As a songwriter, progressive advocate, and human being living in the United States of America in the year 2024 CE, one of the main channels through which Rachel Gollay processes the moments in her life is music. Prior to the spring of 2020, her catalog contained five recordings — two full-lengths and three EPs. Her previous release, 2019’s Override, put a heavy emphasis on synthesizers and drum programming, which made for a propulsive counterpoint to her previous, folkier material while continuing to charm listeners with her gift for hooky melodies and the memorable details in her lyrics. As the realities of 2020 unfurled, Gollay turned to music to make sense of everything, and, increasingly, she was struck by the contradictions inherent to the pandemic. That’s when she became especially present to the life transitions that year fomented. All that musing, plus a major change in her own life and the war that erupted in Palestine last fall have crystalized on her new album.

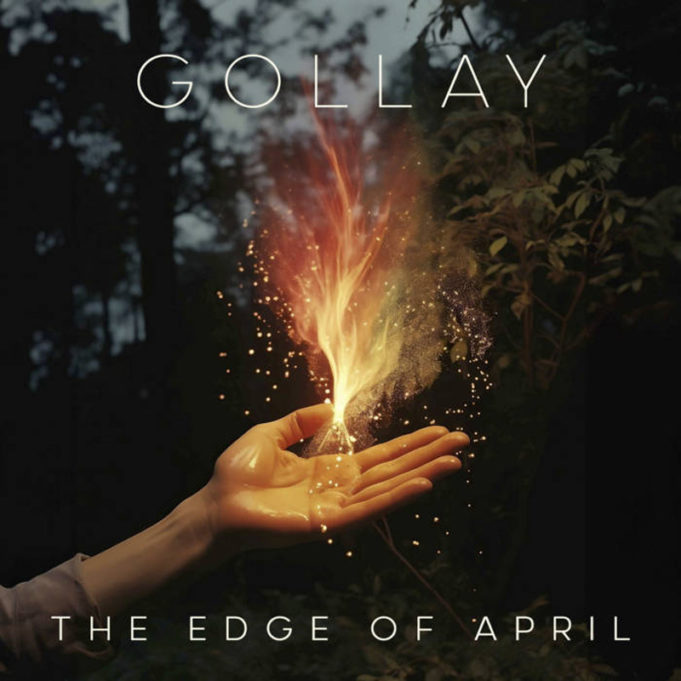

Produced by longtime collaborator Russell Jack, The Edge of April explores what she calls “life in contradiction and what it feels like to exist in moments of transition: the pressure, the inspiration, the doubt, the hope, and the ultimate peace one can find in not knowing.”

Gollay wrote the album over the course of a few years, she said, with the oldest song from 2021 or 2020. “I would say I’m always creating and writing and responding to that larger picture of the world, and I’m also processing what is happening in my personal life.”

Reflecting on that pandemic year, she said what made her feel encouraged through all the strife and uncertainty was “how people really stepped up and took care of each other, how people kind of dropped everything and were like, ‘How do we meet the basic needs of our neighbors?’ And I thought, ‘What if we were like that all the time?’ ”

Gollay is Jewish, and while she doesn’t explicitly seed her songs with the traditions of her faith, Judaism finds a way into her music. The idea of people coming together to help one another is a piece of that, as is the idea of homecoming, which became a priceless experience during the pandemic. She stresses the importance of optimism in dire times, but she’s not myopic about it. In 2020, she said, “We were in a time where we could build a completely different world. We were in a moment that felt like an opportunity, but also, ‘Are we really going to make it out of this with a newly organized society?’ And, obviously, you look around now, and we definitely put our heads back in the sand.”

This contradiction, of stressing the importance of optimism while tempering it with realism, is a main motif in The Edge of April — the opening track is called “Optimistic (Time Is Running Out).” Besides the peculiarities and tragedies of the pandemic hammering home this concept, Gollay experienced a major life transition: After a decade of working a job at a company she liked, she was let go. On the one hand, she suddenly had a lot more time to work on new music, but it also forced her to take a look at what her life at the job was really like.

“It was a great job with a great culture, until it wasn’t,” she said. “It was one of those situations where there was a lot of turmoil in 2020. The pandemic’s happening, so there’s turmoil around that, and there’s also these racial justice uprisings around George Floyd, and also, within the corporate sphere, there are all these companies going, ‘Oh, shit. Are we implicated in this in some way? How do we do business? Do we just do training? Would a meditation app fix it?’ So there was that, and, internally, there were a lot of changes in leadership in the company. The company sold to new financial interests, which, of course, can make or break things, and it really broke the culture. I was processing how much of my identity was tied up in my work and my productivity and feeling like I was influencing this company’s culture from within but also realizing that it’s just a job, that we live in capitalism. The company exists to make a profit, and it will chew up and spit out people the same way that Starbucks or any other huge company will. … I don’t know how much of that comes through in [Edge of April], but they say that the big life transitions are change in job, a death in your family, and moving to a new city.”

“And in the time that it happened, you weren’t really responding to it,” added Jack, seated alongside the singer-songwriter. “We started the album, maybe there were like three songs we started in 2021. … When we were ready to start arranging those songs, [the layoff] happened.”

“And I was like, ‘I have time on my hands,’ ” Gollay said. “ ‘I can actually work on music.’ Things that were occupying my time and energy just evaporated overnight. I think that’s when the next five or six songs came together.”

“And then you got a different job,” Jack said, “but also the songs started to reflect what was going on.”

“Some of the songs started to become like, ‘What is the message I want to tell myself right now?’ Like, ‘What’s a song I want to hear?’ And the lyrics became self-soothing in a way. ‘What’s something I need to hear that maybe other people would benefit from, too?’ ”

Jack, who is also credited with arranging, engineering, and mastering the album, said, “With Override …, I had an idea that was more modern and bombastic, and I didn’t really know how to do it, and that album was figuring that out, and doing that kind of turned into me doing most everything production-wise, and on this one, I wanted to do the opposite of that.”

“We wanted to do more and more with that one, and on [Edge of April], we wanted to do more with less,” Gollay said.

“For this album, I wanted to collaborate more. We wanted to make something with more space.”

Indeed, the 11 songs offer ample space, both sonically and metaphorically. Stylistically, you can probably file it under “folk pop,” and it is not as electronic-forward as its predecessor. But space also spreads throughout Gollay’s lyrics. In “Flyover,” she ponders what it might be like to live one’s life with one’s own wants and needs at the forefront of everything else across country “that looks the same as it did before you were born,” where “there is nothing to touch, nothing to spoil.” She references the politics of attraction (“I Want It”) and the importance of the present moment (“Moon Spell”), and both deal with distance in terms of physical bodies and between now and the future as imagined by worry.

There is also this line, regarding the future: “The world to come is an olive grove.” It’s the last line of the album, inspired by her thoughts of homecoming but also by the war in Gaza. “All of my music, I would say, is Jewish music. … The world to come is very much a Jewish concept of ‘What we are working toward?’ It’s a little bit of that ‘imagine the world you want’ idea.”

After October 7, Gollay read “a lot about Palestine pre-1948 and this image of coexistence between people, and of an attachment to the land, and of people being actually able to return to the land, in ways that are not happening in that region, or really anywhere in Western culture. We are not attached to the earth and our cycles in ways that would be nourishing to everyone, so it was kind of a pro-Palestinian song, to be totally candid, but I wasn’t trying to hit people over the head with it.”

So therein lies another contradiction, a song by a Jewish musician in support of Palestine.

“I love pluralism,” Gollay said, “and I am influenced by a lot of things, but I consider a lot of [other spiritual practices] Jewish. … Judaism [for me] is about wrestling with questions. After all, Israel means ‘to wrestle with God.’… There’s so much raw material to draw from, and I’ve had a lot of Jewish friends and teachers over the years who try to empower people to re-envision Judaism in a way that will serve the future. The olive grove, for me, is letting the people who were on that land come back to it.”