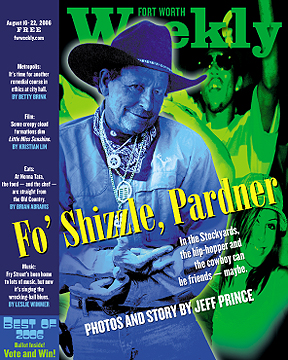

Several Stockyards country-and-western bars have closed down in recent years and reopened as dance clubs playing rap and reggaeton and getting jiggy wid the hip-hop culture — baggy clothes, graffiti, flashy neck chains, tats, sideways hats, and loads of non-cowboy bling.

Several Stockyards country-and-western bars have closed down in recent years and reopened as dance clubs playing rap and reggaeton and getting jiggy wid the hip-hop culture — baggy clothes, graffiti, flashy neck chains, tats, sideways hats, and loads of non-cowboy bling.

“It doesn’t fit what I’ve been trying to do for 30 years,” said longtime Stockyards developer Steve Murrin, a former city councilman sometimes referred to as mayor of the North Side. “It is absolutely negative to have a traffic-generating business whose nature is to be in total contrast with what the visitors who come here expect to find.”

Translation: shit-fahr!

In the gloried days of cowboy lore, plenty of disputes were settled with fists, knives, or guns. However, establishment folks and tourists who come to pay homage to those rougher times want to do so without actually dodging real bullets. For years the city has worked to tame the Stockyards into a family-friendly destination, to the applause of some business owners and to the chagrin of others. The dude with the most chips on the table is Holt Hickman, whose Exchange Avenue empire stretches east of Main Street and draws tourists to his museums, ride park, train station, Livestock Exchange building, hotel, and pay parking lots.

“My goal was to make it family-oriented, and I’ve done it,” Hickman told Fort Worth Weekly in 2002.

The area west of Main sports a wilder reputation. Sometimes the two sides don’t see eye to eye on what an entertainment district should be. Western-themed Disneyland? Sundance Square Jr.? Austin’s Sixth Street? Sodom and Gomorrah? Truth is, the Stockyards players are a splintered, bickering, competitive bunch. Still, almost everyone agreed that cruising, which gridlocked the area’s narrow streets several years ago, was bad for business. Police cracked down and ended that phenomenon (at one time a web site devoted to cruising had listed the Stockyards as one of the country’s best).

In another cleanup measure, police basically ran off the tough-looking-but-tame biker crowd that had taken to gathering near the train depot on some afternoons and evenings, by preventing them from parking their expensive bikes within sight of their barstools — a measure that generally pissed off the merchants who owned the barstools.

Police then waged a two-year battle with Club Fusion, the Stockyards’ first hip-hop club, which started strong but decayed into a thug hang-out before closing two months ago. Contrary to some expectations, the hip-hoppers and cowboys kept their distance from one another, but the hip-hoppers fought among themselves. Nowadays, the historic district is as safe as ever, helping make it one of the state’s top 10 tourist destinations by day — and a ghost town at night.

Police then waged a two-year battle with Club Fusion, the Stockyards’ first hip-hop club, which started strong but decayed into a thug hang-out before closing two months ago. Contrary to some expectations, the hip-hoppers and cowboys kept their distance from one another, but the hip-hoppers fought among themselves. Nowadays, the historic district is as safe as ever, helping make it one of the state’s top 10 tourist destinations by day — and a ghost town at night.

Ironically, thinning out the cruisers, tightening security, and running off Fusion’s rough crowd has helped to spawn a new scene. Krave, LaRumba, Club Patron, and Stone Canyon are drawing hip-hop crowds like never before. A diverse group of teen-agers, college students, and twentysomethings — Hispanics, Anglos, African-Americans, and a smattering of Asians — dance the night away without having to drive to Dallas and largely without the elements that gave hip-hop such a bad rep in many quarters: gangsters, guns, and a ghetto vibe.

Exchange Avenue club owners are giving the hip-hop customers what they want, providing a fresh spritz to an entertainment district grown musty as an old Resistol. If the current clubs continue to pull in the pesos, more are likely to spring up — another dance club has already applied for a liquor license for a spot at the far west end of the Stockyards.

Police, for the moment, are watching and wondering just how long they can keep things quiet before all hell breaks loose again. They fear that, no matter the good intentions of bar owners and the majority of hip-hop enthusiasts, where that style of music goes, trouble will follow. And they’d rather not referee any modern gunfights, especially when the tourist trade might take the bullet.

For old timers wondering what in tarnation makes a hip-hop club, just think back to the late 1970s and disco. Although today’s practitioners might be appalled by the comparison, really there’s little difference: flashing lights, sexy waitresses selling shots, and beat-laden dance tunes making everyone hot and horny and coaxing even laid-back stoners out of their shells.

Hip-hop is a catch-all term stretching well beyond the gangsta rap that garners so much negative attention and scares the bejeebers out of mainstream America. There’s a big difference between soft rappers such as Nelly, Cee-Lo, and Lyrics Born and the more hardcore styles of Lil Jon, Boyz Club, 50 Cent, Ludacris, and Jay-Z. Stockyards clubs lean toward hard rap, but often in sanitized versions. Or, as a young, white TCU hip-hopper put it, “stuff that might offend your parents but won’t offend you.”

Hip-hop is for the most part an African-American phenomenon that spread to other cultures and splintered further. Club Krave favors reggaeton, the type of urban Latin music featured on Casa 106.7-FM radio. The music incorporates rap and Caribbean influences to make a sound more distinctively cultural and danceable. While the music dates back to the late 1990s, it began catching on locally after 106.7 changed to the Hispanic Urban format last year.

Hip-hop is for the most part an African-American phenomenon that spread to other cultures and splintered further. Club Krave favors reggaeton, the type of urban Latin music featured on Casa 106.7-FM radio. The music incorporates rap and Caribbean influences to make a sound more distinctively cultural and danceable. While the music dates back to the late 1990s, it began catching on locally after 106.7 changed to the Hispanic Urban format last year.

The Stockyards, ironically, now contains easily the biggest concentration of hip-hop clubs in the city. A police officer well-versed in the scene could name only four such clubs outside the Stockyards. And even though hip-hop and gangs are intertwined in the public consciousness, police said gangbangers aren’t big on clubs since so many are underage. Gang-connected rappers prefer a migratory scene — cruising then congregating at designated hang-outs, usually a home, parking lot, lake, park, or carwash.

The Stockyards makes a sweet spot for hip-hop clubs for numerous reasons. It’s considered neutral territory and safe for various ethnicities. Rents are cheaper than in downtown. And the Stockyards allows minors (18 to 21) inside clubs as long as they don’t drink. Club owners charge high covers to make a profit and then use ink stamps or wristbands to mark underage customers. A wily kid can figure out a way to sneak a drink here or there, but, based on interviews for this story, most don’t bother. The main point is to listen to loud music, dance, have fun, maybe get lucky. Those who feel like drinking typically do so before they arrive.

Still, the old Anglo dudes — such as those who carry influence in the Stockyards — don’t particularly relish rap or any of its musical branches. Gives ’em a headache. The lyrics and attitudes come across as aggressive, rude, and threatening. The clothes are offensive.

“They have a right to be here, but we have a right to say we don’t want them here,” one shopkeeper said, his meaning clear despite the constitutional confusion.

Is it an ethnic problem? Cultural? Public safety issue? Or simply a clinging to western tradition?

Yes, yes, yes, and hell yes.

Large crowds of young people slouching around in baggy clothes and bopping to an urban beat don’t fit the carefully manicured Stockyards image, regardless of whether they behave themselves. The rock ’n’ rollers of yesterday seem tame by comparison.

“We can live with some uptempo music, but most of the people that come for the rock ’n’ roll blend in a little bit with the western,” Murrin said. “When you get the clothes that show cleavage in the rear and rows and rows of ear decorations and all that goes with that, there is no question it’s a negative to the atmosphere we’re trying to build as far as the historical preservation of the Stockyards.”

Local hip-hop artist Tahiti of PPT said people should be encouraging what’s happening in the Stockyards instead of trying to squash it. At the moment, he said, he plays the Dallas clubs regularly, in part because there isn’t much of a scene in Fort Worth.

“A lot of people go to Dallas, which is just taking money out of our city,” Tahiti said. The Stockyards “is set up for entertainment. It makes it easy for everybody to come together. That’s what it’s there for.”

But the Stockyards honchos “apparently … want to keep it like a social club and allow only certain individuals to sit there,” he said. “Nobody is saying you need to tear down the western, but you need to accommodate people living in the city, people who were born and raised here.” Grooming a local scene gives people something to do, helps to keeps them out of trouble, and keeps them close to home, he said.

But the Stockyards honchos “apparently … want to keep it like a social club and allow only certain individuals to sit there,” he said. “Nobody is saying you need to tear down the western, but you need to accommodate people living in the city, people who were born and raised here.” Grooming a local scene gives people something to do, helps to keeps them out of trouble, and keeps them close to home, he said.

Police Lt. Fred Garcia oversees the Eastside patrol district, a predominantly African-American and Hispanic part of the city. Hip-hop music and culture run deep there and aren’t pinpointed as sources of problems.

“You look in my district and most of the kids wear the baggy style of clothes, which is prevalent with inner-city youth, and a lot of the music is rap,” he said. “It’s not the music [that causes trouble], it’s up to individuals and how they conduct themselves … We have to be careful and not paint everybody with a brush and say, ‘You listen to rap or wear baggy pants so you’re a criminal.’ A person can wear the clothes of the day and listen to rap and still be on the honor roll and headed toward a college degree and the dean’s list. We don’t look at it like hip-hop means you’re a gangster.”

In the Stockyards, when cowboys brawl, it’s local color. When young blacks or Hispanics gather and fight, many of the Stockyards merchants feel, it’s an alien invasion. Then it becomes showdown at the Hip-hop Corral, and the High Sheriff’s going to win that fight.

Club Fusion is a prime example. The club raised eyebrows two years ago after opening in the shadows of Billy Bob’s Texas and catering to a young Hispanic crowd. The Stockyards is zoned for entertainment, and the powers that be don’t get to dictate to club owners what types of music must be played.

Some, however, think they tried. Billy Bob’s and the Stockyards Business Association reportedly never officially complained, but police hit hard and fast, demanding that Fusion hire more off-duty police officers to work security (referred to as “floor Nazis” by customers) and to crack down on parking-lot parties. It’s nothing new. The same police scrutiny occurred after The Cantina turned into a rock club in the 1980s and at Longhorn Saloon when young Hispanics were drawn to after-hours techno music in the 1990s.

![Murrin, standing before the Maverick Western Wear mural that depicts him as a cowboy: ‘There is no question [hip-hop] is a negative to the atmosphere we’re trying to build.’](https://www.fwweekly.com/wp-content/images/stories/images/archive/2006-08-16/feature_pic4_8-16.jpg) Murrin owned the building that housed the Longhorn during the 1990s dance craze and disliked the “rave” element in the Stockyards. But he couldn’t figure out how to evict the club owner, who was following a then-new trend of collecting a cover charge from teen-agers and letting them inside but not serving them alcohol. Murrin remembers it as “a painful time,” when his beloved Stockyards was overrun with kids on Ecstasy, dancing (and sometimes fighting) until 3 a.m.

Murrin owned the building that housed the Longhorn during the 1990s dance craze and disliked the “rave” element in the Stockyards. But he couldn’t figure out how to evict the club owner, who was following a then-new trend of collecting a cover charge from teen-agers and letting them inside but not serving them alcohol. Murrin remembers it as “a painful time,” when his beloved Stockyards was overrun with kids on Ecstasy, dancing (and sometimes fighting) until 3 a.m.

One Christmas Eve in the late 1990s, I witnessed a rave riot firsthand. The club was packed with hundreds of people, mostly young Latinos, when a fight broke out and went unabated for at least 10 minutes before police arrived in force. My date and I escaped out the door and were walking west on Exchange when we heard a commotion and saw about two dozen young men yelling and running toward us. I stopped and faced them, wondering how bad of a beating I was about to get. Luckily, they ran past me and disappeared around a corner. They weren’t running at us, they were running from police. It was an unnerving experience, and I didn’t return to Longhorn for a while.

The city saved Murrin the trouble of evicting his tenant by pursuing a nuisance abatement suit against the club operator, pointing to alcohol violations, crime, and fights as justification. The club operator relinquished the business. Even today, five years after the club went back to its country roots, people still stop in and ask about the techno dance music.

Police and Club Fusion reached an uneasy truce that held until last year, when the club changed direction and started offering live music featuring hardcore rap groups such as Too Short and Li’l Flip. Paying 20 off-duty cops $35 an hour with a four-hour minimum each can add up fast, and the owner was trying to increase his nightly take. The move backfired when thugs and gangbangers “from the south, east, north, and west” started frequenting the club, recalled Ryan Nethery, who worked behind the bar at the time.

“Once those concerts started coming in, it was all over — a bunch of gangbangers hanging out,” he said. The original crowd — Latinos, whites, and blacks — fled. “The upscale blacks won’t come to the North Side once you start getting that element in,” he said.

Nethery quit after fights became common and bar sales plummeted from an average of $2,000 a night to $500. Afterward, he ran into an off-duty Fort Worth cop who worked security there. The large African-American officer had quit Fusion as well. “The brothers got too wild; I’d rather work at the redneck bars where they’re just as crazy but at least they ain’t packing guns,” Nethery said he remembered the officer telling him.

Police went on the offensive, and the TABC suspended the club’s license for three days in March 2006. Fusion had shuttered its doors by the time the state issued an ultimatum — give up its liquor license for 30 days or pay a $30,000 fine. The vacant club remains an ominous reminder of the Stockyards’ first foray into hip-hop.

Police went on the offensive, and the TABC suspended the club’s license for three days in March 2006. Fusion had shuttered its doors by the time the state issued an ultimatum — give up its liquor license for 30 days or pay a $30,000 fine. The vacant club remains an ominous reminder of the Stockyards’ first foray into hip-hop.

Mike Costanza, who owns the Club Fusion property, has mixed feelings about police reaction. On one hand, he suspects prejudice in the way the city and TABC cracked down on a bar that attracted young minorities to a tourist area. Then again, he acknowledged that the club operator was lax in controlling the crowd.

During a meeting at the height of Fusion’s troubles, a police lieutenant “made it clear that he didn’t like hip-hop,” Costanza recalled. “They were talking about the type of clientele; of course the clientele was black.”

Police further crossed the line, Costanza felt, by threatening to take his property via a controversial nuisance abatement law that the city has used — some say abused — to crack down on apartments, clubs, and other properties that don’t meet some people’s expectations.

“Out of all the years I’ve owned real estate and been in business, I’ve never been told that before,” Costanza said. “I thought it was racist myself.”

The Stockyards establishment crowd bristles at the accusation of racism, saying they are merely protecting the district’s Western image. It’s not a race thing, it’s a cultural thing, they say. People such as former city councilman Jim Lane were adamant about integrating the Fort Worth Herd drovers with Hispanics, African-Americans, and women to fairly represent the diversity of the Old West. People of all races, creeds, and colors are welcome as long as they respect the cowboy panorama, maybe even get decked out in dude wear themselves, and preferably come carrying a wallet and camera.

Hip-hoppers show little deference to the cowboy way. Their sense of style, music, and speech derives from an urban beat. African-Americans feeling left out by white society in the 1970s created it. Rap was as much political statement as music, but the style was adapted by various ethnic groups across the country, including middle-class white kids, perhaps because it was the first musical genre they’d found that could actually piss off their parents. (It’s hard to rebel against baby-boomer parents who grew up rolling joints and listening to “White Rabbit.”)

Darren Rhea’s Neon Moon Saloon plays a mixture of urban dance music and country-and-western. He doesn’t necessarily fit the Stockyards mold and in the past has accused police of meddling, going so far as to sue the city and police for harassment. (The case was settled out of court.) Even with his past problems, he knows it could have been worse — after all, his crowd is predominantly white and includes spillover from Billy Bob’s.

Hip-hop bars “are going to continue to face the heat as long as they are playing the music that draws minorities to the Stockyards,” Rhea said. “I’m not going to say that white people don’t have their troubles too, but the powers-that-be in the Stockyards prefer that the Stockyards be white.”

To illustrate his theory, he said, Club Fusion drew steady heat (some deserved, some not) in large part because of its location and clientele. “If they were to open that club on the South Side of Fort Worth they wouldn’t have gotten near the attention they did by being in front of Billy Bob’s,” he said.

Police, though, have been heavy-handed with other clubs around town that get a reputation for violence or gang activity, such as Club Freestyle on South Riverside Drive.

Police Capt. Bill Read, who oversees the Stockyards patrol area, acknowledged that police keep close tabs on hip-hop clubs but said it’s for reasons that don’t include race or music.

“I don’t care what kind of music they play,” he said. “I’m attacking this from a public safety perspective.” Yet in the same conversation he said, “I do believe the cuss words in some of these songs incite the crowd to be more violent.”

To police, hip-hop clubs draw young, energetic crowds more prone to violence than older crowds. And since these clubs open their doors to those under 21, the chances for under-age drinking and other troubles increase. If a DJ gets everyone wired on the dance floor and then the club shoves everyone out the door all at once at closing time, it gets chaotic and leads to fights.

Interestingly, police haven’t had reports of any clashes between the cowboys and hip-hoppers. The two crowds remain separate for the most part, although some of the cowboy crowd enjoys hitting hip-hop spots late at night to get their jig on. Hip-hoppers rarely show up before midnight, long after the tourists and older crowd have gone home.

“We’ve never had the problems with an older Stockyards crowd mixing with a younger hip-hop crowd,” Read said. “Fusion was right next to Billy Bob’s, and one of my fears was the two wouldn’t mix well and there would be fighting, but there never was.”

The diversity of races inside hip-hop clubs hasn’t caused problems either.

“We haven’t had any reports of somebody being attacked because of a different ethnicity,” he said.

Fights have occurred, no doubt, because that’s what happens when youth, booze, and testosterone are mixed. The city even budgeted an additional $82,000 this year to pay for extra police officers to patrol on foot.

“The Stockyards is a safe place to go, and I consider it a good entertainment district,” Read said. “That’s my job, to make sure we keep it safe so that people can come and enjoy the Stockyards at anytime, day or night.”

One person’s public safety, however, is another’s police harassment. Stone Canyon managing partner Paul Lemon said the police attention once given to Fusion is now showering down on him, and he wonders if police are as open-minded as they claim.

A man and woman played a coy game of cat and mouse outside LaRumba.

“Not tonight,” the young woman said with a smile. “Come back tomorrow night. You have to work for it.”

That didn’t please her pursuer

“I don’t have to work for nothing; I work too hard already,” the man responded, putting his hands in his pockets and cocking his head.

They gave each other a final seductive glance and then parted. She walked toward a parking lot and disappeared into the night. He went back inside LaRumba. But there wasn’t any action there, either. The club is the newest in the Stockyards and hasn’t yet attracted a core crowd. They’ve had a big night or two, but most nights have been dismal, and even their Aug. 5 grand opening sputtered.

Just around the corner, however, Stone Canyon was pulsating. People lined up to get inside, off-duty cops working as security officers patrolled the door, and the music burst into the street.

It was about midnight on a Thursday and the Stockyards was quiet except at Stone Canyon and neighboring Club Patron, where young men and women danced, drank, teased, did the bump-and-grind, and made out under flashing lights. Exchange Avenue west of Main Street was completely lined with cars on both sides of the street, while the “family side” east of Main was barren. Hip-hop is loud and sweaty and draws a young crowd, but at least it’s drawing some action to an area that has been attracting fewer late night visitors than at any time in recent memory.

At Patron, several “club promoters” seemed more like strippers or exotic dancers, dry-humping men (and women) while staring into mirrors. The energy was intense, the crowd spirited. Stockyards dance clubs apparently have become fun enough to keep lots of Fort Worth kids from risking life, limb, and DUIs driving to Dallas to partake of that city’s hip-hop scene.

“It’s not as crowded [here] as it is in Dallas,” Araceli Rodriguez shouted over the music at Stone Canyon. “It’s a lot more dangerous there. The clubs in Dallas are way bigger than this. If it gets real crowded, the guys fight more if somebody bumps into them or something.”

The pretty 20-year-old Fort Worth resident was celebrating a friend’s birthday, and they all decided to hit the Stockyards. Had country-and-western been the only music on the menu, they and most others in the crowd likely would have headed to Dallas instead.

“We’re trying to get something to the people of Fort Worth that they have in Dallas,” said LaRumba bar manager Baron Dodson. “Fort Worth is not used to hip-hop.” He’s walking a tightrope between pleasing police and satisfying his customers.

“The town around the Stockyards has changed,” he said. “Even Billy Bob’s last weekend had Tejano bands. Right now the Stockyards is pretty dead because they are not accepting the changes that are coming ’round.”

His solution?

“We should all work together to bring people back here instead of fighting each other,” he said. “This will be the place to come in Fort Worth.”

Stone Canyon was formerly Filthy McNasty’s and Cowboy Cats before a group of investors sunk tens of thousands of dollars into renovations, including stone interior walls, fireplaces, light balls, and a kick-ass sound system. Investors soon learned that cracking into the country club isn’t easy. Western bars such as Pearl’s, White Elephant, Cadillac, and, of course, Billy Bob’s don’t leave much room for competitors. It didn’t take long for them to realize that their best hope of finding a niche was to give the young crowd what it clamored for — hip-hop. Other club owners took notice. Krave replaced the Palomino. LaRumba took over Silver Spur.

“Reality is, you can’t make it here playing Bob Wills music,” said Dave Hamman, a Stone Canyon partner. “I want to bring the North Side back. There are a lot more Latinos in the Stockyards now. The market has changed, and we’re trying to do our best to stay afloat. Country hasn’t been paying the bills.”

The change to hip-hop hasn’t been painless. Fights in bars are nothing new, but when a fight happens in a hip-hop bar, the police get antsy. Then the crackdown begins, with bar checks, citations, undercover stings, and arrests.

Lemon, of Stone Canyon, is getting an education in the art of dealing with the The Man. He’s a landscaper who decided to invest in the Stockyards club scene, not realizing the splintered factions, soap operas, and good ol’ boyism he’d have to deal with. Switching to hip-hop seemed the logical financial move, but it increased the number of minefields he’s had to negotiate.

He stops short of calling police officers racist, but said plenty of misconceptions and prejudices surround hip-hop.

“When Frankie and Bubba are fighting, it’s just good ol’ boys throwing punches,” he said. “When it’s a Hispanic with a tattoo on his arm it’s a whole different deal — it’s perceived as gang violence. It all boils down to the powers that be — TABC, Fort Worth police, people with vested interests in the Stockyards — wanting a safe environment for tourists and residents alike. They have a problem with hip-hop music down there because they feel it contributes to a delinquent attitude.”

And then something like the Cory Rodgers deal comes along and confirms the fears.

Dacor “Cory” Rodgers played wide receiver for TCU last year and was drafted by the Green Bay Packers, giving him some celebrity cachet on the night of May 26 when he and friends entered a crowded Stone Canyon. According to witnesses, some patrons began insisting that Rodgers buy drinks and give autographs, which he refused to do. A brawl involving as many as 60 people started shortly before 2 a.m. and bouncers shoved people out into the street. Police were investigating when they heard shots fired in a nearby parking lot.

Rodgers was in a car, blocked in and unable to leave, when he fired pistol rounds into the air as a warning to antagonists. Police arrested Rogers for gun possession and arrested two of his friends, both TCU football players, on suspicion of public intoxication. Rogers pleaded guilty and received probation.

The incident pulled about two dozen police officers off their beats to handle crowd control and received plenty of news media exposure because of the TCU football connection. Still, the brawl was hardly unprecedented in the Stockyards, and no major injuries were reported. So Lemon was surprised to arrive at the club the next day and find a TABC notice preventing him from selling booze for three days, even though the shooting occurred in a parking lot a block away and nobody at TABC had bothered to ask him any questions. It was the Saturday before Memorial Day, and the club had planned a big three-day weekend with C&W bands to coincide with the annual Wolfdance celebration. Cody Canada of Cross Canadian Ragweed was an expected guest, and club owners were counting on a big weekend. But they never got to plead their case.

“Do you think I have any recourse?” Lemon said. “They never had just cause to shut us down to begin with.”

The temporary closing came after a string of run-ins with police and TABC that Lemon feels were connected to his decision to play hip-hop. Others, however, say the official attention is par for the course for clubs that push the limits to make more profits. And Stone Canyon has pushed the limits. Fights have been rare with the exception of two large brawls that required police assistance, but police have cited the club for serving liquor to minors, prompting TABC to issue an ultimatum — close for 30 days or pay a $4,500 fine.

“This was on a first offense,” Lemon said. “We’re going to pay the fine because we can’t afford to be shut down 30 days.”

Police also cited the club for hosting bikini contests despite a city ordinance that restricts sexually oriented contests in the Stockyards.

The ticket that most symbolizes what Lemon sees as harassment was the one received at closing time, when the bar manager had propped the door open to let customers out. He was cited for failure to prevent varmint infestation — for giving rats a chance to sneak inside.

“Even some of the officers were laughing and saying, ‘Oh, the old failure to prevent varmint infestation,’ like they were saying, ‘Oh, he’s got your number,’ ” Lemon said.

He was summoned to a meeting with police and TABC officials and told to beef up security, enforce a dress code restricting baggy clothes, jerseys, or gang-related attire, and to shun “rolling” music, a mixture of hardcore rap and impassioned DJ banter that can incite a crowd.

“Rolling music is a term for music that pumps people up and gets them in the mood to do something stupid,” said a police officer who asked for anonymity. “You listen to the lyrics and get ready to go bust a cap in somebody’s ass. It’s like in the movie Gone in 60 Seconds, when the thieves listen to ‘Low Rider’ before they go steal cars.”

The power of music, of course, is debatable and has been blamed for suicides, murders, devil worship, and every other evil since the birth of rock ’n’ roll.

A July 16 shooting at a Dallas hip-hop club prompted Dallas police to hold a press conference, pass out lyrics to Lil Jon’s “Put Yo Hood Up,” and blame the song for igniting a gang fight that left two men dead. Dallas Morning News columnist Steve Blow wrote, “This time the link between the music and the dead is irrefutable.” The Dallas Observer, in its “Unfair Park” blog, responded under the headline, “Steve Blow Is An Idiot.”

Fort Worth police said it’s not the style of music a club plays but the number of fights, minors in possession, drunken driving arrests, and other related problems that bring heat on a club. Assaults make a city look dangerous, and high crime stats scare away potential tourists, residents, and business development. Police are under pressure to stop fights before they occur. Cracking down on bars is one way to do it.

“When there are large fights a lot of police officers have to respond,” Read said. “If I’ve got 20 officers tied up in the Stockyards I’ve got 20 officers that aren’t in the neighborhoods where they belong. I have to communicate with the clubs to make a safe environment.”

At Krave, the owner reined in early problems with fights after a come-to-Jesus powwow with police. Even so, police said a July 23 gang shootout on the South Side that injured nine people was payback for a slapping incident that had occurred between two gang members the night before at Krave. The club owner didn’t want to be interviewed for this article but characterized Krave’s crowd as laid-back and said he willingly meets with police whenever they want to talk.

Bar owners either play by police rules and control their crowd or face constant scrutiny, especially when playing urban music with a tough reputation in a cowboy entertainment district catering to families and tourists.

“They don’t want hip-hop music in the Stockyards,” Lemon said.

That’s fo’ shizzle.

You can reach Jeff Prince at jeff.prince@fwweekly.com.