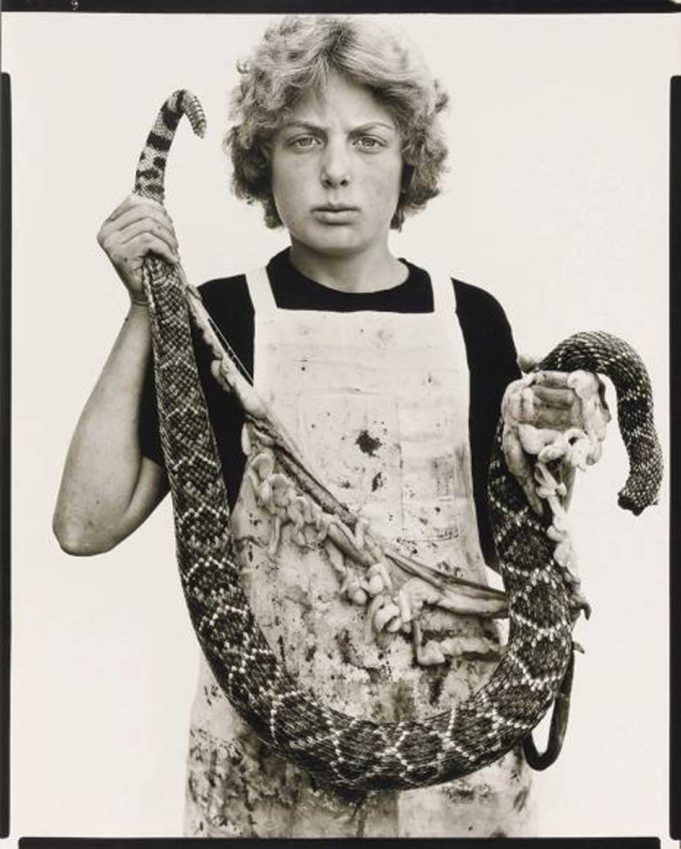

There’s nothing uniquely Texan about Avedon in Texas, especially if we exclude the two images of gentlemen in cowboy hats, including “Cotton Thompson,” a high-contrast image of a maintenance man in a silk shirt, black bowtie, and white rhinestone-accented jacket. No grand vistas of Big Bend, no cowboys herding cattle across the great West Texas plains, no other Texas clichés at all, despite the fact that in 1979 the legendary photographer was commissioned by the Amon Carter Museum of American Art to capture the people of the American West. All 17 portraits in the Carter’s current exhibit –– some of which include a truck driver, a rattlesnake skinner, and a migrant worker –– come from the original show, 1985’s In the American West.

Avedon instead photographed his subjects in black and white, isolating them in the foreground of large white backdrops with no points of reference or sense of depth and with only hints about the lives of the sitters. If not for the information on the labels revealing the date, location, and occupation of the person being photographed, these images would be timeless.

The 124 portraits in the original exhibit weren’t exactly the portraits of Texans or the American West that visitors may have hoped to see. What must have also been unexpected was the way Avedon’s photographs looked. Aside from the stark white background that seems to democratize all of his subjects, Avedon also followed the conventions of “straight photography,” using the full 8-by-10-inch negative, creating an un-cropped view, as seen through the camera lens at the moment the image was taken. The photographs, mounted onto polished stainless steel, are presented as unedited documents that are not reframed for emphasis but printed as finished compositions, revealing the artist’s intent throughout the process. The black border created when the film holder was placed against the photo paper in the printing process also serves to contain the field of white in each image, completing the composition.

If this exhibition is successful, it’s because it lies somewhere between a characteristic vivid detail and sharp focus and also because of the massive scale of the prints. There is a strong temptation to scrutinize the faces for every detail, without the intimidation that such scrutiny comes with in real life. “Jimmy Lopez, Gypsum Miner, Sweetwater, TX” from July 15, 1979, shows a close-up view of Lopez’s face caked in gypsum powder and contorted into a squint that leaves one eye opened with more than a hint of suspicion about the photographer and our own scrutinizing gaze.

In fact, this suspicion is embedded in most of the photographs, and it questions the very premise of the undertaking. It moves us beyond the ambition of the museum in commissioning a photographer, though accomplished and determined, to categorize the people of an entire region of the country as one.

In a candid conversation with John Rohrbach, senior curator of photographs at the Amon Carter, I was asked how I felt about the exhibition. “You don’t have to be polite,” he said.

I paused. But my pause wasn’t so much a search for generosity as it was a genuine curiosity about my own opinion. How do these images, taken by a rock star photographer, portray the lives of people he’d spent more than five years photographing?

“I think they present a limited and subjective view of his models, but this is coming from a person who has given up on creating more images to add to the world and instead prefers to understand the images already in it.”

Rohrbach responded that Avedon would be the first to admit that limitation, but he cautioned against reading the images too far outside the context in which they were created. Those concerns notwithstanding, it would be hard to consider these images outside of the problematic history of Orientalism, albeit with Western Americans as its focus, or the fetishizing of the Other.

There are surely more than anecdotal narratives that point to the transformational effect these photographs have had on the lives of the models and indeed on photography itself. Billy Mudd, the trucker from Alto, Texas, and subject of one of the portraits, tells of how his life was changed from a hard-drinking, knife-scarred character to a sober family man as a result of seeing himself as Avedon photographed him. There is also the argument that portraiture was transformed by Avedon’s inventive representation of subject against a neutral backdrop, among other techniques perfected over his decades-long career. But an image like “Unidentified Migrant Worker, Eagle Pass, Texas” haunts me. It skirts with the depiction of the “noble savage,” elevated to the stature of nobility through the generosity of the photographer or maybe through his indifference toward his subjects, choosing instead to attempt a summary of a group of people, which itself is a problematic proposition.

Editor’s note: This version of the story has been corrected from the original, print version.

Christopher Blay is an artist who also curates exhibitions for Tarrant County Colleges’ Art Corridor Gallery. He will be a resident artist at the Dallas Museum of Art April-June 2017.