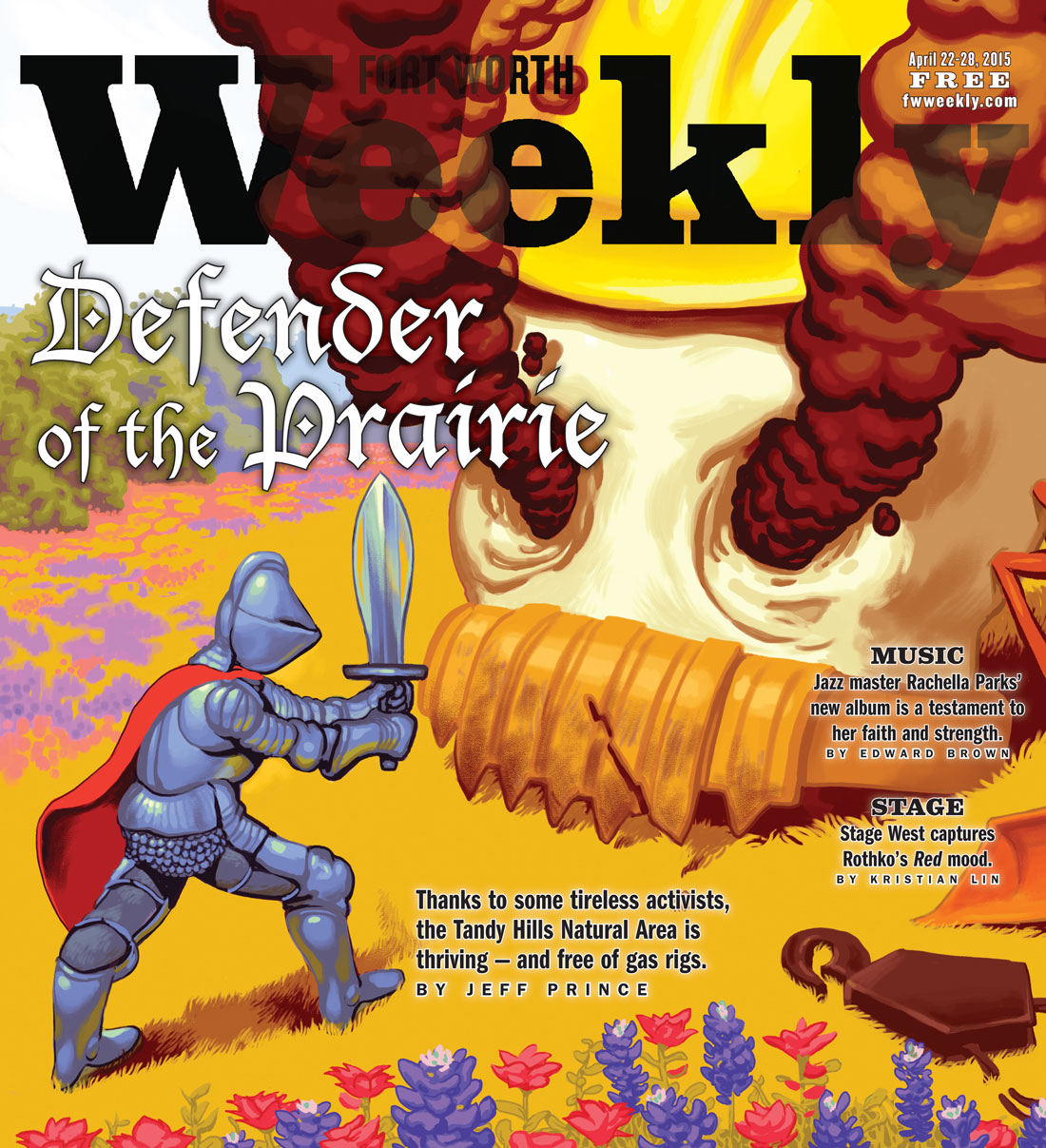

If he were a Warner Bros. character, Don Young’s jaw would have hit the floor and his eyes popped out of their sockets. But Young is a poised, quiet-spoken man by nature. His shoulders tensed up, and the adrenaline rush caused the hair on top of his head to tingle a bit, but he controlled any urge to go ballistic after a city employee mentioned in 2004 that gas drillers were eyeing the Tandy Hills Natural Area.

Young loves that 160 acres of old prairie land just east of downtown Fort Worth on the south side of I-30. The rolling hills and abundant wildlife and wildflowers are what prompted Young and his wife, Debora, to buy a house nearby in 2001. Young recalls hiking those hills as a youngster, a tradition he continues to this day.

“I was standing on the playground talking to a city parks worker in 2004, and he was talking about redoing the playground,” Young recalled. “He said, ‘Hey, I heard they’re going to drill for gas on that hill over there.’ ”

Tandy Hills was a mostly overlooked gem back then, but its hills, streams, flowers, and critters were beloved by park regulars.

“That’s when I became an instant activist,” Young said. “Before that I was not the type to protest about anything.”

Young grew up in east Fort Worth in the 1960s in an unstable family situation. Nature was a refuge, and he hid out in the woods often, including those at Tandy Hills.

“I didn’t know jack about nature and what was native,” he recalled. “I just liked the big space to get lost in and to hide in.”

As he grew older, he became fascinated with studying and photographing wildflowers, other plant life, and birds.

The Youngs attended meetings when the city was developing its gas-drilling ordinance, and they saw the deck stacked in favor of drillers. Young spoke out at meetings and even got thrown out of one for refusing to be quiet. He organized protests and picketed in front of a church that sold land adjacent to Tandy Hills to an energy company. Drillers tried to intimidate him at meetings, and city officials scorned him, but Young wouldn’t shut up.

“We were really bummed out after the task force meetings,” Debora said. “From the get-go, it looked like the deal [between the city and drillers] had already been made. It felt like a farce. Don said, ‘Let’s do something positive.’ He came up with the idea to have a festival and celebrate. We were trying to get ourselves out of the funk we were in. The wildflowers were coming on right about that time. We had a little extra money and pulled a rabbit out of the hat.”

In 2006 the first Prairie Fest drew about 200 people to the Young’s front yard. Since then, the festival has been held at the park, and attendance has grown to several thousand people. The area’s first truly green festival still shuns corporate sponsorships (as well as electricity) while putting on an event-filled day of music, learning, and communing with nature. The event has splintered into myriad side projects, keeping Young and his dozen or so volunteers hopping year-round.

Sponsorships pay for the festival, and merchandise sales and donations provide money for education and restoration programs.

In 2006 the Youngs also established the Friends of Tandy Hills Natural Area, a small group of residents working to restore and maintain Tandy Hills. Some members started another group known as Fort Worth Citizens Against Neighborhood Drilling Operations (FWCANDO) to focus on raising awareness about the dangers of urban gas drilling in the park and elsewhere in the city. The groups were kept separate because city officials were reluctant to deal with drilling protesters.

Friends of Tandy Hills created PrairieNotes, a monthly newsletter full of flower and wildlife sightings and upcoming events in the nature area. The group published its 100th issue this month; Young has written articles and posted nature photos in every one.

The Brush Bash prairie restoration event draws volunteers to help clear out invasive plants, such as privet that spread from the nearby lawns and threaten to overtake the grasslands if left unchecked. What began as an annual event is now held quarterly. City officials who clashed with Young in the beginning due to his outspokenness over urban drilling eventually began working with him, particularly after Friends of Tandy Hills Natural Area received official nonprofit status.

“I remember trying to get the city to help us set up a recycling program at Prairie Fest, but they kept saying, ‘You’re too political. We can’t do it,’ ” Young said. “The city likes to see a board of directors as a sign of commitment that you can collaborate.”

Now city crews help the volunteers clear the brush with heavy equipment and pitch in with other events as well.

The Manly Men and Wild Women Hike the Hills event is held regularly and draws people willing to hike the park from border to border.

Volunteers have established new hiking trails, closed off other trails to allow them to grow over, rescued and re-planted various vegetation, and cut brush through periodic trail construction events.

Kids on the Prairie allows schoolchildren to go on field trips and spend time studying plants and animals and their role in the environment.

“My goal is to introduce these kids to the environment and maybe produce one or two environmentalists who will grow up to be policy makers, environmentalists who will stand their ground and keep the environment safe,” Debora said.

Perhaps not since a small group of women brought attention to the Trinity River’s dirty waters in 1973 by organizing Mayfest has a tiny grassroots effort of environmentalists been so fruitful around here. Prairie Fest is now one of the city’s most unusual festivals with a major impact on the park, the community, and the city.

The city task force declared parks off- limits to drillers in 2006, although drilling is allowed underneath them from off-site locations. Tandy Hills is probably safe from industrial onslaught for many years to come, Young said.

“The mystique grew around the park, and people discovered it,” he said. “That’s what we wanted. People come here now and want to protect it. We would have the biggest protest ever if the city talked about drilling here now. People who never heard of this place five or 10 years ago would show up in droves.”

Along the way, there have been highs and lows. Festival organizers have come close to throwing in the towel a couple of times due to the number of hours involved in pulling off such an event.

But it’s here for at least one more year and maybe many more. The Youngs are delegating responsibilities while seeking new blood to lead the group into the future. They believe they’ve found new leaders. An Arlington native who moved to Fort Worth five years ago from Colorado, Jen Schultes fell in love with the park and has become co-director of Prairie Fest. Her fellow director is James Zametz, founder of Keep Fort Worth Funky, a social club designed to do just what it says, keep the city weird and wonderful.

“I needed to find someone younger to help Jen out, and James seems like an up-and-at-’em young man,” Young said. “We passed the torch on to Jen and James this year.”

******

Fantastic article, Jeff. Someday, I’d like to see a bronze statue of Don and Debora Young erected in Tandy Hills.

As noted already…fantastic article. Grassroots efforts are continuing to save the natural areas so important to life in and near any city. Thank you Don and Debra!

I looked and looked for Mayor Mike during the Fest but never spotted him. Did you see him Don?