Heads up, Tarrant County College District. You’re about to get something in the mail, and it’s not a Christmas card. Nope, it’ll be a resolution on Tarrant County Historical Commission letterhead urging you to protect the abandoned Fort Worth Power & Light Co. plant just north of downtown near North Main Street. The century-old brick, rock, and concrete plant, owned by TCC since 2004, is showing the weary signs of constant exposure to the elements. A leaky roof and broken windows are feared to be putting the building’s structural integrity at risk.

The resolution minces few words in declaring that the college has ignored the historical significance of the building and is allowing it to deteriorate.

How did we become aware of a draft resolution that hasn’t even been mailed yet? Well, the other day we ate lunch with several historical commission members, and they weren’t exactly biting their tongues. The commission was established in 1987 to save – and savor – the county’s past, and its members take pride in doing so. Their longstanding requests for the college to maintain, mothball, or sell the structure have prompted little response from administrators or the public.

“A lot of people should be interested in this, and it’s disappointing that they’re not,” said Doug Harman, a county historical commission member and former city manager.

The old smokestacks that were an integral part of the downtown landscape throughout the 20th century were torn down in 2005. The adjacent power plant remains in a prime location, just across the Trinity River from the historic downtown courthouse and near the proposed Panther Island development, we mean, “flood control project.”

In 1912, the plant became the first major source of electricity in the city. The design represents the Beaux-Arts style of architecture that was popular from the 1890s to the Great Depression. The style marries classic Greek and Roman design elements with heavy masonry and elaborate ornamentation and detailing.

In the early 2000s, the college district announced plans to create a downtown campus. District officials bought the power plant and surrounding acreage and considered incorporating the property’s structures into its campus design. In 2008, however, the college district spent almost a quarter-billion bucks to buy RadioShack’s corporate headquarters nearby and abandoned plans to build from scratch. The power plant has sat vacant and mostly untouched since the college took ownership.

In 2014, TCC board president Louise Appleman told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram that the district would work with a consultant and consider using, selling, or leasing the power plant. Historians applauded her at the time but have seen little progress.

A city-based historic preservation group, Historic Fort Worth Inc., has included the old plant on its Most Endangered Places list for much of the past decade.

In August, Harman and Jerre Tracy, the executive director of Historic Fort Worth Inc., sent a letter to Appleman urging the board to protect the power plant and pursue its inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places to receive tax credits. Susan Kline, a historic preservation consultant, completed a draft application for the registry more than 10 years ago. She said the power plant would be eligible. However, it is up to the property owner –– the college district –– to submit the registration.

“You wouldn’t think [TCC] would let [the plant] be destroyed by neglect if it was going to be on the national register,” said Bob Holmes, a county historical commission member.

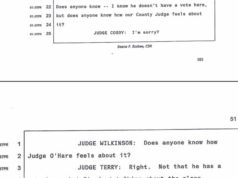

In October, Appleman replied with a brief and hardly reassuring four-paragraph letter, saying the district had no immediate plans for the property but had taken basic measures to secure the roof and windows. “Additional repairs or modifications have been researched and determined to be excessive in cost,” Appleman wrote.

Earlier this week, we walked around the plant and saw several windows partially covered up with sheet metal, although most of the windows were unprotected, with many panes broken.

Appleman ended the letter by saying, “It is our hope that completion of the Panther Island project will help us realize a suitable use of the building.”

Recent delays in funding for the $1.1 billion Panther Island project means that development could be delayed for years (“Roiling on the River,” Oct 31, 2018).

Sitting around and waiting isn’t the style of most historical preservationists. They’re trying to apply pressure to college administrators despite wielding little power since the plant has no historic designation currently. Despite Appleman’s claims, Harman said little work has been done to protect the structures.

“They’re just letting it sit,” he said.

Hey, an owner should be able to do what he wants with his own property. Right? Well, maybe. But in this case, TCC, which is exempt from paying property taxes, is sitting on a large swath of prime real estate containing culturally significant structures ripe for redevelopment.

“The college is sitting on a big hunk of land that is tax-exempt, is not being used for college purposes, and is not being marketed for sale,” Harman said. “They’re not being fair to the taxpayers of Tarrant County, when they’re sitting on a piece of land that has economic value, is tax-exempt now, and they’re not doing anything to put it on the tax rolls.”

A request for TCC spokesperson Reginald Gates to comment was not answered by press time.

Did Appleman do anything with this before she was forced to resign from the board??