Cowboy Noire opened at 400h Gallery & Studio in Sundance Square a little over a week ago, and if you’ve lived in the city long enough, 400h is in the same spot as the old Whataburger, next to where the old Coffee Haus used to be, on Houston Street.

Over the past three decades, the look and feel of downtown Fort Worth has changed with Sundance Square at the helm, defining that look for the bulk of the city square. This is no longer Hell’s Half Acre, where Butch Cassidy, the Sundance Kid, and Wyatt Earp once roamed, or the thriving nightlife spot of the 1990s, when you could hear icons of jazz like Fort Worth’s own Ornette Coleman and Dewey Redman, or the sounds of Herbie Hancock, Run DMC, or Camp Lo right in the middle of our (then) small city. Yet it is fitting that 400h is the site of an exhibition that seeks to reflect the fuller story of cowboys of the American West, a story that includes the integral contributions and presence of Black cowboys.

“Black cowboys were the original cowboys,” writes curator Kelsha Reese in a statement, “shaping the skills, style, labor, and culture of what it means to labor and care for the land and the animals that live on it.”

Reese goes on to say the show also has the goal of “challenging the erasure of Black presence in cowboy culture and reclaiming a history that has been rewritten and overlooked.”

Photo By Christopher Blay

Nowhere else in Fort Worth is that history being preserved better than at organizations such as the National Multicultural Western Heritage Museum (founded 2001). Founder James N. Austin Jr. and their historians carry out a mission to educate visitors about the history of the forgotten cowboys, not only the Black ones but ones from the First Nations, Mexico, and Asia, and examine their role in the development of the American West. Beyond exhibitions and film, the organization’s two annual rodeos — one during the Fort Worth Stock Show & Rodeo on Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday, the other on the National Day of the American Cowboy (the fourth Saturday in July) — put that history in full view and in context.

My own introduction to cowboys came from watching Westerns at movie theaters as a child. Wide expanses of desert vistas shot in Cinemascope wowed a little kid growing up in Monrovia, Liberia. Men on horses with shining spurs and big guns rode across the screen during shootouts with “Indians” and outlaws in the plains and deserts of the American West.

I don’t think I saw any depiction of Black cowboys until my early teens, when I moved to Texas from Liberia, and even then, their presence seemed like an anomaly. (Mel Brooks’ Blazing Saddles comes to mind.) It wasn’t until the early 1990s with movies such as Posse (1993), Rosewood (1997), and Netflix’s The Harder They Fall (2021) that movies featuring Black cowboys could be numbered in the double digits. These stories, plus documentaries, including Jordan Peale’s High Horse: The Black Cowboy, bookend Black cowboy history and are the perfect compendium to Cowboy Noire. I point to movies because of their role in popular culture. Even fictionalized versions of real-life cowboys move the needle in the right direction, toward what Reese describes as “the true story of the American cowboy.”

Photo By Christopher Blay

Featuring the work of 25 artists across Texas, Cowboy Noire includes some familiar names, many of whom know one another and have exhibited together. That camaraderie shows up in the assorted paintings, photographs, and sculptures, making for an unexpectedly vibrant and diverse exhibit.

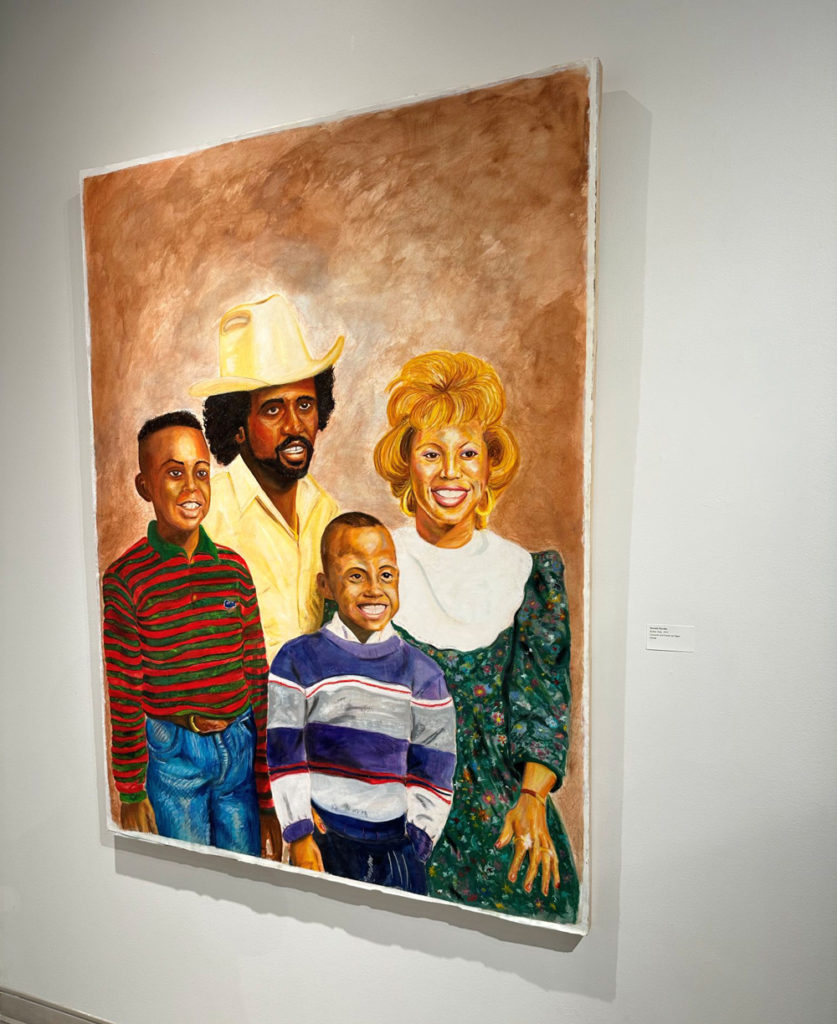

“Bubba Nem” probably held my attention the longest. Derrick Hardin’s drawing is an endearing portrait that reads as a classic Olan Mills or Sears composition from the ’90s, complete with period hairstyles and clothing. Although your gaze is not directly met by the figures in the monumental piece, standing in front of the work still conveys a deep and personal sense of family, culture, and community. The style is unmistakably Western, with blue jeans, a big belt buckle, a cowboy hat, and a ruffled collar to boot. I really love this drawing for the iconic “tells” of photos you could find in the homes of Black folks of a certain generation. Perhaps that is why I am so drawn to it and why it resonates so much with me.

Another standout piece, “The Goat Myself” recalls the regional verité painting style popularized by Texas artists such as El Franco Lee II in Houston and Brandon Thompson in Dallas, or what the hip-hop outfit Outkast would call “da art of storytellin’.” Kameron Walker’s tableau has rich warm tones and is overflowing with bravado and symbolism, a black panther here, a tiger there, and goats everywhere. It is a deftly painted work that is both powerful and expressive, the kind of painting that makes you want to enter the canvas and be a part of that scene.

Photo By Christopher Blay

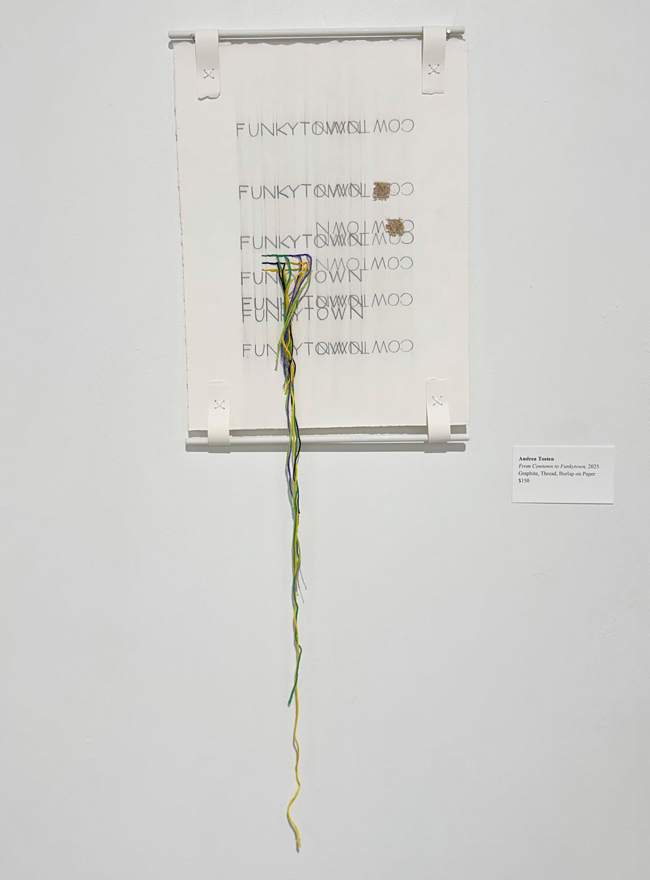

Perhaps my favorite work in the show is its most unconventional foray into cowboy life and Fort Worth cultural identity. Andrea Tosten’s conceptual drawing “From Cowtown to Funkytown” combines materiality steeped in Black craft technology with her keen knowledge of art history and cultural awareness. It is an understated work in an otherwise vibrant show, and if you move too quickly through the exhibition, you might miss it on the north-facing wall. In the drawing, the words “Cowtown” and “Funkytown” overlap where they meet in the middle at “town,” which seems to emphasize the feel of Fort Worth — despite its cosmopolitan ambitions and the fact that we are the 10th-largest city in population in these United States. Of course, the clash of cultures is also evident in how we keep it real here with cowboy culture (Stockyards, anyone?) and more than a little bit of funk (see: Leon Bridges, Walter Scott of The Whispers, and Sly Stone, originally from Denton, but we’ll claim him).

Tosten’s work and the others in Cowboy Noire make for a celebration of culture and a testament to perseverance. We are our ancestors’ dreams that cannot be erased or edited out of history (nor relegated to February). We are the caretakers of culture, and there are too many of us in whose lives these stories and this history continue through and through for it to ever fade away. Artists here — Charles Gray, Dontrius Williams, Tatyana Alanis, Cedric Ingram, Assandre Jean Baptiste, and all the rest — are good stewards of the culture, and it thrives in this collective of emerging and established Black Texas talent. Now, rustle up some friends and family, and go see this show.

Cowboy Noire

Thru Mar 22 at 400h Gallery, 400 Houston St, Fort Worth. Free. • Artist Talk 3-4pm Sat, Feb 21. Free. 817-266-3216.