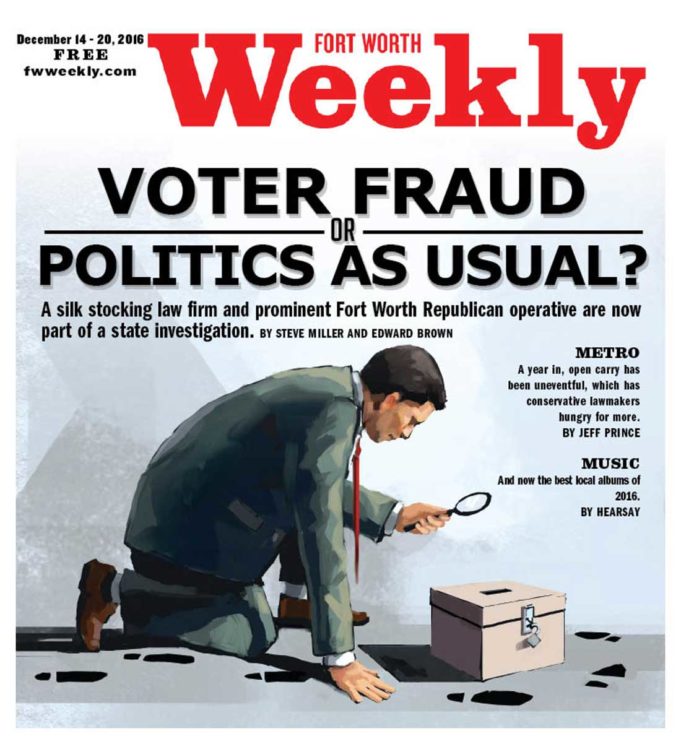

It all started with a tweet. Aaron Harris tapped out a titillating announcement in mid-October and within hours, there was a buzz.

As the executive director of Direct Action Texas, a three-year-old conservative political advocacy group, Harris had composed the most alluring social media tease he could have come up with, all from his North Richland Hills office.

Harris, a solidly built guy in his late 30s whose demeanor is a cross between an evangelical thumper and a snarky-but-lovable legal beagle, was ready to bust out the results of his group’s year-long dive into voter fraud in Tarrant County.

“Aaron Harris is about to NAME NAMES!” the tweet promised, inviting his hundreds of followers to Facebook-follow a webcast of the meeting three days later at the Elks Lodge near Monticello. On Direct Action’s website, he promised that same day that on that occasion, “for the first time publicly,” he would be “presenting what has been going on in Tarrant County relative to voter fraud.”

Except on that warm autumn evening, he failed to name names.

Instead, Harris told his crowd of 250 people that his massive voter fraud investigation in Tarrant County boils down to a top political group, an operation that is handing out money for campaigns rife with alleged fraud.

On his PowerPoint presentation, he showed an organizational chart with the names blanked out. At the top left was a blank box representing a group whose members have funded municipal elections connected to voter fraud, Harris said, insisting his evidence is “solid.”

Yet because his investigation was active, he went on, he could not “disclose the name of this group.”

Harris claimed that the group members – donating over the decades to both Republican and Democratic causes – are the “kings of graft.”

You could hear the murmured sighs of disappointment in the crowd. C’mon, man. Name names!

The headquarters of that group lies 200 miles south of Fort Worth, where the stately doors of Linebarger Goggan Blair & Sampson have been broached, if not breached, by foes before.

According to a document obtained by the Fort Worth Weekly, Linebarger is the top political group in question.

The document, assembled by Direct Action and provided to the state Attorney General’s office at the beginning of 2016, claims that Linebarger has financially backed political contests by funneling money through a cadre of pockets and accounts, the last of which allegedly belong to canvassers who, according to Harris, manipulate the mail-in ballot process.

The Austin-based law firm specializes in the indelicate task of collecting money on behalf of government agencies and is damn good at it. It has endured lawsuits in federal courts alleging unfair collection practices, heaps of internet bad-mouthing, and insider jeers from competitors for its obvious ability to gain political favor.

But until now, the firm and its hundreds of employees in offices all over the country have never been called the “kings of graft,” an unseemly title given that hundreds of cities, school districts, and counties pay millions each year to the firm, which has been in business for four decades.

“We are not aware of anything like this,” said former State Rep. Glenn Lewis, now an attorney with Linebarger, in a phone conversation with the Fort Worth Weekly. “There is just no way for us to know if a candidate is engaging in that kind of thing. We’re just a contributor, and we are not the only contributors to political campaigns. So how can just one contributor be part of voter fraud? I’m not following that at all.”

Anyone watching Harris and his engaging outline of the voter fraud investigation – the event drew 32,000 Facebook views – could wonder what the point is. Voter fraud has been a political football for decades, usually with Democrats dismissing the possibility and Republicans insisting that elections are compromised almost every cycle. State lawmakers have shown little interest in addressing the issue.

Harris claims that thousands of ballots were harvested or tampered with in the 2015 election for the Tarrant Regional Water District, in which his group backed two challengers. Mail-in ballot applications were mailed out by political operatives to be sent to specific addresses, he said. The voter would then be met at his or her residence by the operative, who would offer to help the voter cast a ballot. As Harris looked through the ballot applications and the supposed signature of the voter on the completed ballot, it appeared the latter was forged.

The tentacles of this operation, Harris now claims, stretch all the way up to the highest donor.

“It was as much a surprise to me as it was to anyone,” Harris said in a recent phone interview with the Weekly.

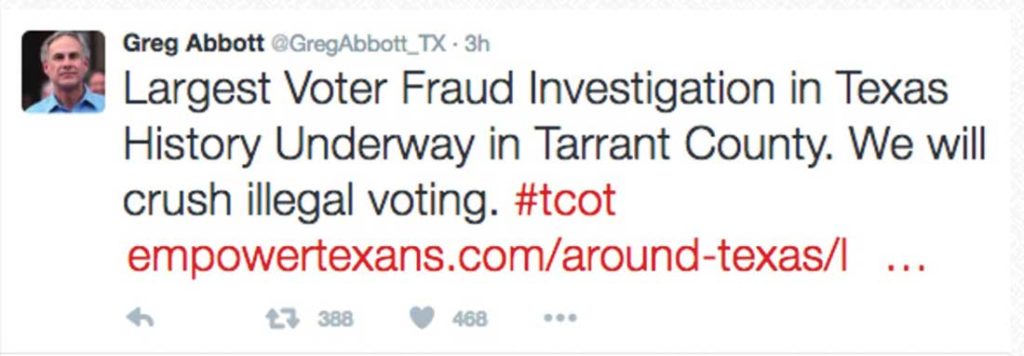

The document obtained by the Weekly is among the hundreds of pages provided by Direct Action to the state Attorney General’s office, which has resulted in what Gov. Greg Abbott calls “the largest voter fraud investigation in Texas history.” He said so in an October 6 tweet, which was retweeted by Attorney General Ken Paxton.

Harris’ group has backed conservatives and conservative issues in the past, and it was formed by Monty Bennett, the millionaire hotelier from Dallas whose political persuasion is decidedly conservative. But Harris insists the election-fraud probe was not politically driven.

“All the people who helped me were Democrats,” he said.

One of them is former State Rep. Lon Burnam, who was defeated in the March 2014 party primary by Ramon Romero by 111 votes after serving since 1997.

Burnam filed a lawsuit seeking the mail-in ballot applications to conduct his own recount. A judge denied him access, and, for a lack of money, Burnam dropped the case.

Burnam received a call from Harris after the 2015 water board race, with Harris saying he “now knew how I felt when I lost my election to voter fraud,” Burnam told the Weekly. The lifelong Democrat agreed to help Harris, providing him with the materials he had accumulated during his lawsuit.

Burnam is not crazy about being linked to a group with a reputation for conservative advocacy, but he feels he knows “the difference between the bullshit the Republicans put out and the real thing, and this thing we are talking about, this voter fraud in local elections, is real.”

*****

To anyone other than the most strident, conspiracy-worshipping gadfly, you would have walked away from the cinder block room of the Elks Lodge muttering about those crazy right-wingers and their subterfuge.

About halfway through his two-hour presentation, Harris teased the audience once more.

He noted that a highly placed Republican political operative was part of a voter fraud scheme that involves as many as 30,000 falsified mail-in ballots.

“And if I were to name him, a lot of people would be familiar with him,” Harris said.

But he didn’t.

That operative, according to the flow chart obtained by the Weekly, is Craig Murphy, a longtime Republican ally and friend to many in the state’s GOP circles. He’s a former spokesman for U.S. Congressman Joe Barton, and he was part of the team that helped Abbott end up in the governor’s mansion last year.

“We’ve never been part of vote harvesting,” Murphy told the Weekly. “Anyone can put someone’s name on a piece of paper. “

Murphy added that the inclusion of his name is likely personal: He worked on the Republican primary campaign of state representative candidate Scott Fisher in 2016, opposing the Harris-backed Jonathan Stickland.

“Aaron Harris does not like me,” Murphy said, “and [he] doesn’t miss a chance to say something negative about me.”

Or, perhaps more importantly, Murphy, Linebarger, and numerous others on Harris’ flow chart of alleged voter fraud have at one time been on the wrong side of Bennett, who has been openly waging political war for years against Tarrant County’s political establishment.

Bennett is also a supporter of several conservative-tilted political groups that work with and for him, including Harris’ Direct Action Texas. State records show that Direct Action, Texans for Local Responsibility, and Patten Research are all assumed names of Bennett’s Grassroots Groundgame, a company he formed in 2014 with Harris as the manager.

And while there are a couple of Republican names on the document obtained by the Weekly, Democrats dominate the list.

That includes former State Rep. Domingo Garcia, whose Dallas-based New American PAC has fed tens of thousands of dollars into Tarrant County campaigns. There is Stuart Clegg, the Democratic operative, as well as Pilar Candia, former candidate for Justice of the Peace in Tarrant County, and former Linebarger attorney Mario Perez.

Then there’s the powerful group of Hispanic elected officials in Tarrant County, including Fort Worth City Councilmember Sal Espino and State Rep. Romero.

All of the officials and agents deny engaging in anything illegal.

“I have seen countless campaigns reaching out to seniors and encouraging them to vote, but I have never seen anyone taking advantage of them,” said Candia, now a district director for Espino.

None of the officials, or Linebarger, is accused of direct involvement of any illegal activity, but there’s an implication that they do benefit from it.

“Who is [Harris] being paid by?” Romero asked in an interview shortly after the Direct Action event.

He didn’t wait for an answer.

“Monty Bennett. How has Monty Bennett’s success rate been in recent elections?”

Clegg, just as succinctly, wraps up the motivations for the investigation.

“I think this is about Aaron Harris and the water board election,” Clegg said.

Harris, Clegg went on, “works for Monty Bennett, and it’s a preemptive strike to keep down the Hispanic vote.”

Bennett declined an interview request but in an email said, “I financially support dozens of charities and other nonprofits, including, modestly, Direct Action Texas. It is my understanding that I’m one of many, many supporters of Direct Action Texas. Aaron Harris’ actions are his own.”

The attacks, accusations, and recriminations from both Direct Action Texas and the accused add up to a political turf war.

On one side is the Mexican Mafia, composed of Espino, Romero, and several other Hispanic elected leaders, who say they are defending their community and their jobs. No matter how the state investigation goes, Harris’ actions are already impacting Forth Worth’s political landscape.

On the other, Republicans are already benefiting from the political fallout surrounding embattled local Democratic Party officials. Last month, Espino announced that he would not run for a seventh term in the spring. In an email, he told the Weekly his reasons for bowing out are personal and “not related” to the voter fraud investigation.

*****

Harris was shocked by the returns for the water district election in May 2015. Challengers Craig Bickley and Michele Von Luckner were hammered, with neither getting even 15 percent of the vote. Harris, who served as a consultant to their campaigns, was sure they would prevail.

So on that night, Harris was distraught, as was Monty Bennett, who had contributed tens of thousands to the campaigns of Bickley and Von Luckner.

“We got smashed in that race,” Harris told the Weekly. “But our early polling data showed it was much closer than that. It just didn’t add up, the data we had before the race and the results.”

In the same election, incumbent Espino defeated challenger Steve Thornton by 26 votes.

Two contentious races, Harris thought, two dubious results.

So he asked Tarrant County if he could inspect copies of the mail-in ballot envelopes. The mail-in ballot is an option for people who are disabled, absentee, or over 65 years old.

Harris was searching for a time-honored form of fraud that has for generations been part of the election culture in South Texas, where the old school notion of patronage has carried over for generations. The majority of voter fraud cases referred to and prosecuted in the state take place in South Texas.

The practice involves the assistance provided by contractors for candidates to the mail-in voters by filling out applications for the ballots or by actually filling out the ballots. In some cases, a third party, referred to in South Texas as a politiquera, will forge the signature of a voter on the outside envelope.

State law regulating the process is straightforward: If a person is mailing in a ballot, that person must sign the ballot and envelope.

“A person other than the voter who deposits the carrier envelope in the mail or with a common or contract carrier must provide the person’s signature, printed name, and residence address on the reverse side of the envelope,” the law says.

The rule for signing a ballot for someone else – the signer is called a “witness” – is also explicit:

“The witness must state on the document or paper the name, in printed form, of the person who cannot sign. … The witness must affix the witness’s own signature to the document or paper and state the witness’s own name, in printed form, near the signature. The witness must also state the witness’s residence address unless the witness is an election officer, in which case the witness must state the witness’s official title.”

Any citizen is entitled to as many ballots as he or she wants and can request them at the Secretary of State’s website.

One evening shortly after the March primary in 2015, Harris, along with Burnam and a couple of Democratic consultants, headed over to the Tarrant County Elections Administration office, housed in what looks like an afterthought. The building, north of downtown, is faded beige and, in another life, could have been the headquarters of a trailer park.

They were there for an appointment to inspect the applications for the mail-in ballots. Within an hour of looking over the paperwork, Harris said he believed that the applications were filled out in a machine-like fashion, each address and name of the requestor scrawled in identical handwriting.

“I was in a dazed funk for three days after that,” said Harris, who then requested copies of more mail-in ballot applications and envelopes. “It was antithetical to everything I believed about the integrity of elections.”

He went to both the local and state Republican parties, seeking help to pursue his suspicion.

“I had no idea where this was going to lead me, and I was looking for an elections attorney who could explain things to me,” Harris said.

When Republicans both state and local failed to provide any help, Harris undertook the challenge on his own.

He pounded the doors of registered voters all over town, focusing on the North Side, where he saw the most discrepancies during the visit to the elections office.

He asked voters about their recent voting experiences. He enlisted specialists and ground troops, visited precincts and the elections office.

Harris claims he heard numerous tales of appropriated ballots/votes, and he believes he identified thousands of dubious ballots that would have sent Espino to defeat and possibly led to the election of the two water board challengers, Bickley and Von Luckner.

“We sent 1,500 exhibits to the Secretary of State in October 2015,” Harris said. “And they referred it to the Attorney General in January.”

Included in those documents was what he claims is evidence that Espino’s 2015 primary campaign was connected to several people close to the alleged voter fraud ring in Tarrant County, as spelled out by the flow chart provided to state investigators.

Murphy, the political consultant, and Espino’s district director Candia were paid as consultants, records show. Democratic consultant Stuart Clegg was also on board as contract labor. Linebarger twice donated to the campaign, as did Garcia’s PAC.

Espino said the fraud allegations are nonsense.

“All my workers were trained and instructed to follow the law,” said Espino, who is serving his sixth term. “We had experienced folks working with seniors.”

*****

Attorney General Paxton’s investigation in Tarrant goes much deeper than just a few instances of election fraud in municipal elections and the political persuasion of some of the alleged players.

And that’s because there is nothing small about Linebarger Goggan Blair & Sampson, whose clients include some of the biggest cities, counties, and school districts in the state and thousands more around the United States.

The firm was formed in 1998 through a merger of lawyers Oliver Heard and Dale Linebarger. They established the biggest debt collection firm in the nation, cornering the collections market in Texas and creating a one-stop shop for recouping millions of dollars for cash-strapped municipalities.

Elected officials are so reluctant to dirty their hands with such a task that they are willing to pay Linebarger up to 40 percent of a collected account, depending on the state.

The accounts Linebarger holds don’t come cheap. The firm told CNN last year that it spent more than $1 million on lobbying between 2013 and 2015. A review of campaign finance records shows that the firm or attorneys connected to it have spent millions in the last decade on political contributions for state and local candidates from both parties.

Both Gov. Abbott, who has accepted nearly $300,000 from the firm over the years, and Attorney General Paxton, who took $10,000 from Linebarger Goggan Blair & Sampson in 2014 during his election, will have to consider those donations and where it places them as the investigation moves forward.

Abbott spokesman Matt Hirsch did not return two emails and a phone call for comment. Paxton spokesman Marc Rylander did not respond to an interview request. Paxton’s office said in an email it does not comment on ongoing investigations.

Despite Linebarger’s considerable power and influence, it has also in recent years been linked to political scandal and often incendiary accusations.

In 2002, Juan M. Peña, a named partner at Linebarger at the time, resigned after being indicted in connection with the bribery of two San Antonio city councilmembers.

Peña was secretly taped as he plotted to pay $12,000 to the councilmembers in exchange for a debt collections contract. He plead guilty and was sentenced to 30 months in prison and lost his law license.

The firm was not held culpable for its partner’s actions.

In 2007, nearby Mansfield revoked the collections contract of Linebarger after Mario Perez, an attorney at the firm, made a $2,000 donation to the mayor a month after he was elected.

The next year, the firm was fired from a collections contract with the city of Chicago after it was found it covered the vacation expenses of contract officer Robert Forgue. Linebarger claimed it had picked up the tab but that Forgue would reimburse the firm.

In 2011, both the firm and partner DeMetris Sampson’s names turned up on a federal search warrant of the home of Dallas County Commissioner John Wiley Price in connection with a bribery case, several months after Sampson announced her retirement. Price has plead not guilty, and a February trial is scheduled.

In 2012, Perez, still with Linebarger, was indicted in Tarrant County on allegations that he falsified campaign reports to hide campaign contributions to an Arlington school board member.

The move came at a time when Linebarger was seeking to get the debt collections contract from the district.

Perez was fired by the firm and paid a small civil penalty. He was never prosecuted.

Linebarger was never directly implicated in the case.

Perez, now a private attorney in Forth Worth, denies wrongdoing.

Perez, who declined an interview face-to-face or by phone, said in an email, “I volunteered for [Romero’s] race for state representative in 2014 helping to design his mailers. His campaign did not have enough in the budget to do a ballot-by-mail mailer, so they certainly did not have the money to send canvassers around to help seniors vote by mail. [Romero] ran a clean race, and I think these claims are false.”

*****

Since 2002, the state Attorney General’s office has received 239 referrals for alleged voter fraud, coming from both law enforcement and the public. Four of those referrals came from Tarrant County, from 2005 and 2006. No one has been prosecuted in the county for voter fraud.

Ninety-five people have been convicted of voter- or election-related charges since 2005, including cases prosecuted by local law enforcement and the state. Of those, 51 have resulted in guilty pleas, often to lesser offenses or in exchange for a diminished sentence. Most of these offenses are misdemeanors.

Asked how common voter fraud is in Texas, Secretary of State Carlos Cascos told KERA in November, “We don’t know. I can tell you that fraud does exist. It does happen. How much of it? We’re not really sure, because not all of it may be addressed or caught. … Now, whether they can sway elections, we don’t know what those numbers are.”

His vague response to the question belies the inertia in Austin regarding policing the mail-in ballot process.

Following the 84th Legislative session in 2015, the House of Representatives filed a report that noted that among the items of importance in the future, one would be to “examine mail-ballot fraud in Texas, review recent legislative efforts to address mail-ballot fraud in Texas as well as in other states, and make appropriate legislative recommendations.”

Three bills were authored relating to voter fraud in the previous session. None addressed mail-in ballots.

The report in 2015 was similar to the report that the state House Committee on Elections filed in advance of the 80th session in 2006, which stated that “most allegations of election fraud that appear in the news or result in indictments relate to early voting by mail ballots.”

The report concluded that lawmakers in the upcoming session should “review the need to add, enhance, or reassess the effectiveness of criminal penalties provided by the Election Code. The Legislature should provide educational assistance for prosecutors and election officials to improve understanding on criminal violations of the Election Code.”

In the next session, two bills were introduced with the term “voter fraud” as part of the text. Neither mentioned mail-in ballots. Both dealt with voters’ rights.

In January 2009, before the session of the 81st Legislature, another report was issued by the House Committee on Elections. This one noted that “the committee would like the 81st Legislature to take in consideration the recommendations offered by the sub-committee on mail-in ballot integrity. As agreed by the whole committee, there is mail-in ballot fraud, and those issues do need to be addressed during the upcoming session.”

In 2011, as the Attorney General’s office stepped up its efforts to police voter fraud, more than two dozen measures were introduced during the state legislative session.

None made it out of committee.

“And it’s worse than ever now,” said Rudy Montalvo, elections administrator in Starr County, who led a coalition of South Texas elections officials to petition state lawmakers to address mail-in ballot issues.

He said the Tarrant action, like other efforts, would go nowhere.

“You cannot expect serious changes to the guidelines at the higher level,” Montalvo said, “because both the Republicans and Democrats are winning elections using these practices.”

*****

The heavy lifting for the launch of the “largest voter fraud investigation in Texas history,” in Gov. Abbott’s words, took place on the third floor of a five-story office building in North Richland Hills, Direct Action Texas’ headquarters.

It is a standard-issue dull office, the main room featuring a couple desks, a couch, and a poster espousing confrontation: An 18th-century cannon image reading, “Come and Take It.”

Most important for now are the three large maps of Tarrant County laid out on a desk, used to check district boundaries.

On a recent November afternoon, Harris, wearing a blue button-down shirt, jeans, and cowboy boots, waxed proudly on his work.

If he succeeds, it would change the way campaigning is done in Texas.

He laughed when asked if he keeps the evidence onsite, perhaps in the bulging gray file cabinet.

“Oh, no,” he said. “We’re smarter than that.”

The documents are housed offsite, he said, to minimize the risk of theft from a Watergate-style intrusion.

Harris laid a copy of an application for a mail-in ballot form from the 2015 water board elections race on his desk. As he has for state investigators, for Tarrant County officials, and for his advocates at the Elks Lodge meeting in October, Harris pointed to the signature line.

The husband’s and wife’s signatures are similar, he noted.

“Spouses might sign for each other. I’m fine with that.”

It does appear that the ballot’s final signatures didn’t match the initial application.

That, essentially, is where a practice that has endured for decades in Texas could come undone, if Harris has anything to say about it. Falsification is a crime.

Harris is embarking on a mission of mixed directions, and his intentions are either noble and righteous or vituperative and political, depending on whom you ask.

Stamping out voter fraud would be a blessing for anyone, be it citizen, political party, or elected official.

“That is the ultimate aim,” Harris said. “Lawmakers are going to be given a chance to fix it. What we have done is shown that this is here and how it is done. And I would think that in the first quarter of next year, people will be taken off in handcuffs in Tarrant County.” l

Shame shame Salvador. Very disapointing. No more taking advantage of our parents. Very ashamed in Ramon too.

This is a blatant attempt to disenfranchise elderly minority voters. Shame on anyone who attempts to deny elderly, home bound voters their right to the ballot box.