The sparse but enthusiastic faithful are here to see the Fort Worth Flyers win their fifth game out of the last six. The Flyers fall behind early to the visiting Bakersfield Jam, and 6’9” starting power forward Pops Mensah-Bonsu is sent to the bench with foul trouble. Still, the home team never seems in danger of losing control of the game, and they obliterate Bakersfield in the third quarter behind the play of point guard Juan José “J.J.” Barea for an easy 124-116 victory. The crowd, boosted by a number of kids who are all too happy to scream for the home team, goes home content.

The sparse but enthusiastic faithful are here to see the Fort Worth Flyers win their fifth game out of the last six. The Flyers fall behind early to the visiting Bakersfield Jam, and 6’9” starting power forward Pops Mensah-Bonsu is sent to the bench with foul trouble. Still, the home team never seems in danger of losing control of the game, and they obliterate Bakersfield in the third quarter behind the play of point guard Juan José “J.J.” Barea for an easy 124-116 victory. The crowd, boosted by a number of kids who are all too happy to scream for the home team, goes home content.

A street-corner survey anywhere in Fort Worth (except outside the convention center on game nights) would probably turn up few locals who even know who the Fort Worth Flyers are, despite the fact that the team is in its second year here. News stories have been sparse, and the minor-league hockey team the Brahmas, displaced by the Flyers at the convention center, at least got novelty coverage every now and then. Yet the Flyers are a big-time operation. They play in the National Basketball Association’s Developmental League, known as the D-League, just one level below the NBA. They are affiliated with the Dallas Mavericks, as well as the Philadelphia 76ers and Charlotte Bobcats, which means that local fans can sometimes see players in the minors one day and then watch them hit the big leagues the next week. Indeed, that’s exactly what happens for Barea and Mensah-Bonsu, who are called up to the Mavericks soon after this game.

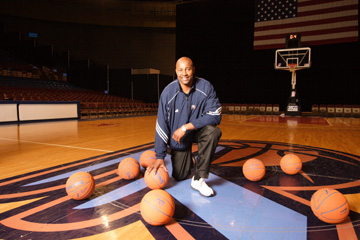

In charge of preparing these athletes for the NBA (and, not incidentally, winning games for the Flyers) is a man who knows exactly what it takes to succeed as an NBA player. Shaven-headed and impeccably groomed, Sidney Moncrief calmly strides the sidelines with his arms crossed while his players methodically dispatch their opponents. With the former NBA All-Star and defensive standout in charge and the Mavericks next door taking the pick of the Flyers litter, the D-League doesn’t seem like a basketball backwater, even if the crowd could comfortably fit in Little League bleachers on some nights. In fact, fans who get a thrill out of being in on the early days of NBA stars ought to keep their eyes on the Flyers sidelines as well as the court. Some of the game’s greatest coaches have come from the minors, and some observers think Moncrief could be the next one.

Drafted out of the University of Arkansas in 1979 by the Milwaukee Bucks, Moncrief played 10 of his 11 NBA seasons in Wisconsin under Don Nelson, then head coach of the Bucks. Moncrief never had a losing season as a player. While he was an efficient scorer (four seasons averaging over 20 points a game, four All-Star appearances, and a career shooting percentage of better than 50 percent), the 6’4” guard was known for his lockdown defense. He won the NBA Defensive Player of the Year honors in 1983 and ’84, the first two years that that award was given out. Moncrief’s skills and competitive spirit drew the admiration of no less than Michael Jordan. “When you play against Moncrief, you’re in for a night of all-around basketball,” the Chicago Bulls star told the Los Angeles Times. “He’ll hound you at both ends of the court. You just expect it.” When Moncrief’s deteriorating knees ended his playing career in 1991, he went home to Arkansas and embarked on a number of business ventures, including a Buick dealership that he sold in 1999. His people skills had Arkansans envisioning a future in politics, and the state’s then-governor Bill Clinton once joked, “The only comfort I can take from having the smallest governor’s salary in the nation is that it might stop Sidney Moncrief from running against me.”

Rather than go into politics, Moncrief wanted back in basketball. He served as head coach of the University of Arkansas at Little Rock for the 1999-2000 season. After that, he sought out the coach who’d done so well by him with the Bucks and joined the Mavericks as one of Don Nelson’s assistant coaches, where he stayed for three years. Current Mavs general manager Donnie Nelson, who worked alongside him in those days, said Moncrief’s playing and coaching experience has prepared him well for his current job. The Flyers’ record, he said, “definitely reflects what he brings to the table.” During his time with the Mavs, Moncrief also returned to the car business. He bought a Hyundai dealership in Pine Bluff, Ark., in 2001. The sale of the franchise three years later ended up in court, with Moncrief and the new owners suing each other. (The new owners have since been sued themselves by Hyundai.) His other dealership in Edmond, Okla., closed less than a year after it opened in 2003, amid lawsuits alleging nonpayment of advertising bills and employee wages.

Rather than go into politics, Moncrief wanted back in basketball. He served as head coach of the University of Arkansas at Little Rock for the 1999-2000 season. After that, he sought out the coach who’d done so well by him with the Bucks and joined the Mavericks as one of Don Nelson’s assistant coaches, where he stayed for three years. Current Mavs general manager Donnie Nelson, who worked alongside him in those days, said Moncrief’s playing and coaching experience has prepared him well for his current job. The Flyers’ record, he said, “definitely reflects what he brings to the table.” During his time with the Mavs, Moncrief also returned to the car business. He bought a Hyundai dealership in Pine Bluff, Ark., in 2001. The sale of the franchise three years later ended up in court, with Moncrief and the new owners suing each other. (The new owners have since been sued themselves by Hyundai.) His other dealership in Edmond, Okla., closed less than a year after it opened in 2003, amid lawsuits alleging nonpayment of advertising bills and employee wages.

It was during this time that Moncrief left the Mavericks. About that decision, he would only say, “There was some uncertainty at the time regarding Coach Nelson’s situation. I wanted to do something different.” The lawsuits were all settled in 2005, the year Moncrief filed for bankruptcy — a matter he has repeatedly refused to discuss with reporters. Given all that, the coaching opportunity with the Flyers, next door to the Mavericks, may have seemed a golden opportunity for Moncrief. He isn’t daunted by starting his coaching career from a lower rung. “It’s refreshing to be back in basketball,” he said. “Coaching isn’t difficult for me, and being in Fort Worth has been a great learning experience.” He continues to live in Dallas with his wife and sons, two of whom play football.

He brought to the year-old team a high-scoring, high-energy style of basketball reminiscent of Nelson’s Mavericks and the other NBA teams that have played “Nellieball.” “Our style of play is up-tempo but under control,” said club president Ken Nicholson, who joined the team this season along with Moncrief. “It isn’t street ball. If the fast break isn’t there, we’ll set up our offense in the half-court.” Moncrief agrees with that description. He cites Nelson’s influence in his own willingness to use unorthodox lineups to create matchup problems for the opposition. However, he also adds his own signature — an emphasis on defense, something Nelson’s teams were never known for. As a coach, he tries to pass on to his players the same sort of defensive intensity that was his trademark as a player — a hard sell, sometimes, with players who know that filling up the stat sheet with offensive numbers is the easiest way to catch scouts’ attention. “We have to make defense second nature to them,” the coach said. “We need players who can support each other. I try to help them by giving them a system that’s easy to memorize without too many rules.”

This is the order of the day at Nolan Catholic High School, where the Flyers practice. They go through three-on-threes, five-on-fives, transition, and half-court sets, with a particular emphasis on defensive positioning and pressuring opposing guards in the back court. The nasal baritone voice of assistant coach Paul Mokeski (a former Dallas Maverick, as well as a longtime teammate of Moncrief’s in Milwaukee) booms out “No middle! No middle!” through the mostly empty gym, as he exhorts the Flyers’ defenders to keep the men they’re guarding out of the lane. While Mokeski does most of the hard driving, Moncrief prefers the calm, authoritative approach to instructing his players, though his frustration occasionally surfaces. There’s no Bobby Knight-style berating of his own players or officials during games. (“I’m pretty intense,” he said. “You just don’t hear it. But when I have something to say to my team, they hear me.”) The atmosphere at practice is focused but never unpleasantly tense.

This holds true even after an incident midway through the session, when the Flyers’ sharpshooting 6’6” swingman Terrance Thomas dribbles into a blind alley rather than passing the ball as the system dictates. A few seconds later, after giving up the ball, Thomas works to an open spot behind the three-point line, receives the pass, and nails the shot. Moncrief, however, is still displeased about the earlier mistake and lets Thomas know it. Perhaps feeling unappreciated, Thomas audibly says to himself, “Nice shot, Terrance.” Moncrief explodes in disbelief, “ ‘Nice shot, Terrance’? Who the fuck are you trying to show up?” and promptly tosses the player out of the gym. Interviewed a few weeks later, Thomas was clearly embarrassed by his outburst. While he wouldn’t discuss the incident itself, he said, “I’m so grateful to be playing for such a great coach. He and Coach Mokeski know so much about the game, and they pass that on to us, and that helps us become better players.”

This holds true even after an incident midway through the session, when the Flyers’ sharpshooting 6’6” swingman Terrance Thomas dribbles into a blind alley rather than passing the ball as the system dictates. A few seconds later, after giving up the ball, Thomas works to an open spot behind the three-point line, receives the pass, and nails the shot. Moncrief, however, is still displeased about the earlier mistake and lets Thomas know it. Perhaps feeling unappreciated, Thomas audibly says to himself, “Nice shot, Terrance.” Moncrief explodes in disbelief, “ ‘Nice shot, Terrance’? Who the fuck are you trying to show up?” and promptly tosses the player out of the gym. Interviewed a few weeks later, Thomas was clearly embarrassed by his outburst. While he wouldn’t discuss the incident itself, he said, “I’m so grateful to be playing for such a great coach. He and Coach Mokeski know so much about the game, and they pass that on to us, and that helps us become better players.”

“It was definitely out of character for him,” Moncrief said of the incident, stressing that he and Thomas are now cool. “The worst thing a coach can do is hold a grudge. We have to show that we care about our players as people and set boundaries. I’ve known coaches who hold grudges against players forever, for things they say out of anger. That isn’t good. Forgiveness is a powerful tool.” While his players are learning the skills that could take them on to the NBA, Moncrief is learning as well. His most important lesson thus far? “Game management,” he responded immediately. “I’ve always been good at teaching and managing people. It’s making personnel adjustments and managing the clock that I have to learn.” He sees the job as a steppingstone to being a head coach in the NBA or at an NCAA Division I school.

Because the Flyers were in first place in the D-League’s Eastern Division at the season’s halfway point, Moncrief was tapped to coach the East team (which features two of his own players) at the inaugural D-League All-Star Game, held as part of the festivities during the NBA’s All-Star weekend in Las Vegas. That weekend in mid-February has since become notorious for the strip-club arrest of NFL defensive back Pacman Jones, which many sportswriters used as an example of the weekend’s atmosphere of lawlessness and mayhem. Moncrief, however, said all that passed him by unnoticed at the time. “I didn’t go out,” he said. “I just stayed in with our guys, gave them a bit of a system, and let them go out and play. It was fun doing that.” Under Moncrief’s guidance, East scored a 114-100 win, with Mensah-Bonsu scoring 30 points and garnering an MVP trophy for the game. It’s an impressive performance for representatives of one of the D-League’s newest teams. The D-League itself isn’t much older than the Flyers. It was started in 2001 with eight teams owned by the NBA, concentrated in the South. After four years, the teams were sold to private owners and relocated in places from California to Florida. At about the same time, four teams remaining from an earlier, now-defunct minor league — the old Continental Basketball Association, whose roots went back to 1946 — joined the D-League.

When the NBA held its team sale, the firm of Southwest Basketball LLC, led by former Indiana Pacers general manager David Kahn, bought three of those franchises, plus the rights to the expansion team that became the Flyers. (Southwest also owns the teams in Austin, Tulsa, and Albuquerque.) Among the investors in Southwest are Fort Worth real estate entrepreneurs Gary Walker (SCM Industries), and Tim Berry and Jason Keen (N3 Capital). With one original team since deactivated, the league is holding steady at 12 clubs. In their first year, under head coach Sam Vincent, the Flyers compiled the best regular-season record in the D-League, and they currently bill themselves as last year’s “regular-season champions,” which is slightly misleading. They fell short in the playoffs, losing at home to the Albuquerque Thunderbirds in the championship game. Even so, the Flyers were an immediate success story, by league standards. Vincent was hired as an assistant for the Dallas Mavericks, and leading scorer Ime Udoka went on to play for the Nigerian national team at the World Basketball Classic. After that he was signed by the Portland Trail Blazers and has become a starter on a rebuilding team.

When the NBA held its team sale, the firm of Southwest Basketball LLC, led by former Indiana Pacers general manager David Kahn, bought three of those franchises, plus the rights to the expansion team that became the Flyers. (Southwest also owns the teams in Austin, Tulsa, and Albuquerque.) Among the investors in Southwest are Fort Worth real estate entrepreneurs Gary Walker (SCM Industries), and Tim Berry and Jason Keen (N3 Capital). With one original team since deactivated, the league is holding steady at 12 clubs. In their first year, under head coach Sam Vincent, the Flyers compiled the best regular-season record in the D-League, and they currently bill themselves as last year’s “regular-season champions,” which is slightly misleading. They fell short in the playoffs, losing at home to the Albuquerque Thunderbirds in the championship game. Even so, the Flyers were an immediate success story, by league standards. Vincent was hired as an assistant for the Dallas Mavericks, and leading scorer Ime Udoka went on to play for the Nigerian national team at the World Basketball Classic. After that he was signed by the Portland Trail Blazers and has become a starter on a rebuilding team.

Most of the other Flyers from that season have also moved on; 6’7” swingman Martell Webster is also with the Blazers, while 6’5” shooting guard Kelenna Azubuike signed on with the Golden State Warriors. Of last year’s Flyers, only Australian center Luke Schenscher and power forward Ndudi Ebi have returned. The lack of stability poses a challenge for Coach Moncrief. This became painfully clear in a March 2 game against the Colorado 14ers. The Mavs’ call-ups had taken away two of the Flyers’ mainstays: Barea, a Puerto Rican point guard whose scorer’s mentality (27 points per game) doesn’t prevent him from distributing the ball effectively (7.8 assists per game, second in the league), and Mensah-Bonsu, a lanky forward whose slashing drives to the basket make him Fort Worth’s most eye-catching player. The Flyers’ offense suddenly looked rudderless, and against one of the D-League’s top teams, the Flyers were blown out, 112-97. It was their seventh loss in nine games and a brutal postscript to a 1-4 road trip.

Replacing called-up players is a high priority. “Scouting is a crucial part of success,” said Michael Schmidt, a reporter for the basketball news web site Draftexpress.com, who can reasonably lay claim to being the foremost expert on the fledgling minor league. “Fort Worth is one of probably five teams that can find players who can step in and fill their roles,” he said. “If you look at the standings, you can see which teams can scout.” This job, which Moncrief agrees is difficult, falls to the coaching staff. To step in for their missing power forward, the Flyers re-signed Ebi, who is less explosive than Mensah-Bonsu and more of a post-up threat. Having spent the first part of the 2006-07 season without a team, Ebi was brought back because he’s a known quantity for the Flyers. Also returning is willowy 6’7” small forward Jeremy Richardson, who has shuttled back and forth this year between the Flyers and the NBA (two 10-day stints with the Atlanta Hawks and one with the Trail Blazers). “You can’t always try out new people,” Moncrief said in a resigned tone. “Our team is our team.”

Two days later, a game against the Tulsa 66ers turns out to be a much-needed spirit lifter. The 66ers roost near the bottom of the league standings and have been bitten by the same call-up bug as Fort Worth. Although they’ve got a size advantage on the Flyers, the Oklahoma players persist in going for three-point shots they can’t make (8-for-30 from beyond the arc), creating long rebounds that sail into the hands of the Flyers’ perimeter players, creating fast-break opportunities galore for Fort Worth. The Flyers coast to a 110-95 win, behind 23 points from both Corey Santee, a streak-shooting former TCU point guard, and Anthony Terrell, a gnarly rebounder with an unexpectedly soft touch around the basket. The victory kicks off a five-game winning streak, something the Flyers desperately need in their neck-and-neck race with the Dakota Wizards and Sioux Falls Skyforce for the lead in the D-League’s Eastern Division. The wins also help the individual Flyers in their continuous effort to catch major-league eyes. That hope for a call-up is the key factor keeping many D-League players in the States, when they could be making tons more money overseas.

Two days later, a game against the Tulsa 66ers turns out to be a much-needed spirit lifter. The 66ers roost near the bottom of the league standings and have been bitten by the same call-up bug as Fort Worth. Although they’ve got a size advantage on the Flyers, the Oklahoma players persist in going for three-point shots they can’t make (8-for-30 from beyond the arc), creating long rebounds that sail into the hands of the Flyers’ perimeter players, creating fast-break opportunities galore for Fort Worth. The Flyers coast to a 110-95 win, behind 23 points from both Corey Santee, a streak-shooting former TCU point guard, and Anthony Terrell, a gnarly rebounder with an unexpectedly soft touch around the basket. The victory kicks off a five-game winning streak, something the Flyers desperately need in their neck-and-neck race with the Dakota Wizards and Sioux Falls Skyforce for the lead in the D-League’s Eastern Division. The wins also help the individual Flyers in their continuous effort to catch major-league eyes. That hope for a call-up is the key factor keeping many D-League players in the States, when they could be making tons more money overseas.

Average salaries here are $20,000 for six months, plus full health benefits and free league housing. (The Flyers players live in a gated apartment complex in Hurst.) Compare this with the situation of Devin Green, a point guard who played for the Los Angeles D-Fenders in December 2006. He left the D-League to play for the defending champions of the German league, RheinEnergie Köln, signing a contract reportedly worth $150,000 over the first five months of 2007. And Santee, who joined the Flyers this year after playing a season for another German team, reported that some of his teammates were making $1.5 million a year — tax-free, for non-German citizens. For D-League ballers, though, the dream of making it to the NBA is worth the sizable financial hit. “An NBA scout can go from Austin to Fort Worth to Tulsa and see many more games in a much shorter space of time than if he’s traveling around Europe,” said Nicholson, the Flyers president.

This line is repeated by everyone from league officials to the players themselves, and Schmidt said it’s pretty much true. “There were about 50 NBA executives at the D-League All-Star Game,” he said. “There are still a few teams where the decision-makers are reluctant to use [the D-League], but I’d say 20 to 25 of them see it as a viable option for developing talent.” Under this system, the Mavericks, 76ers, and Bobcats, with which the Flyers are affiliated, can sign players to contracts, send them down to the Flyers for seasoning, and call them back up as needed. “Assigned” players such as these are paid NBA salaries whether they’re playing for the parent team or the D-League and can be sent down only twice before the parent team has to sign them to an NBA contract and carry them on the roster for the rest of the season.

Non-assigned players get one-year contracts with the league. They don’t have assurances from a parent team, and they’re certainly not being paid NBA money. However, they can be signed to 10-day contracts with any NBA team, as under the old CBA system. Players with local ties to a D-League market can be “allocated” there, as Santee is. For the Americans in the D-League, the big-time appears tantalizingly close, especially in Fort Worth where the Mavericks are seemingly next door. Sticking close to home has other rewards, too. Playing in the town where he played his college ball, Santee said, “It’s a blessing to come out [at Flyers games] and see purple jerseys in the stands.” The comforts of home go beyond sentimental ones for some players. Horror stories make the rounds about leagues in Russia, for instance, where paychecks sometimes arrive late or not at all. Indeed, Thomas, who previously played for the Latvian team BC Ventspils, confirmed that his old club would hold paychecks for days when management wasn’t satisfied with a player’s performance.

Non-assigned players get one-year contracts with the league. They don’t have assurances from a parent team, and they’re certainly not being paid NBA money. However, they can be signed to 10-day contracts with any NBA team, as under the old CBA system. Players with local ties to a D-League market can be “allocated” there, as Santee is. For the Americans in the D-League, the big-time appears tantalizingly close, especially in Fort Worth where the Mavericks are seemingly next door. Sticking close to home has other rewards, too. Playing in the town where he played his college ball, Santee said, “It’s a blessing to come out [at Flyers games] and see purple jerseys in the stands.” The comforts of home go beyond sentimental ones for some players. Horror stories make the rounds about leagues in Russia, for instance, where paychecks sometimes arrive late or not at all. Indeed, Thomas, who previously played for the Latvian team BC Ventspils, confirmed that his old club would hold paychecks for days when management wasn’t satisfied with a player’s performance.

Many graduates from the old CBA went on to become solid — if not usually star-quality — players for the NBA, but the coaches who cut their teeth there were among the greatest in the game, including Phil Jackson, Flip Saunders, and George Karl. The D-League seems poised to do the same. “It’s a fantastic place to develop coaches,” Schmidt said. “Moncrief is definitely head coaching material. He doesn’t sacrifice winning for player development like some other coaches do.” And thus far, the front office seems to be giving him the support he needs. Nicholson wouldn’t comment on how well the team is doing financially, but the crowds are healthy by D-League standards. Schmidt said the Flyers are probably in the league’s upper third in terms of attendance, though that’s impossible to verify, since some D-League teams don’t release attendance figures. “The California teams have not caught on,” Schmidt said. “The best-attended games are [those played by] the old CBA teams that already have established fan bases.”

In the end, what makes D-League games an appealing entertainment option isn’t just the low prices (cheapest seats are $10) or the endless rounds of promotions and giveaways conducted during the games. It’s the blue-collar work ethic shown by the personnel league-wide, who are all trying to make it to the next level, whether it’s the young game officials training to be NBA referees or the Flyers’ dance team, called the Fort Worth Fly Girls, two of whose members were called up to the Dallas Mavericks’ dance squad in midseason. This same ethic emanates from the athletes, driven by the prospect of an NBA contract and the tangible examples of players such as Udoka and the Charlotte Bobcats’ Matt Carroll, both former D-League guys now flourishing at the NBA level. “Our players hustle from whistle to whistle,” Nicholson said. “They don’t take plays off. They live for this stuff.” Yet the Flyers have more going for them than just scrappiness. Their composure in tight situations would do many an NBA team proud — perhaps another proof of Moncrief’s influence. In a March 24 game against the Austin Toros, the Flyers are red-hot and go into halftime with a 59-38 lead. But the Toros locate the basket in the third quarter, and with just over two minutes left, it’s a tie game. After some admittedly questionable foul calls against the Flyers, the crowd goes after the refs verbally, and one screamer sitting courtside draws a warning from the security staff. The audience may be small, but they rain cheers and boos onto the court with the same fervor as NBA and college fans and generate the same kind of intense, crackling atmosphere as they urge the home team to hang on.

In the end, what makes D-League games an appealing entertainment option isn’t just the low prices (cheapest seats are $10) or the endless rounds of promotions and giveaways conducted during the games. It’s the blue-collar work ethic shown by the personnel league-wide, who are all trying to make it to the next level, whether it’s the young game officials training to be NBA referees or the Flyers’ dance team, called the Fort Worth Fly Girls, two of whose members were called up to the Dallas Mavericks’ dance squad in midseason. This same ethic emanates from the athletes, driven by the prospect of an NBA contract and the tangible examples of players such as Udoka and the Charlotte Bobcats’ Matt Carroll, both former D-League guys now flourishing at the NBA level. “Our players hustle from whistle to whistle,” Nicholson said. “They don’t take plays off. They live for this stuff.” Yet the Flyers have more going for them than just scrappiness. Their composure in tight situations would do many an NBA team proud — perhaps another proof of Moncrief’s influence. In a March 24 game against the Austin Toros, the Flyers are red-hot and go into halftime with a 59-38 lead. But the Toros locate the basket in the third quarter, and with just over two minutes left, it’s a tie game. After some admittedly questionable foul calls against the Flyers, the crowd goes after the refs verbally, and one screamer sitting courtside draws a warning from the security staff. The audience may be small, but they rain cheers and boos onto the court with the same fervor as NBA and college fans and generate the same kind of intense, crackling atmosphere as they urge the home team to hang on.

Through all this the Flyers do not panic or lose their cool, and Thomas, Terrell, Richardson, and center Deji Akindele all chase down loose balls, block shots, and move without the ball on offense to shake off their defenders. Their efforts give Fort Worth a small lead, which is cut to two points by an Austin basket with less than two seconds left. There is no timeout called, and Thomas steps up to inbound the ball. He looks like he’s in trouble, with Toro defenders blanketing him and his nearby teammates, but then Thomas’ eyes go wide as he spots a white jersey in the distance, and he heaves the ball the length of the court to an unguarded Terrell underneath Austin’s basket. With no one else even in the frontcourt, Terrell dunks the ball as the buzzer sounds, giving Fort Worth a 113-109 win. The crowd sends up a mighty roar, and the Fly Girls take the court to dance to Kool & The Gang’s “Celebration.” Amid all this, it’s easy to feel that this hard-working squad and their quietly driven coach are both a small step closer to their goals.

You can reach Kristian Lin at kristian.lin@fwweekly.com.