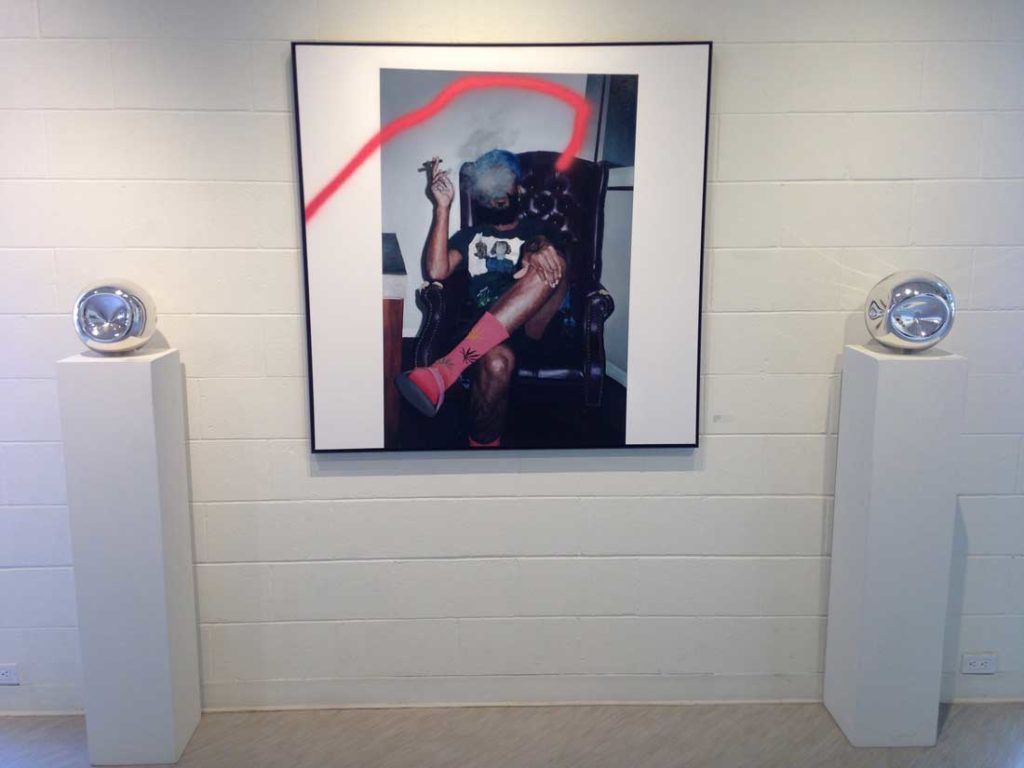

Austin Fields and Jay Wilkinson make a great team. Their dual exhibit at Fort Works Art does the seemingly impossible: brings a party right to your eyeballs. Even the ways in which the pieces are situated –– Wilkinson’s photorealist mise en scenes essentially framed by Fields’ organic-seeming, often reflective sculptures –– create the sensation of crashing someone’s way-cool pad in the middle of a throwdown. The two mirrorlike orbs on pedestals on either side of Wilkinson’s “Influence,” whose main subject is a thin and comfortably yet stylishly dressed African-American man sitting in a black lounge chair, smoking, by the hint of his marijuana-leaf socks, a spliff, look as if they’re part of the man’s comfortable yet stylish living room. The people are Wilkinson’s, the ultra-hip vibe Fields’.

Chameleon is characteristically studious but fun and intimate, with lots to take in. It’s not that there are many pieces. Each artist offers about a dozen works. It’s that the pieces on offer are so dynamic, the more time spent with them, the more they reveal. Even if it’s a distorted reflection of your face.

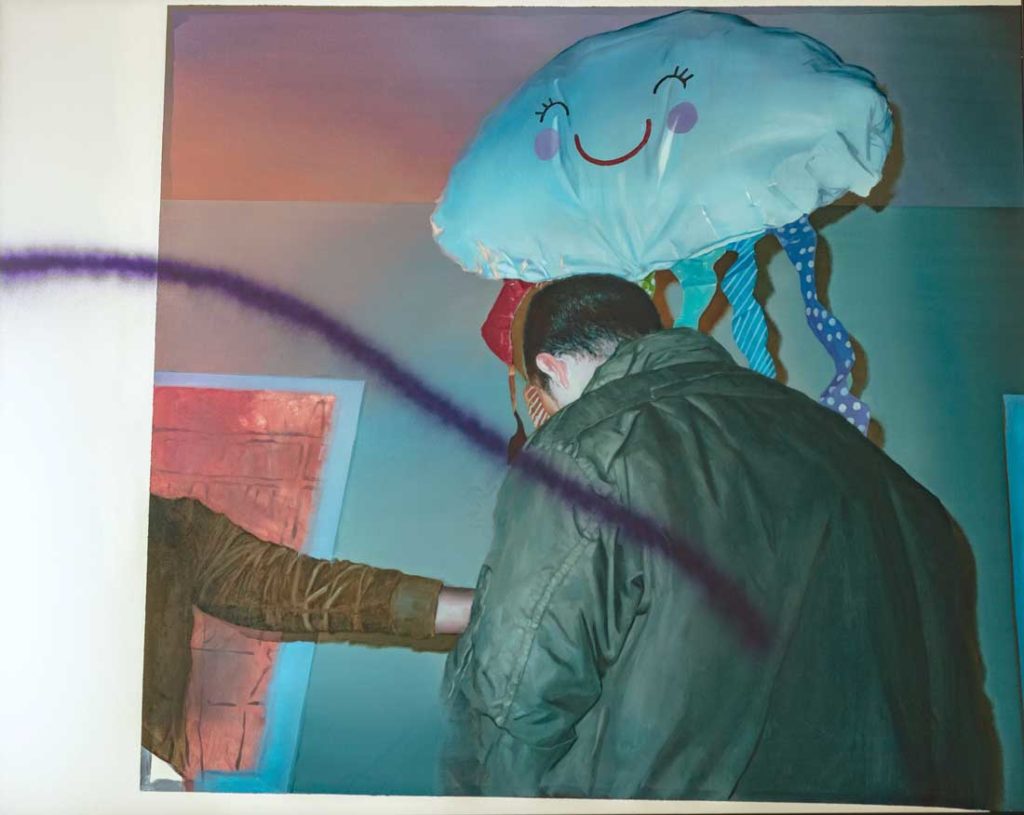

Fields, who earned her bachelor’s in fine arts in glassblowing from UTA, specializes in small-scale amorphous sculptures, all as sturdy-looking as they are ebullient. They lend a sort of elegance to the proceedings, and what gritty, lively, utterly urban proceedings they are. The self-taught Wilkinson, who recently exhibited at SCOPE/Miami Art Basel, goes for the in-between moments of life, most often of young people chilling together in a house or outdoors. Over there is a white man dropping his drawers to present his tighty whities to a campfire. Here is the back of a guy beneath a smiling Mylar balloon. Somewhere in between are a couple of in-between souls, a thin blond man with his back to us, framed by uninterested revelers in a dark room, and a long-haired, backward-ball-cap-wearing, sunglasses-indoors-sporting, all-business teenage diplomat from Itasca (probably) with his arms crossed forebodingly.

The in-betweenness extends to form of Wilkinson’s paintings themselves. The lines in a piece of fabric, the strands of hair in a head, the wreaths of smoke from the “Influence” guy’s joint –– it’s all rendered so perfectly as to seem banal. The average viewer wouldn’t waste any time on these details in a photograph. Why should she pay attention to them in a painting?

Simple: Photorealism represents the mantle of painterly achievement based solely on our primitively wrought pleasure sensors, honed as they have been over the centuries by everyone from Caravaggio to Normal Rockwell. We will always remain awed by the sweat equity on display and the precise eye. Wilkinson does photorealism one better. Not only is his in-betweenness content admirable –– based on the shapes of the content, it could even be argued that his canvases achieve a sort of abstract-expressionist grandeur –– but he introduces into nearly every scene an eerie aspect of the supernatural. There’s always a random brushstroke streaking across the surface, an ectoplasmic interjection of sorts, calling to mind a graffitist getting started right before the cops shine a spotlight on him. The result isn’t earthshattering or shocking. It is enough, however, to let the viewer know that, no, photography cannot do this, only a masterful photorealist with postmodern leanings can.

Looking at Fields’ pieces, I was initially struck by their sexless sex appeal. Maybe something about the orblike shapes with their inviting, flowing sensuality had me thinking of ladies upstairs and boys down-. The works are so distant from Wilkinson’s photo-based esthetic that they could conspire against it in any other setting. Mostly abstract where Wilkinson’s paintings are real enough to buy a beer for at the bar, Fields’ gems suggest Debussy in a world of sarcastically listened to hair-metal. Please don’t lick them.

Fields’ curvaceous lines accept the light from Fort Works Art like a mistress. Whether hanging on the walls or sitting on a shelf, most of her pieces seem to float. They are served up in the unmistakably silver sheen of a mirror or in soft pastels with a density about them that’s mostly intellectual, hardly visceral, mostly visual, hardly practical. “Crystalline” would be a good descriptor. In a world of harsh divisions and even harsher public policy, I love Fields for offering up her soft-as-a-nocturne sculptures.

And in a world of castaways, un-recycled waste, parents pimping their children on social media, and the death of democracy, I love Jay Wilkinson for making good use out of all of the images we’ve deleted from the photo albums on our phones. The in-between moments of life could arguably be the most important. They’re about the becoming rather than the being or the not being. And what could be more hopeful than that?

Chameleon

Thru Sat at Fort Works Art, 2100 Montgomery St, FW. Free, $10 donation accepted. 817-759-9475.