“Big mistake.” That was the typical response from management types at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram when I announced in February 2001 that I was jumping ship and heading to Fort Worth Weekly. The city’s only major daily newspaper had been around for 100 years and it would be around another 100, I was assured. Leaving the “mother ship,” as one editor described the newspaper, was a risky career move.

The warnings made sense. The Weekly was a five-year-old upstart then, while the Star-Telegram had outlasted every competitor over the years. Its downtown newsroom and suburban bureaus were teeming with able journalists. A computer-assisted reporting team provided support for writers. Another bunch specialized in research-intensive investigations. Seasoned beat reporters covered local governments: city hall, county government, police and fire, the school district.

The Star-Telegram proved its mettle after The Dallas Morning News opened an Arlington bureau in 1996 and began publishing the Arlington Morning News with the idea of siphoning off some Tarrant County advertising revenues. An all-out newspaper war erupted. The Star-Telegram beefed up its staff even more. Reporters at both papers poked around in every crevice of the community. The quality and scope of news coverage rose dramatically.

The Star-Telegram proved its mettle after The Dallas Morning News opened an Arlington bureau in 1996 and began publishing the Arlington Morning News with the idea of siphoning off some Tarrant County advertising revenues. An all-out newspaper war erupted. The Star-Telegram beefed up its staff even more. Reporters at both papers poked around in every crevice of the community. The quality and scope of news coverage rose dramatically.

But it was a short battle. Within a few years, the Morning News closed its bureau, and the Star-Telegram once again owned Tarrant County’s daily paper real estate.

So it’s almost inconceivable that a mere 10 years later, that same newspaper is hanging on for dear life. Multiple layoffs — the most recent in May — have cut the Star-Telegram staff almost in half. The Arlington bureau that served as ground zero during the turf war is gone now. So is the once-bustling Northeast bureau. Austin-based coverage has dwindled. Even the paper’s historic downtown building has been sold. In terms of the number of pages, the Star-Telegram is a shadow of its former self. For the first time, it actually seems possible — though still unlikely — that Cowtown could lose its last daily paper.

As is the case in other cities that have seen their daily papers go on life support, the problems in Fort Worth are partly due to the growth of the internet, which has become the place people go to first for everything from international news to help-wanted ads.

But in Fort Worth’s case, the problem also lies in who owns the mother ship. And in how big a loan they took out to buy her.

After several changes in ownership in the last few decades, the Star-Telegram is owned by the McClatchy Company, a once highly respected chain that is now struggling to stay afloat. McClatchy faces a huge debt payment in 2013, and bankruptcy could follow. Few investors are seeking to buy newspaper companies these days, especially those with decimated staffs, deteriorated products, disinterested advertisers, and dispirited readers.

“They can’t cut much more than they have already,” said industry analyst John Morton of Maryland. “They risk eroding their franchises to such an extent that it would be self-defeating.”

More than a dozen newspaper publishing companies in this country have declared bankruptcy in the past few years. Major newspapers have shut their doors, and at least one has gone to online-only format, but thus far no big American city has been left without at least one daily paper. Some papers, like the Los Angeles Times, have been so injured by the financial machinations of parent companies that their very character has been changed.

More than a dozen newspaper publishing companies in this country have declared bankruptcy in the past few years. Major newspapers have shut their doors, and at least one has gone to online-only format, but thus far no big American city has been left without at least one daily paper. Some papers, like the Los Angeles Times, have been so injured by the financial machinations of parent companies that their very character has been changed.

The fact that McClatchy is still scratching and clawing for survival bodes well for the Star-Telegram, which for many years was a cash cow for its owners. But few believe the bottom has been reached. Some staffers said they expect another round of layoffs to come this summer. And other changes loom. As the print news industry struggles with the move of revenue and readers to the internet, McClatchy and the Star-T, too, may end up putting their online content behind a paywall — a scary experiment that could help save newspapers or hasten their demise.

“I’m still one of those people who cannot believe that the Star-Telegram in particular would go away,” said 360West editor Meda Kessler, a former Star-T veteran. “People talk about this. My civilian friends say, ‘Do you think the paper will ever go away?’

“I used to say no. But I wonder, if they continue to do what they do … .”

O.K. Carter has devoted the bulk of his life to journalism, most of that time spent writing columns for the Star-Telegram. But 35 years of loyal service to an employer mean little when corporate overseers need to slash costs.

Since 2006, a reported 6,000 workers — almost half of McClatchy’s workforce around the country — have been bought out, laid off, retired, or otherwise eliminated. Several hundred of those cuts occurred at the Star-Telegram.

Carter saw the corporate guillotine glistening and retired in 2008 even though he loved his job. Nobody wrote with more authority about Arlington than the community columnist with decades of historical knowledge and a long list of sources. But those attributes, once so important to the paper and its readers, were forgotten in the face of budget cuts.

In 2010 Carter ran for the Tarrant County College board of trustees, but his old employer endorsed one of his opponents, Pat Admire. Carter beat Admire and made it to a runoff. The Star-Telegram again endorsed his opponent.

Carter won the runoff with 52 percent of the vote. In the Star-Telegram’s heyday, the paper’s endorsements could swing an election. Not anymore, he said.

“Those endorsements [for his opponents] were irrelevant because the Star-Telegram has become politically irrelevant in Tarrant County,” he said. “Thirty years ago that endorsement would have been good for a 6 to 10 percent turn. I think it’s worth less than 1 percent now.”

He believes the lack of public influence relates directly to the diminishing quality of the newspaper. “They stopped selling steak a long time ago, and frankly there’s not much sizzle left either,” he said. “It is remarkably sad.”

The Amon Carter family controlled the Star-Telegram from 1909 until it was sold for a reported $80 million to Capital Cities Communications in 1973 (two years later the Fort Worth Press closed its doors). In the last two decades, ownership has changed hands three more times. The Walt Disney Co. bought Cap Cities in 1995 for $19 billion. Two years later, it sold off four of its newly acquired newspapers, including The Kansas City Star and the Star-Telegram, to the Miami-based publishing chain Knight Ridder for $1.65 billion. Knight Ridder, the second-largest news publisher at the time, was in turn purchased in 2006 by McClatchy.

By the turn of the millennium, sites such as Craigslist had decimated newspapers’ revenue stream from classified ads. In the meantime, news “aggregators” like Google and Yahoo — or “news thieves,” as Morton calls them — were providing clients with all the news they wanted, scooped up for free from newspapers that saw the need to build an online presence but felt pressured to provide the information without requiring subscriptions or charging fees.

The Star-T staff was thrilled when McClatchy bought out Knight Ridder in 2006 for $4 billion and assumed another $2 billion in Knight Ridder debt.

McClatchy was a smaller publisher than Knight Ridder and enjoyed a sterling reputation for journalism.

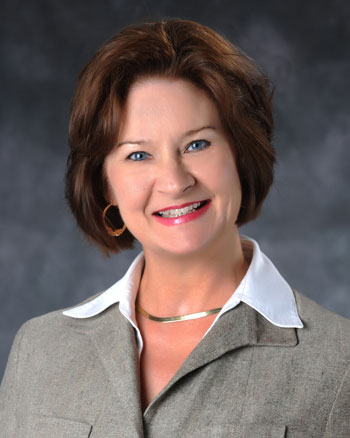

“McClatchy had so much going for it,” said former Star-Telegram editor Betsy Friauf, who resigned in 2007 as the newsroom layoffs were getting under way. “Their journalism was so well respected. They were one of the few that questioned the premise for going to war in Iraq. They questioned whether there were weapons of mass destruction when most of the major news outlets, including The New York Times, had drunk the Kool-Aid.”

But buying the United States’ second-largest newspaper company saddled McClatchy with massive debt. The traditional model for print news organizations was failing. The economy was about to nosedive. McClatchy overpaid at the worst time.

“At a time when newspapers were trending down, I thought, ‘Isn’t that a little optimistic?’ ” Friauf recalled. “We all wanted to believe in it. But it was kind of like the emperor’s new clothes.”

Not long after McClatchy took over, the Star-Telegram switched to a new layout that turned the front page into a glorified table of contents. Since then, stories have grown shorter as the paper evolved into a style reminiscent of USA Today. In the past, TV news segments would give succinct versions of local events while the daily newspaper fleshed out the story. That began to change.

Not long after McClatchy took over, the Star-Telegram switched to a new layout that turned the front page into a glorified table of contents. Since then, stories have grown shorter as the paper evolved into a style reminiscent of USA Today. In the past, TV news segments would give succinct versions of local events while the daily newspaper fleshed out the story. That began to change.

“I realize that some of you (and maybe it’s even many of you) really don’t like the new prototype and don’t understand why we should change the way we’re doing things,” Executive Editor Jim Witt wrote to employees in December 2006, shortly after McClatchy took over. “But declining circulation and readership (and the resulting loss of revenue that goes along with that) is a certain indicator that we MUST do radical things in hopes of reversing the trend.”

He ended the e-mail by saying change is “going to start happening at an even faster pace than it has been over the past 12 months. My advice is to buckle on your helmet and learn to love it.”

McClatchy CEO Gary Pruitt had characterized the purchase of Knight Ridder as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, almost tripling the number of papers the company owned, from 12 to 32. He predicted few layoffs.

Boy, was he wrong. Layoffs would soon hit most of the papers, including the Star-Telegram.

Workers fretted when Star-T publisher Wes Turner resigned in 2007. Popular with the troops, Turner had worked at the paper since 1975. McClatchy replaced him with Gary Wortel, a Canadian with no ties to Fort Worth or the newspaper — in other words, somebody with little sentiment when it came to butchering staff.

The marching orders were to “get rid of people and make them uncomfortable, and they did it,” Friauf said.

The Star-Telegram was still very profitable, but McClatchy diverted a lot of that local profit to prop up weaker papers in the chain and pay down the corporate debt.

More than four years later, the changes — and shrinkages — are still coming. The pages themselves are smaller (as are the Weekly’s) which makes it cheaper to print and easier to handle but allows less space for stories. Monday and Tuesday editions in particular have become laughably lightweight, with once-independent sections on local and business news now absorbed into the front section.

Investigative reporting has taken a backseat to bright colors and busy graphics. The loss of institutional knowledge among staff shows itself in errors that are sometimes unintentionally funny, such as when a writer encouraged readers to go listen to Django Reinhardt perform at his namesake festival, even though the guitarist has been dead since 1953. Or when the paper bragged on itself for being named the best online newspaper by the Texas Associated Press Managing Editors — and made an editing error in the first paragraph.

Reporters saw the changes as dumbing down content in favor of flash.

“There wasn’t a lot of positive feeling about it on the part of writers,” a recently laid-off reporter said. “Writers like to write. They don’t want to have to shoehorn a big story into a little box. There weren’t a lot of people applauding any of those moves.”

In June 2008, another batch of workers was laid off, and the list included some surprises, such as Gary Hardee, a popular editor and publisher in the Arlington bureau with 25 years of news experience. Over the next few years, other layoffs and buyouts were announced. People were scared and demoralized. Similar cuts were happening at all of McClatchy’s papers.

The cuts saved money, and McClatchy was making interest payments on its debt, but continuing declines in revenue meant the company could eventually default. Debt renegotiations bought time, but financial analysts began predicting bankruptcy for the publishing giant. Stock prices plummeted. In early 2009, McClatchy shares sold at 61 cents. Three years earlier, the stock had been trading at more than $70 a share. Currently, it’s at about $2.50.

The Wall Street Journal predicted bankruptcy, giving McClatchy a “1 in 2” chance of survival, citing “newspaper revenue in free fall” and stock prices down 90 percent.

In March 2009, Wortel broke more bad news in an e-mail that chilled employees. Steeply declining revenues meant “expense reductions will be more severe than originally anticipated.” Translation: Staff was cut by another 12 percent — about 100 people — and 401(k) matches were suspended. That same month, when Time magazine named the 10 newspapers most at risk of going under, the Star-Telegram made the list.

By early 2010, things were looking up a little. The company announced it had made a profit for the fourth quarter — gained by cutting staff rather than increasing revenue, but it was enough to convince lenders to give the company more time. A $264 million payment due in 2011 was pushed back to 2013. McClatchy is whittling away at its debt, perhaps enough to keep the vultures away.

“When that big payment rolls around [in 2013], the bankers may reorganize their debt structure, but who knows? There are some other companies that hoped to do that and went into bankruptcy instead,” Morton said, citing newspaper chains such as Freedom Communications, the Journal Register Company, and the Tribune Company that owns The Los Angeles Times and The Chicago Tribune.

A McClatchy bankruptcy wouldn’t necessarily be a death knell for the company or the Star-Telegram. The publisher could reorganize rather than liquidate. Earlier this year, the Star-Telegram did what was once considered unthinkable and sold its 1920s-era headquarters. After so many layoffs, the paper didn’t need the almost-200,000 square feet of West 7th Street real estate.

McClatchy’s first-quarter revenues dropped in 2011, and retailer interest in ads continued to falter. The layoffs last month were the second round this year, and Wortel released a statement blaming the recession. “Though we remain optimistic for the long term, reductions in current expenses are necessary to combat the ongoing weakness of the economy,” he said.

He wasn’t kidding — the Star-Telegram sold the desks out from under employees, doled out laptops, and told reporters to work from home. Reporters were asked to use their own cell phones for work purposes, without reimbursement.

“We’ve gotten below lean and mean — to just mean,” said a reporter who asked not to be identified.

McClatchy is part of an industry that’s swimming, if not drowning, in uncertainty these days. However, it could be that the next round of technological change will help turn things around. Paywalls and iPads could help newspapers regain some of the ground they’ve lost.

Paywalls, which require fees or subscriptions for reading content online, address the huge problem newspapers have with producing stories and pictures that feed the internet without getting paid for it. The Dallas Morning News, along with The New York Times and a few other major newspapers, instituted paywalls this year. Some had tried them in the past but caved after complaints and lost readership.

“It’s being widely tested,” said Morton “The New York Times is finding enough success there. The jury is out on whether local papers are going to find enough success.”

The Times has a national audience, and paywall subscriptions can add up. Regional papers such as the Morning News have fewer potential pockets to tap into. The News combined its print and digital subscriptions, so readers can seamlessly transfer from one “platform” to the other. But the verdict is still out on how fast readers will make the switch and what impact it will have on revenues. “In Dallas and other places, it hasn’t resulted in substantial numbers of new people signing up,” Morton said. “It’s a mixed story at this point.”

Ken Doctor wrote the book on the digital switch — literally. The author of Newsonomics: Twelve New Trends That Will Shape the News You Get said that the Times is the only major paper so far whose paywall is creating significant revenue. But he predicts the Morning News and other regional papers will eventually see their revenues increase as well. The reason? New technology, most notably the digital tablets such as iPad. About 5 million tablets have been sold, and that number is expected to reach 100 million by 2014.

Ken Doctor wrote the book on the digital switch — literally. The author of Newsonomics: Twelve New Trends That Will Shape the News You Get said that the Times is the only major paper so far whose paywall is creating significant revenue. But he predicts the Morning News and other regional papers will eventually see their revenues increase as well. The reason? New technology, most notably the digital tablets such as iPad. About 5 million tablets have been sold, and that number is expected to reach 100 million by 2014.

Doctor said smart phones and iPads are prompting many consumers to ditch print news altogether, even if it means paying for online subscriptions. More importantly, advertisers like the tablets. Surveys show readers spend more time on tablets than laptops, he said.

“The tablet will become as ubiquitous as smart phones, especially for people who read news,” he said.

McClatchy is doing a decent job of catching this new wave of tech-savvy subscribers. Last year, digital revenues made up 14 percent of its income, not far behind companies such as the Times and The Washington Post. But of course that means 86 percent of McClatchy’s revenues are still tied to print operations, which are in decline.

The news industry in general displayed an amazing ineptness when it came to embracing internet technology in its infancy. Ironically, The Star-Telegram once was on the cutting edge of that shift.

Anybody remember StarText? In the early 1980s, the paper created an online magazine that required a subscription. The site became what amounted to an early internet provider with an opportunity to transform into a Yahoo or Google. But the Star-T didn’t follow through when the internet went big-time. Instead, it followed the lead of other papers and created an online site with no subscription fee.

“In the beginning the Star-Telegram saw the future and was trying to prepare for it, but their corporate masters did not share the vision,” Carter said. “They’re paying for it now.”

Former editor Paul Harral became StarText news director in the early 1990s and pushed without success for a paywall.

“You’re giving away your product,” he said. “Had the newsgathering industry — TV, radio, newspapers — stood shoulder to shoulder and charged for the information, people probably would have gone along with it.

“The bottom line is this: No matter what you read on the internet, if it is news-related, it traces back to someone, somewhere researching information and writing a story about it,” Harral said. “That format for story delivery is virtually unchanged for the past 100 years.”

He recalled how editors in the 1990s didn’t see the computer as a serious threat because of the “three B rule,” which meant readers would stick with print unless they had technology they could take “to the bus, the bathroom, and the beach.”

What wasn’t possible back then is cutting-edge now.

“The iPad may be a whole different ballgame,” he said.

Doctor called the tablet “an unintentional gift from [Apple CEO] Steve Jobs that can be part of the revival of these companies. A big question for newspaper companies is how they are going to use the opportunity of the tablet.”

The trick for newspapers like the Star-Telegram may be keeping sufficient staff on board, producing sufficient information to retain reader loyalty until the iPad and paywall effects kick in.

“If you want to have a company that is going to come out the other end of all this, you need to preserve the two things that are going to endure — the content and the ability to sell advertising,” Doctor said. “If things get worse, and print continues to decline, and they’re not replacing those lost print revenues with digital revenues, they’ll have a hard time coming up with the money and avoiding major cuts and potential bankruptcy.”

The Star-Telegram is still Tarrant County’s paper of record, producing informative if not usually hard-hitting stories and publishing the work of some insightful columnists. Although the paper still fights for public records, it’s probably no coincidence that the Star-Telegram’s downward spiral in the 2000s has coincided with city hall’s brazenness in working behind closed doors and resisting the release of public information.

In the past several decades, a number of newspapers have bitten the dust. Most cities that once boasted several papers now have just one. In 2009, Hearst Corp.’s threat to close its money-losing San Francisco Chronicle prompted The New York Times to speculate on which large city would be the first without a daily paper.

“No one knows which will be the first big city without a large paper, but there are candidates all across the country,” the story said. However, all of those papers — including the Star-Telegram — are still publishing.

[…] reportedly laid off another dozen employees, most of them in the newsroom. This follows a downsizing trend that’s been going on for several years at the city’s only major […]