There have been 10 deaths tied to COVID-19 since the beginning of the pandemic at the Tarrant County Jail. Sheriff Bill Waybourn’s method of mitigating the spread of the disease within his jail was issuing half a bar of soap every other Friday to the entire population of people in jail custody. Throughout the course of his tenure as sheriff, Waybourn has repeatedly made headlines because of the abuses against people in his jail. Most recently, community members have called for his resignation over the incident involving Kelly Masten, a 38-year-old who suffers from a seizure disorder. In April, Masten was hospitalized for injuries incurred from seizures that Masten’s relatives allege resulted from inadequate medical care by Tarrant County jailers.

People are rallying around the common theme that Waybourn is failing at his job of upholding public safety in Tarrant County. Now, as the country’s infectious disease experts warn of another round of COVID-19 infections on the horizon this summer, community members are once again urging the sheriff to initiate policies of decarceration to help stop the spread of COVID-19 within his jail. The sheriff has tried six different methods of slowing the spread. All of them have failed. Therefore, the one method that he has repeatedly refused to try, which is decarceration, must be at the forefront of his priorities.

Due to the overcrowded nature of county jails, worldwide disease experts have repeatedly called for decarceral policies to create more space for social distancing within facilities. Failure to conduct decarceration inevitably leads to the rapid spread of infectious diseases within facilities and, eventually, outside of facilities due to guards, staff members, and recently released people leaving jail and entering back into their communities. Sheriff Waybourn’s refusal to initiate carceral policies and decision to carry on with “business as usual” have caused 10 reported in-custody deaths due to COVID-19 and, at its highest, 176 cases of COVID-19 among its population during the Omicron surge.

Over the past two years, I have been following the spread of the pandemic within Tarrant County Jail through the filing of dozens of open records requests. I have found that the Tarrant County Sheriff’s Department has primarily used the following six methods to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 among its incarcerated population:

- Improving inmate hygienic conditions through issuing half a bar of soap every other Friday

- Mandatory inmate mask use

- Mandatory staff mask use

- Practices related to quarantining inmates

- Practices related to detecting COVID-19 symptoms among staff through temperature checks

- The introduction of COVID-19 vaccines

Through the analysis of data concerning COVID-19 numbers among Tarrant County Jail’s incarcerated population, I have determined the above six practices to have proven ineffective because they have failed to prevent any of the four surges of COVID-19 cases among its incarcerated population since the beginning of the pandemic. In fact, during the highly infectious Omicron surge, which caused the record-high 176 cases of COVID-19 among the jail’s in-custody population, five out of six of the aforementioned practices were in place, along with the COVID-19 vaccine, yet levels of infection continued to rise. The only practice that was not in place at this time was the half-bar-of-soap practice, which was discontinued because of “limited supplies.” Much hope was centered on the introduction of the vaccine, and according to much research, it has saved countless lives. It has not stopped the spread of COVID-19 within carceral facilities. In fact, according to open records, the Tarrant County Sheriff’s Office is not even making an effort to track which detention officers are currently vaccinated.

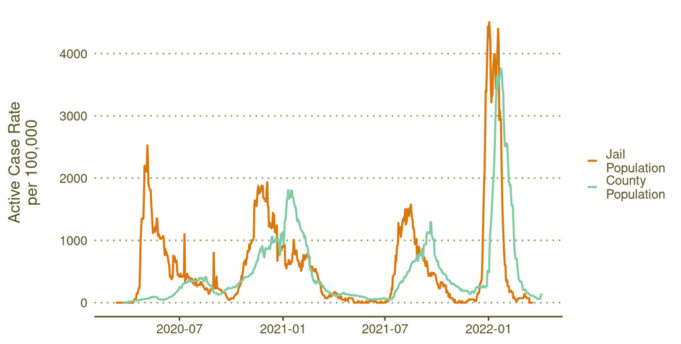

The call for decarceration is, of course, a matter of being morally just, and it is also a matter of public health. According to Neal Marquez, a researcher with the UCLA School of Law’s COVID Behind Bars Data Project, “Jail cycling has been shown to contribute to community spread in previous research. In Tarrant County, we see a pattern that is in line with such spreading where outbreaks in the jail precede outbreaks in the community. While we cannot definitively say that this process is occurring in Tarrant County, the patterns do warrant further investigation.”

We cannot say for certain that policies related to decarceration will prove effective in curbing future outbreaks within the Tarrant County Jail because it has never been tried. We have substantial evidence from other institutions throughout the nation to support our claim here. Since the six practices adopted by the Tarrant County Sheriff’s Office already failed to keep incarcerated people safe, one can only help but wonder, “Why not try decarceration?” In fact, Tarrant County Sheriff’s Office has experienced a surplus of people in its custody that has exceeded its capacity. In response, law enforcement in Tarrant County has adopted temporary practices to limit the amount of people arrested and brought into Tarrant County’s jail. On some levels, decarceral policies have already been tried in Tarrant County. Why not make them permanent? It may just prevent more senseless in-custody deaths.

Sincerely,

Jonathan Guadian, a community organizer from Fort Worth who has been following the COVID-19 pandemic within county jails in North Texas since early 2020. Guardian believes that the pandemic has only highlighted issues that have always been present in our communities regarding the fallacies of mass incarceration and the need for ending incarceration in general. Jonathan lives in Dallas.

This letter reflects the opinions of the author and not the Fort Worth Weekly. To submit a letter, please email Editor Anthony Mariani at Anthony@FWWeekly.com. Letters will be gently edited for factuality, clarity, and concision.