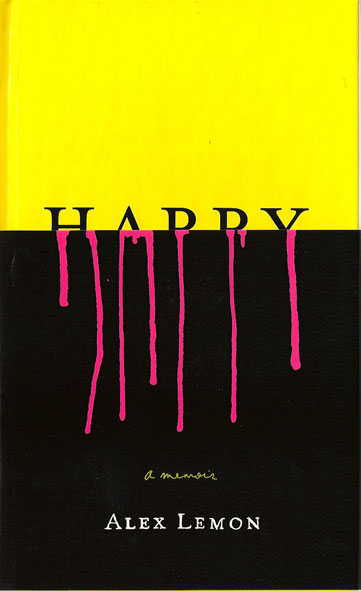

Titled after his college nickname, Alex Lemon’s Happy is another in a slew of memoirs in the vein of Boy Meets Obstacle, Boy Overcomes Obstacle, Boy Finds Redemption. Typically in such books, a self-destructive young man — almost every hot new memoir today is by a young man — is thrown into exigent circumstances that force him to confront the selfish asshole in the mirror.

In the largely fictional A Million Little Pieces, memoirist/novelist James Frey must dig himself out from beneath an avalanche of drugs. In Running with Scissors, Augusten Burroughs is crippled by a dysfunctional family. In Happy, a tiny book set during the Clinton administration and mostly on the campus of Macalaster College in St. Paul, Minn., the narrator must deal with a bleeding tumor on his brain stem. Happy, a star catcher on the baseball team and first-team All-American bon vivant, handles the situation the way any other wild-eyed small-college athlete would: He parties his ass off before surgery.

The book opens with a painfully glorious description of a hangover — or possibly, as the reader will later realize, a case of vertigo brought on by the bleeding in the narrator’s brain. Happy says, “I must have drunk a bottle of Drano last night, snorted a bag of glass, and leapt open-armed from the top of the stairs. A tree. A roof. The moon.”

Happy knows his way around a bong and a beer bottle. He also somehow manages to attract gorgeous, lovely girlfriends but can’t keep himself from cheating on them. Until he really needs his sweet Ma, the one person in the world who represents pure, unadulterated, unconditional love and who thinks more highly of him than he does, he sweetly rejects and ignores her. Happy, basically, is a tool. Or douchebag. Or whatever other pejorative moniker nowadays applies to male college students whose tangible though suppressed fear of adulthood instructs them to booze ’til oblivion, objectify women, and focus almost uniformly on themselves. Even total bros might find themselves rooting for Happy’s comeuppance.

The main character also doesn’t have the good literary fortune of speaking on behalf of a slighted minority. He is not a descendant of slaves. He is not a Holocaust survivor. No, he’s just a young, white, virile, spoiled male whose childhood, by all accounts, was also comfortable. Even Happy’s scars are beautiful, the noble byproducts of valiant — valiant — battles fought and lost: against self-loathing, against alcoholism, against genetics. Otherwise, Happy is flawless. He has no inherently repugnant faults. He is not a chronic masturbator. He is not a petty thief. He is not a kiddie fiddler. The worst that Lemon says about Happy arrives on page 182 of 304 pages of large typeface and wide margins: Happy is a shitty basketball player.

The story’s juice comes almost solely from the main character’s dire situation — even the hardest hearts among us are bound to feel sympathetic toward Happy, a young adult in his prime smacked down by a random life-threatening illness. A little more juice comes from Happy’s somewhat cast-off recollections of being molested as a child by an older cousin. They’re there clearly to make Happy a more likable character. (They’re also probably there for the author’s sake. Writing about demons goes a long way toward destroying them. The memoir genre is the perfect forum for anyone wanting to get dark matter off his or her chest.)

Happy becomes a passable human being toward the end, when he finally begins to realize the awesomeness of his interminably caring and powerful mother, who helps nurse him back to health, physically and emotionally. He doesn’t begin to respond to her in the loving ways in which she always reached out to him. He stays true to himself and celebrates her on his own distinctly dude-ish terms. Back in his hospital room after he has taken his first post-op steps on a walker, he gushes to her, ” ‘That was pretty awesome, huh? Aren’t you glad I spent so much time in the gym instead of doing my chores? … I know you’re going to start pumping iron now. Get all big, aren’t you, Ma? Oh yeeeaaaaah!!!’ “

Getting to Happy’s redemption isn’t hard. The narrative is extremely propulsive, thanks in no small part to Lemon’s lush writing style. A professional poet tackling his first long-form assignment, the 30-year-old author luxuriates in coloratura. He employs evocative language that conjures up Tom Wolfe and Hunter S. Thompson but never devolves into imitation. “I’m swallowing myself alive,” Lemon writes in one of the book’s most precise, colorful passages. “Happy’s Hallowed Eve brumbles into Weeks of Pleasing Myself. I celebrate the ticking seconds of every goddamn day. I’m a festival, a parade, and the drinks are vicious. There is cake and blood-slick flesh. These are the Nights of Atoning for Nothing, Star-Pied Afternoons.”

One of Lemon’s cleverest lit-tricks is to use nouns as verbs: “We sardine into the circle of people,” “I Chinese-dragon down the middle of the road,” “her face puddings,” “shipping tankers domino the hem of the water,” “the party cords around the basement.” Strict grammarians and John Updike devotees might disagree, but Lemon’s verbal legerdemain works more often than not.

Lemon’s characterizations of his friends, though, are mostly shallow, mere accumulations of dialogue — bad dialogue. But it’s not entirely Lemon’s fault. That slang-laden, cussed-up, profane way of communicating among boys is inherently artificial. It’s emotional armor. By defining his friends’ meaning in his world, Lemon might have helped keep them from simply lying there no deeper than the page upon which they appear. Even the dialogue between Happy and his two best friends, Casey and Brown, boils down to small talk, which doesn’t help engender the kind of sympathy from the reader that is necessary to entirely redeem ol’ fucked-up Happy.

Abjection to redemption is both a universal theme and saving grace in memoirs, and it’s what ultimately redeems Lemon’s breezy memoir. Gratuitous, merely shocking memoirs can be classified as boring victim art. Good memoirs, however, like Happy, qualify as Art-with-a-capital-A.

Happy: A Memoir

By Alex Lemon

Scribner

304 pps.

$25

Alex Lemon book signing

6:30 p.m. Thu, Jan 28, at TCU Barnes & Noble,

817-257-7844.