Farrow is reminded of the epidemic every day. Her desk is loaded with folders of case files, each one bearing a photo of a beautiful child attached to a graphic description of the abuse that he or she suffered.

One file describes a 3-year-old girl who was barely able to speak after being hospitalized with skull fractures. Her infant sibling was removed and is living in a foster home. No perpetrator has been identified. The mother works two jobs and is cooperating with Child Protective Services for counseling and psychiatric evaluations.

Like many nonprofits, Farrow is short on resources. Fewer than half of the children whose case files land on her desk will be assigned a CASA. Instead, they will receive a court-appointed representative, along with CPS workers. All of whom, Farrow said, have far less time than CASAs to spend on cases.

The reality of the situation is that while child abuse and neglect are on the rise, CASA still needs volunteers. Billboard and media advertising and public speaking engagements are a few ways that the organization is trying to recruit more volunteer child advocates, Farrow said.

The process of deciding which children will get a CASA assigned to them is like “performing triage,” Lawry said.

“The factors that play into how badly a CASA advocate is needed and how quickly one can be assigned are based on risk factors and the location of the child,” she said. “We look to see how many moving pieces there are and the severity of the situation.”

Farrow and Lawry have lots of hard decisions to make. Farrow said finding volunteer child advocates is difficult for children on the outskirts of or farther from Tarrant County. A CASA also is less likely to be appointed to children currently living with relatives deemed safe or who have a history of running away.

Lawry said CASA’s work can generally be split into thirds. One third, she said, are returned to one or both biological parents. One third are placed in the foster care system and adopted, and the final third are placed in foster care but age out, meaning they have not been adopted by the time they’ve turned 18.

*****

Only one of the six kids Rowland has worked with has returned home. His six years of experience mean he is often asked to take on the toughest cases, but he’s also learned which ones to be leery of.

“My first case involved meth-addicted parents,” he said. “They had good intentions, but they couldn’t help themselves. They couldn’t make money doing anything besides selling meth. It went on and on for a year and a half.”

After 18 months, the parents had their parental rights terminated, and their child was adopted. It was bittersweet for Rowland, because the family was split, but it taught him what the job is really about — saving children.

The primary job of a CASA is to make sure the child is out of danger and not being abused in the foster home, he said. The second is to gather information on the parents, which is done mostly when they visit the child in the foster home. Not surprisingly, they tend to view the CASA as a threat, like the CPS workers who removed the child in the first place.

“Sometimes we are told [by the biological parents’ lawyer] that we cannot ask [the biological parents] questions,” Rowland said. “But the parents eventually say more at the visit than they should. You learn about their parenting style. You can learn a lot just by watching. If they talk to you afterward, they may spill the beans on whether they are smoking pot or actually have a place to stay. Maybe they are staying at a place just to get through the court proceedings. So you gather that information and put it in the report.”

Rowland’s job doesn’t stop with the parents.

“Then you find out about the relatives,” he said. “If the parents can’t take care of the child, then you have to know who else could.”

All the while, Rowland is making time to visit the victim, building a relationship with him or her by playing ball or by simply listening to whatever they want to talk about. It may sound like a lot, but he said it averages out to about 10 hours a month.

When the case finally comes to trial, CASAs like Rowland are relied on by judges as impartial advocates. The presiding judge will ask Rowland to advise the court if the child should be returned to his or her parents or not. With so much time focused on one child, volunteers like Rowland often have more insight into the dynamics surrounding a child-abuse case than CPS or any lawyers.

“CPS would like to do what’s best, but they are burdened with 50 cases each,” he said. “They have to visit each child once a month. It is an overworked and underpaid system. That’s why the system depends on somebody to gather information, to be independent and call things like they are.”

As hard as his cases have been, he said, when a child finally returns home or, more often than not, finds adoptive parents, he feels tremendously happy.

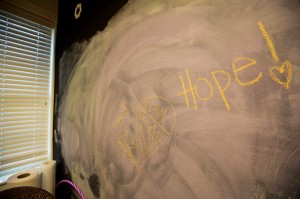

And then there are the quiet moments that need no label.

After spending two-and-a-half years in legal limbo, this young boy had finally found a home, but his foster mom knew nothing about her new child. With little fanfare, CPS had dropped the frightened boy off and left only hours earlier.

Then Rowland pulled up.

“I brought the boy a bike, and I was able to make a connection between the new mom and the boy’s whole past,” he recalled. “I stayed there all day and played with them out in the yard, to make the moment more comfortable. I also helped the new foster mom out because she had a lot of questions. They eventually ended up adopting the child. It’s the happiest case I’ve had.”

Even his worst cases end up better than they started, he said. It’s why he got involved with CASA in the first place.

“I like being around the kids,” he said. “I like seeing them going from a bad situation to a better one. They are so resilient. It’s amazing to me to this day. I’ve seen kids with half their teeth falling out who haven’t been bathed in two years. They were put in a room for two years, and within six months, they are thriving, doing well in school, playing games. It’s just amazing how quickly they bounce back.”

*****

Marissa Gonzales, spokesperson for Family and Protective Services, said CPS has no “solid theory” why Tarrant County’s rates of child abuse and neglect are so high.

“The factors that drive abuse and neglect are very complex,” she said.

Her agency recently created an Office of Child Safety to analyze child abuse rates across the state and develop theories to explain any fluctuations in the rates.

“The Office of Child Safety has reviewed and reported on at least one Tarrant County case already and is looking into several others,” she said. “We are hopeful that this new approach to trend analyses within CPS will give us some answers” in the near future.

Substance-abuse problems, CASA’s , Lawry said, are the biggest reason so many children are removed by CPS so often and may be part of Tarrant County’s puzzling stats.

“At least two-thirds of calls to CPS relate back to substance abuse in some way,” she said. “Parents might be under the influence and don’t notice their 5-year-old has left the house for hours. Mom might spend all her money on securing the substance of her addiction instead of using it toward family needs. Dad might have some dangerous acquaintances he thinks are OK to babysit for short periods [but] who end up abusing the child.”

Child abuse is not an endless cycle, said Alliance’s Rocha. Her group is actively involved in the battle to stem the tide of abuse and neglect.

“I truly believe sexual abuse is 100 percent preventable,” Rocha said. “This shouldn’t happen to any child if people are putting policy in place that eliminates situations where an adult is left alone with a child. Nearly 96 percent of cases that we worked last year was someone that child trusted. Just because someone is in a position of authority doesn’t mean they are OK to watch kids.”

Alliance is promoting an educational program called Darkness to Light. The idea is that if 5 percent of the adult population learns to prevent child abuse, a tipping point that changes behavior in the community at large can be achieved. The three-hour session teaches adults how to prevent, recognize, and react to child abuse.

Alliance and CASA staff are not only combating the effects of child abuse, Lawry said. They are combating public apathy.

“When that [Family Protective Services] report came out, we thought it was going to get traction in the media,” Lawry said.

But it did not. In fact, there’s an eerie quiet surrounding Tarrant County’s child-abuse epidemic.

“We are at a critical moment,” Lawry said. “We want reports to be made, we want these children to have the chance for a new life, but that means we need more volunteers. Right now, we have over 300 children on a waiting list for volunteers. Most people don’t realize a regular citizen can have so much impact on this problem. I have to believe that if people knew these children were on a waiting list, our phones would be ringing.”

For more information, visit www.casaforchildren.org.