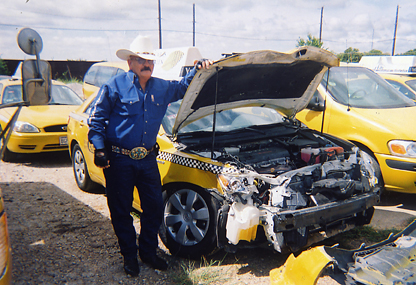

When veteran cab driver Robert Spence stepped into his bright yellow taxicab on a summer morning a little more than a year ago, it barely had a scratch on it.

The car was a brand new Toyota Camry Hybrid that Spence had begun leasing from Yellow Cab only months earlier. He had worked as a taxicab driver for 32 years and was glad to have a new one — it had no dings, no accidents, not even another driver.

The car was a brand new Toyota Camry Hybrid that Spence had begun leasing from Yellow Cab only months earlier. He had worked as a taxicab driver for 32 years and was glad to have a new one — it had no dings, no accidents, not even another driver.

Spence was on his way to pick up a customer when a red Chevy pickup sped through a stoplight at South Main and Pennsylvania streets. As the cars crashed into each other, Spence’s shoulder seat belt malfunctioned and the airbags failed to deploy, allowing him to hurtle forward into the steering wheel and the cab’s dispatch computer.

The truck driver received tickets for failing to yield and running a light. Spence, according to doctors at the hospital, received brain damage, ruptured discs in his neck and back, and a possible contusion to the heart. The cab was totaled.

“I’m just grateful that I didn’t have nobody in the car with me,” Spence said. “It’s more than likely the customer would have been hurt worse.”

For Spence, who has since sued Yellow Cab, the wreck and its aftermath brought home dramatically the seriousness of his concerns about the safety of local cabs, as a result of cab company practices and what he believes is lax regulation of the industry.

He and other drivers believe that vehicle inspections — by the city, the state, and cab companies themselves — are inadequate and not only because they ignore airbags almost entirely. They report that cab companies frequently put damaged cabs back on the street without making full repairs. And they worry that many drivers work far too long — up to 18 hours at a stretch, sometimes with only a couple of hours in between shifts, which violates a city ordinance limiting cabbies to a maximum of 12 hours per day.

City records don’t contradict many of their accusations. In responding to an open-records request by Fort Worth Weekly, city officials did not produce a single document showing that the city has removed a Yellow Cab taxi from service in the last four years for failing to meet “the minimum standards for appearance, condition, age or equipment,” as stated in the city ordinance.

City ordinance also requires that any time a taxicab is in an accident, the company must send the city a sworn affidavit within five days, affirming that the vehicle has either been repaired or removed from service. The city produced no such affidavits for the last four years. Nor did officials provide any documents showing that drivers are ever asked about their work hours or that the city takes any other action to enforce the 12-hour maximum.

Gerald Taylor, the city’s Ground Transportation Coordinator, is responsible for inspecting all taxicabs that operate within Fort Worth. After a brief interview with the Weekly, he declined to answer subsequent questions. City officials did not respond to questions about the missing documents.

Spence sought compensation for his medical bills from the company that runs Yellow Cab in North Texas. When the company turned him down, he sued it for negligence, and the suit is still pending. Spence said that when he spoke to Taylor several months after his accident, the city transportation coordinator said the company had never notified the city about the wreck.

The former cabbie is also a party to a second lawsuit, a class action alleging that Yellow Cab misclassified hundreds of drivers as independent contractors instead of employees, which would make the company liable for years of unpaid wages.

Jack Blewey, president of Yellow Cab in North Texas, said that any complaints about the safety of the vehicles are the result of discontented drivers who no longer work for the company.

“I don’t put a car on the street that’s not safe,” Blewey said. “I can guarantee there’s no driver for Yellow Cab who doesn’t think we inspect.”

Several drivers, including Spence, said cabbies and passengers have been injured partly as a result of unsafe vehicles.

In the Metroplex, the Yellow Cab franchise is operated by Irving Holdings Inc., which controls the majority of the taxicab market for the Dallas-Fort Worth area. As much as 95 percent of requests for taxicab service come to Yellow Cab, according to Blewey.

As the largest cab company in the area, it faces plenty of personal injury claims. From June 2004 through 2007, Yellow Cab paid nearly $4 million in claims, based on more than 150 claims per year. One lawsuit still in legal limbo asks for a verdict in excess of $1 million.

“That’s a lot of carnage,” said Bob Haslam, a Fort Worth attorney who specializes in personal injury.

Blewey said there is no connection between inspections and injuries that happen to passengers or drivers in the company’s cabs.

“Cars get turned down all the time by the inspections,” he said. “We’re taking bad cars off the street because we don’t want the liability.”

The city requires Taylor to inspect the taxicabs twice a year. According to Taylor, each inspection lasts about three to four minutes. The inspection form covers more than 20 items, including seatbelts, headlights, and tires.

Drivers like Brenda Lowrance, who also formerly worked for Yellow Cab, said such short inspections are unlikely to uncover any problems with the cars.

“They tell us to blow our horn, lights, fire extinguisher, first aid kit. Then they slap the sticker on us and let us go,” Lowrance said. “They need to make sure these vehicles are safe. We have babies that we carry. We have elderly that we carry.”

Spence agreed that the inspections seem too short.

“You can light a cigarette when you pull up, and you won’t be done when the inspection is over,” he said.

Those accusations are way off, said Andrew James, a spokesman for Executive Taxi, which also operates in Fort Worth. James said the drivers complain about Taylor only because he holds them accountable for their vehicles.

“There’s no in-between for this guy,” he said. “Gerald is respected by all of us in the industry. Gerald does an outstanding job.”

A cab company representative must be present during the city inspections, which James said are extremely thorough.

“I’ve seen Gerald fail a car because the hubcap’s missing,” he said. “Believe me, I think Yellow Cab and everyone operating in the city of Fort Worth ensures those cars are safe.”

City inspections are supposed to be at least as stringent as state inspections, according to an inspector at the Texas Department of Public Safety.

Ronald Richey, a veteran investigator of fraudulent state inspections with 23 years of experience, said it’s impossible to conduct a safety inspection in less than 15 minutes.

“When you’re talking about 20 items you’ve got to go through and check, I don’t see anyone being able to do that in a three- to four-minute time frame,” Richey said. “Unless you’re Superman, there’s just no way.”

Most people expect airbags in their cars. Federal law requires automakers to install them in vehicles. But most states, including Texas, don’t require inspectors to check for airbags. Inspectors approve vehicles even if the car’s “check airbag” light is on.

Airbags are considered safety devices that are supplemental to seatbelts. If they inflate in an accident, it’s the car owner’s choice whether to replace them.

Spence said taxi passengers don’t get that choice.

That’s why he said taxicabs should be held to a higher standard, not just for his own safety but also for the safety of the passengers. After his accident, Spence said he always questioned whether the airbags in his cab were in working order.

That’s why he said taxicabs should be held to a higher standard, not just for his own safety but also for the safety of the passengers. After his accident, Spence said he always questioned whether the airbags in his cab were in working order.

If the “check airbag” light was on in the cabs he drove after his accident, Spence said, “I was afraid to haul customers in it. When you don’t have frontal airbags, then you are putting the customers at risk. The cab contracts with the city of Fort Worth say all safety equipment must work. If the airbags aren’t in the cab, the cab isn’t safe.”

Blewey could not be reached for comment about his company’s policy on airbags.

Lowrance has worked as a taxicab driver for seven years in the Dallas-Fort Worth area. Though she has never been hurt in an accident while working, Lowrance said she has driven at least three taxicabs with a “check airbag” light glowing near the speedometer.

Some drivers are nervous about driving a cab that might not have working airbags, but if they don’t own their own vehicle, they don’t have much choice, according to Richard Devaney, who worked for Yellow Cab for eight years. Devaney spent several years completing accident investigations for Yellow Cab. He noted on his reports when the airbags had been deployed, but the company’s mechanics told him replacing airbags wasn’t part of their job.

“There were instances when airbags did not deploy,” Devaney said. “For six months, I drove one that was like that.”

The drivers said they feel anxious about more than the airbags.

Devaney said that, after accidents, other equipment — including damaged dashboards and steering columns — often were not replaced either. Those taxicabs would be reissued to drivers, he said.

“A lot of times it’s just luck of the draw in terms of what cab you get,” he said. “There are so many cab drivers and not as many cabs. If I [had] asked for another, I couldn’t have worked.”

During a periodic check-up at Yellow Cab’s repair facility in Fort Worth, Lowrance said one of the mechanics told her the taxicab needed new struts that would cost $250 each. When she asked the mechanic to replace them, he told her she wouldn’t get them.

“You just drive it until it breaks down, because they’re not going to pay for it,” Lowrance said. “Car stays with us all the time. When car breaks down, they give us another car.”

If the “check engine” light is on and the driver’s car is scheduled for a state inspection, Lowrance said Yellow Cab’s mechanics suggest the drivers reset the car’s computer by turning off the battery. The light stays off for about 75 miles, Lowrance said, which is more than enough time to pass the state inspection.

Taxicab drivers who own their vehicles are responsible for getting them inspected. The rest of the drivers lease the vehicles from the taxicab company.

Blewey said Yellow Cab exceeds what the city requires to ensure safety of its taxicabs by employing in-house mechanics to frequently check the cars for problems.

“As far as the cars that we maintain, they don’t go more than 5,000 miles without being checked,” Blewey said. “Each car has been up on our rack at least twice a month on a normal basis.”

Blewey pointed out that Yellow Cab is the only taxicab company with its own auto repair shop in Fort Worth, which improves the quality of the inspections.

“Nobody’s putting them up on a rack and checking brake pads at Taylor’s,” he said, referring to the city’s biannual inspections.

After his accident, Spence asked a Yellow Cab mechanic why the seatbelt and airbags didn’t work. He told Spence the problem for both the airbags and seatbelt was likely in the sensors, which detect when the car is in a collision. Checking those sensors requires $10,000 worth of computer equipment the Yellow Cab repair shop doesn’t have.

“The city council, instead of looking the other way, needs to do something, because next time it might be their mother or daughter in one of these cars,” Spence said.

It isn’t just the local inspections that may be problematic, but the state inspections as well. On the latter score, Spence’s concerns are shared by a major government group in the Metroplex.

In early 2008, a study by the North Central Texas Council of Government found that 86 percent of 2,200 taxicabs operating at Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport had improperly issued inspection stickers. The study looked at only one measurable item — emissions tests — but found that overall, most of the sticker inspections were so brief that there was no way they were being done properly.

“It takes a certain amount of time to look at all the features of the car that an inspector needs to inspect,” said Richard McComb, an air quality analyst with the council of governments. “The list is so big that’s it’s just impossible to do it in a short period of time.”

McComb said the study suggests a larger problem of bad inspections. “The cabs study was kind of shocking, but that’s only the tip of the iceberg,” he said. “It’s quite a problem in our whole area.”

McComb decided to check the reliability of annual taxicab inspections because it’s a large industry, and each cab is driven about 100,000 miles a year, compared to about 20,000 miles for passenger cars.

“We really didn’t go into the study with any notions of what we were looking for,” he said.

Since then, the NCTCOG has worked with DFW Airport and local police to improve the inspection process, creating a database to crack down on poor emissions enforcement.

The group focuses on air quality more than safety. McComb said it’s easier to uncover faulty inspections through emissions tests because they can be analyzed with a computer. “Inspectors can lie about everything else; they can’t lie about emissions,” he said. “There’s no data that’s being collected through an analyzer about safety like there is for emissions.”

Faulty inspections can spell disaster, and not only for the owner whose cab or other vehicle is allowed to stay on the road despite deficiencies. McComb referred to a 2008 bus crash in Sherman that killed 17 people because of unlawful tire retread and other problems.

Last November, the Texas Department of Public Safety arrested three men who worked for a business in Houston that issued inspection stickers for that bus and hundreds of other vehicles without actually looking at them. The business is called 5-Minute Inspections.

“If you’ve got an honorable inspector that’s doing his job, you’ve got nothing to worry about,” McComb said. “But if you’ve got one that’s not doing his job as a state inspector, you’ve got a problem there. You’re 100 percent at the mercy of the inspector.”

“If you’ve got an honorable inspector that’s doing his job, you’ve got nothing to worry about,” McComb said. “But if you’ve got one that’s not doing his job as a state inspector, you’ve got a problem there. You’re 100 percent at the mercy of the inspector.”

According to Spence, all of the inspections a Fort Worth taxicab undergoes each year are less than five minutes, whether done by the city or state.

Michael Morris, director of transportation for NCTCOG, said the group is aware of fraudulent state inspections of taxicabs and is working with prosecutors to address the problem.

“We find information that the taxicabs are being fraudulently inspected, and we turn that information over to the prosecutors,” he said.

If equipment is a major element of safety for cabs, driver alertness is just as important — and, according to Spence and others, just as big a problem.

It’s not uncommon for cabbies to drive 12 hours a day — the maximum allowed by city ordinance. But Lowrance said many drivers work 16 or 18 hours a day.

“They did it to make their gas money or extra money,” Lowrance said. “There’s nothing to prevent them from doing that. … The drivers can work all night long if they want.”

In response to the Weekly’s request for documents, the city produced no records showing that this portion of the taxicab ordinance is enforced.

Spence agreed that many drivers routinely work over the 12-hour limit and said that creates a potential for wrecks. “I know some drivers with other companies that will drive for 16 or 17 hours, then lay the seat back, sleep for two or three hours, and then go out and drive some more,” Spence said. “I think that’s just an accident waiting to happen.”

Many of them feel they have to work long hours in order to be able to make a decent profit after paying lease fees to the taxi companies, Spence said.

Many of them feel they have to work long hours in order to be able to make a decent profit after paying lease fees to the taxi companies, Spence said.

“Cab companies don’t enforce the 12-hours-a-day law for cabbies,” Spence said. “Drivers are forced to break the law in order to make a living.”

Blewey said it isn’t Yellow Cab’s job to prevent drivers from working too many hours. They are independent contractors, which means it is illegal for the company to exert any authority over how often they work, he said.

“The drivers have the car 24 hours a day. They work when they want to work,” Blewey said. “Some of them may work longer than that [12 hours], but they’re not required to.”

Many of the personal injury claims that come to Yellow Cab allege driver negligence as the cause, and it’s not always the passengers who end up suing.

Haslam represented a man suing Yellow Cab after one of its drivers ran over his feet in October 2005. The company refused to pay the damages, resulting in a protracted legal battle that culminated with a court order last year that Yellow Cab pay about $80,000 in damages and legal fees.

The deadline for payment has passed, and Haslam still has not received the money. “That’s kind of what the cab companies are known for,” Haslam said, “dragging it out.”

The company’s ability to “drag out” lawsuits means many people settle for much less than the medical costs of their injuries because they can’t afford the legal fees to continue, Haslam said. “The public is left out in the cold with unpaid claims,” he said.

As independent contractors, drivers are held partially responsible for lawsuits brought against the taxicab company. The agreement with Yellow Cab means any driver involved in an accident must pay at least the first $1,000 on any claim.

“Here’s who I feel sorry for: the cab drivers,” Haslam said. “They run him over the coals before the case starts.”

Blewey said his company upholds high standards of accountability, and that’s reflected in its support of increased regulation.

“We’ve always fought to keep the standards high,” Blewey said. “We want to operate in a universe with high standards.”

Blewey referred to a decision by Dallas and Fort Worth officials last year to oppose the reduction of safety standards after a group of cab companies complained that the recession and high insurance costs made it difficult to survive.

The companies suggested the age limit of taxicabs be increased to eight years and the insurance requirement be reduced. They also requested an investigation of Yellow Cab’s “monopolistic practices” because they claimed it might be violating antitrust laws.

All of the proposals were rejected.

“Lowering the insurance would have jeopardized the safety of the citizens,” said Gary Titlow, a transportation regulation manager for the city of Dallas. “They wanted to make sure there was adequate insurance to cover them.”

Titlow said Fort Worth and Dallas officials never considered an investigation of Yellow Cab on monopoly questions because they decided it was a federal issue that fell under the jurisdiction of the Fair Trade Commission.

Blewey said Yellow Cab supported the high insurance coverage and low age limit for cars. “There’s nothing out on the street older than 2006,” he said. “We were one of the big proponents of that for safety.”

He brushed off the accusations of Yellow Cab acting as a monopoly. “If you go to most of the major cities, you’ll find that there’s usually a company with most of the business,” Blewey said. “The city sets the rates and standards, not the cab companies.

Yellow Cab does control the vast majority of business in the Metroplex, but that is because it has nicer, cleaner taxicabs than anybody else, Blewey said.

“We have the most efficient dispatch in the Metroplex,” Blewey said. “You probably won’t find anybody else who has a maintenance shop in Fort Worth.”

The night of his accident, Spence left the hospital without receiving the recommended surgeries for his injured neck, back, and heart. The doctors said the heart surgery would be risky and possibly cost up to half a million dollars with long-term care — and Spence had no health insurance.

“There’s a good chance if I have the surgery I won’t survive,” Spence said. “There’s also a possibility that it [his heart] will get worse without treatment.”

Weeks after the accident, Spence asked the doctor for a note saying he was fit enough to drive taxicabs; he continued working for another seven months.

“Every day my wife and I wake up, we’re grateful because it’s another day we have together,” he said. “According to the doctors, I could still fall over dead from this heart injury tomorrow.”

The injuries continue to affect Spence’s daily routine. He has trouble breathing while asleep, causing him to wake up about once each hour. His memory and balance aren’t so good, and he is sometimes stricken with migraines or numbness in his arms and legs.

“Some days it’s not so bad,” he said. “Some days it’s horrible. It’s changed my life quite a bit.”

Eventually, Spence sued Yellow Cab, alleging that his injuries were the result of Yellow Cab’s negligence in maintaining the safety of its taxicabs.

Spence said Michael Rice, manager of Yellow Cab’s Fort Worth office, told him that he would lose his job unless he sent a letter to his attorney saying he hadn’t been injured in the accident. Spence refused and was fired.

Blewey could not be reached for comment on Spence’s lawsuit.

Spence and three other taxicab drivers have also joined forces for a class action lawsuit accusing the company of wrongfully withholding wages from hundreds of drivers.

During his last years driving cabs, Spence transported Medicaid recipients to hospitals and doctor’s appointments under a special agreement with Yellow Cab. According to the class action suit, that agreement wrongly classified the drivers as independent contractors rather than employees, forcing them to pay substantial work-related expenses, including vehicle, fuel, and cellular phone charges.

Lowrance and Devaney are part of that lawsuit, but said that their lawyers had discouraged them from discussing the case.

Until the lawsuits are over, Spence said he would not have the heart surgery. He’d like to know what’s going to happen with the court case before he takes that risk.

“I think the public is entitled to know about this,” he said. “Nobody enforces these rules. I hold the city more responsible than the cab companies. If they don’t hold the companies accountable, then they should answer to the people who get hurt.”

He added that changes need to be made to the industry he’s worked in most of his life, and it’s the passengers who will benefit the most from them.

“I volunteered to drive, and I volunteered to drive that Toyota Camry, but the people who ride in that car, they don’t volunteer to be in that car,” Spence said. “They have to ride with whoever shows up to get them.”