of top recruits have turned collegiate football into a race of which school can shovel money into the fire the quickest.

What will teams achieve for this incredible expense? Well, that remains to be seen. My instinct says not much. Previously, the big money was levied at high-profile coaches and eye-popping facilities. Almost every competitive college boasts weight and recovery rooms that would make most Olympic training centers seem like prison yards, but most schools have not turned former winning into current success. Texas A&M comes to mind. Only two years ago, the Ags paid former coach Jimbo Fisher almost $78 million to seek employment elsewhere. The College Stationites spend as much or more than any other program and don’t have any hardware to show for it.

Currently, the Big 12 team to watch is Texas Tech, whose NIL collective is one of the most aggressive and well-funded in the country. The Matador Club paid NiJaree Canady — one of the best softball pitchers in the country — $1 million to transfer from Stanford (the largest NIL deal for a college softball player — ever) and turned the acquisition into a College Softball World Series appearance. Current estimates are that Tech will pay their footballers around $28 million this season, and their preseason ranking (23) is a reflection of that.

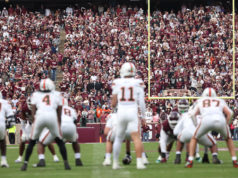

Locally, the Tennessee Volunteers attempted to lure TCU’s starting quarterback Josh Hoover from Fort Worth during the offseason. Hoover, who reportedly makes more than $1 million with the Frogs, turned down an offer from the Rocky Toppers for at least an additional million. And the Texas Longhorns are ranked No. 1 in the preseason poll, anticipating a roster spend between $35-40 million.

My most pressing concern is how this all feels, which can only be described properly as “ick.” I was fairly transparent that I thought college athletes should be entitled to compensation since their bodies and careers are the ones on the line, but players taking pay cuts on rookie contracts in the NFL just feels wrong. Combine that with the proliferation of players transferring en masse every single year, and the game is but a shadow from the early aughts, when there was still a tacit suggestion that these athletes were cosplaying as students and peers to their universities’ nonathletes in some way. It all gives a third-marriage vibe. The passion might be there somewhere, but it’s an afterthought compared to retirement accounts and liquid assets.

So far, NIL doesn’t seem to have affected on-field results in any concrete way. Teams that have been dominant still are, and the normal flux of teams on the precipice midseason, as well as the occasional surprise, seems within the margin of error to which we’ve become accustomed as fans. You can wager with good conscience that teams won’t find the level of success by simply paying more for players that Red Raider softball enjoyed with their pitching acquisition last season. Football is simply too complex and dynamic a game for one player, or even a group of players, to make that kind of a difference. Sure, there are outstanding game changers, but supporting pieces and coaching schemes make a more substantial difference in football than in other sports. You need look no further than the NFL to see teams completely whiff on draft picks and pay huge extensions to players that amount to no more wins than previous average seasons. There are simply too many factors to accurately predict how a team and their dynamic will evolve simply based on how that athlete played in a different season, on another team, or at a different level. In many ways, offering huge money — especially to high school players — might be the worst investment college football programs can make, but, hey, my portfolio is still half GameStop, so what do I know?