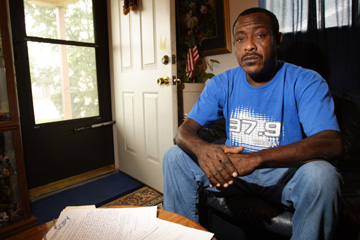

When Waxahachie police officers burst into Allen Nelms’ house in the early hours of April 28, they found him in his bedroom.

With weapons drawn and flashlights in his face, officers ordered him to the ground. And when he started to roll away from them, they fired, hitting him three times with their Tasers. Nelms’ crime, apparently, had been getting sick. When Nelms, 52, went into what he calls a diabetic seizure that morning, his fiancée recognized what was happening and called 911. But she has health problems of her own that make her words hard to understand, and the initial police report shows that officers went to the home in response to a “911 hang-up.” Still, she went out to the driveway, Nelms said, to flag down officers and tell them that Nelms, who also suffers from rheumatoid arthritis, needed paramedics’ help. Despite her explanations, Nelms said, the officers drew their weapons, “kicked in my door,” found Nelms lying on the bed, “and ordered me to get on the ground.”

With weapons drawn and flashlights in his face, officers ordered him to the ground. And when he started to roll away from them, they fired, hitting him three times with their Tasers. Nelms’ crime, apparently, had been getting sick. When Nelms, 52, went into what he calls a diabetic seizure that morning, his fiancée recognized what was happening and called 911. But she has health problems of her own that make her words hard to understand, and the initial police report shows that officers went to the home in response to a “911 hang-up.” Still, she went out to the driveway, Nelms said, to flag down officers and tell them that Nelms, who also suffers from rheumatoid arthritis, needed paramedics’ help. Despite her explanations, Nelms said, the officers drew their weapons, “kicked in my door,” found Nelms lying on the bed, “and ordered me to get on the ground.”

When a protesting Nelms tried to comply, he said, and rolled to one side to get off the bed, “they tasered me on my side, and when I flipped over, they shot me two more times — zap, zap, zap!” When the police were finished, Nelms’ fiancée said, they came out of the bedroom laughing. Nelms was never arrested or charged with any crime. The story is making the rounds on the internet, among those who keep up with what they see as Taser outrages and abuses. Taser cases in this state have even made it onto a documentary on “less-lethal” weapons, put together by German filmmakers. But Nelms’ tasering isn’t at the top of the list of recent Taser-related horror stories from Texas. That spot belongs to Johnny Lopez of San Angelo, a mentally disturbed man who had poured gasoline over himself on June 18. Police who’d been called to the scene couldn’t get him under control — and so they tasered him. The gasoline ignited — though police have said they don’t know what ignited it — and Lopez was fatally burned.

Nor are those the only recent complaints about Taser use and alleged abuse in Texas. In Fort Worth, two employees of John Peter Smith hospital filed suit in May over an incident two years earlier in which they allege that a Fort Worth police officer, who had just un-cuffed a mentally ill woman, ignored the mental health workers’ statements that they had the woman subdued and tasered her not once but twice — resulting, according to the lawsuit, in one of the hospital workers being shocked as well and the other being thrown against the wall by the jolt. According to the lawsuit, the two workers have suffered continuing ill effects, including seizures and memory loss. In San Antonio, Tasers were introduced to police only about six months ago, but already there has been one death of a person hit with the weapons’ electric jolt. The stories are part of a larger pattern of seemingly Taser-related deaths and injuries that have drawn protests and cries for action across the country — including many cases in which the victims were obviously mentally disturbed, and whose only apparent crime may have been something like running down the street naked.

But if Texas seems to be drawing some of the worst allegations of Taser abuse, it is also a state that fits into the other side of the Taser equation: that of a growing number of cities and states where activists, elected officials, and some law enforcement groups, are pressing police agencies to re-examine their use of the weapon that has been touted as a way to reduce deaths and serious injuries of both officers and citizens, but whose use has been quickly followed by death for hundreds of people around the country. “What they’re finding is, Taser usage hasn’t reduced the amount of violence on the street, doesn’t necessarily result in more convictions, and does not help control otherwise hard-to-control situations. And there are police who have repeatedly tasered, and therefore permanently injured, people because they don’t have the proper training — if there is such a thing as proper training. … It’s clear that Tasers are being used inappropriately — if there is any use you could call appropriate.”

The speaker is Maida Asofsky, Houston regional director for the American Civil Liberties Union in Texas. Houston — along with Austin — is one of the Texas cities where Taser-related deaths and alleged abuses have caused the most uproar. An NFL football player, members of two indie rock bands, a college student visiting from Georgia, and a man who took too long to find a place to pull over for a routine traffic stop are among the growing list of people who have been tasered by police in Houston under controversial circumstances. An analysis by the Houston Chronicle found that, in 95 percent of the cases where Houston officers used Tasers, those on the receiving end of the 50,000-volt charge were unarmed, and that in the first 900 of 1,000 Taser uses, charges either were never filed, dropped by prosecutors, or subsequently dismissed by the courts. The questions led Houston City Controller Annise D. Parker, an elected official, to begin an audit of the HPD’s Taser program, looking at training issues, use policies, and medical complications for victims, among other things. A spokeswoman for Parker said this week that the audit group is trying to wrap up the study, and that it might be ready by the end of August.

In San Antonio, said Debbie Russell, who heads the Texas ACLU’s Taser hotline, a broad coalition is organizing to try to affect Taser policies used by the police department. And in Austin, where there have been a number of high-profile Taser cases, Russell said that civil libertarians and Taser activists are encouraged by the appointment of a new police chief whom she hopes will institute changes in Taser use policies there. Two years ago, she said, “we started a campaign” on abuse of the electronic pulse weapons, that may have “embarrassed them enough to get them to do the right thing.”

Houston and Fort Worth legislators both filed bills in this year’s session to force police agencies to rethink the use of the electronic weapons. The various bills would have instituted a moratorium on Taser use pending further study, required training, limited circumstances in which the weapons could be used, required police to keep more records on the weapons’ use, and mandated medical care for those who receive shocks. None of the bills passed — but some of the safeguards the legislation envisioned are actually being adopted by some police agencies. Not everybody is as worried about Tasers as Russell and the ACLU, of course.

Mary Ramos of Houston, national civil rights co-chair for LULAC, said that, after she and others in Houston did an intense study of Tasers for more than a year, including taking training that police officers receive and riding with officers, she went to the national LULAC board last October with a proposal that the group support the use of Tasers. “We support Tasers. The national board voted for it, the state board voted for it,” she said. Even though some other LULAC members in Texas have expressed concerns about the weapons, she said, those statements “were made by someone who didn’t know where LULAC stood.” “I’d much rather them taser my people than shoot them with a gun,” she said. People like Russell and Asofsky would prefer that neither happened, of course, and they believe that Tasers in some places have simply added to police violence, rather than replacing more dangerous gunshot wounds with “safer” Taser jolts. But Ramos is convinced. She said the Houston group studied close to 250 cases of Taser use by Houston police during that time. In at least 40 of those cases, she said, “I can tell you I really feel that Tasers saved lives — [cases] where police could have used a gun and shot that person but instead used a Taser.”

Mary Ramos of Houston, national civil rights co-chair for LULAC, said that, after she and others in Houston did an intense study of Tasers for more than a year, including taking training that police officers receive and riding with officers, she went to the national LULAC board last October with a proposal that the group support the use of Tasers. “We support Tasers. The national board voted for it, the state board voted for it,” she said. Even though some other LULAC members in Texas have expressed concerns about the weapons, she said, those statements “were made by someone who didn’t know where LULAC stood.” “I’d much rather them taser my people than shoot them with a gun,” she said. People like Russell and Asofsky would prefer that neither happened, of course, and they believe that Tasers in some places have simply added to police violence, rather than replacing more dangerous gunshot wounds with “safer” Taser jolts. But Ramos is convinced. She said the Houston group studied close to 250 cases of Taser use by Houston police during that time. In at least 40 of those cases, she said, “I can tell you I really feel that Tasers saved lives — [cases] where police could have used a gun and shot that person but instead used a Taser.”

Just north of Austin, police department leaders in Pflugerville had a revolutionary idea a couple of years ago: Study Tasers and talk to the community before deciding how to use them. It’s a course that may put the 29,000-population town ahead of many major cities. “We had a long, drawn-out process before we ever implemented [Tasers],” said Police Capt. Jim McLean, Pflugerville PD’s second-in-command. “We had a public forum first. … We said, ‘We want you to come out, we’re going to demonstrate the different force options our officers have.’ “ “We had all these people come in, we showed them bean-bag shotguns (another “less-lethal” weapon), we showed them different take-down techniques we use, different self-defense tactics. Then we went to the Taser. One of our lieutenants, they actually shot him with it.” After the forum, McLean said, police officials got feedback from citizens and “kept that in mind as we drafted policies and procedures.” The result is a set of parameters that, if followed, could conceivably prevent many of the situations that have ended in deaths and severe injuries in other cities.

Whenever a Pflugerville officer uses a Taser, he or she is required automatically to contact emergency medical personnel “and have them en route, whether it looks like they need it or not,” McLean said. There are rules on not using the pulse weapons on people who are too old, too young, or obviously pregnant. Any time an officer uses the Taser, an administrator is sent out, and an internal affairs investigation is automatically initiated, “whether the person [who’s been tasered] complains about it or not. “We basically treat it as a crime scene of a more serious magnitude,” McLean said. “In the beginning it scared our officers. … We have told [them], we take this very seriously. We are going to see if our policy works, if the training works, if there is adequate supervision.” Granted, Pflugerville is a different kind of place for law enforcement than, say, Houston. In the year or so since the department handed out its eight Tasers (they go to whichever of the department’s 54 officers are on duty), the weapons have been used twice. “Our guys have done extremely well,” McLean said, “I’m proud of them for the times they used it.” Both occasions involved chases of fleeing suspects, and one included a scuffle in which an officer ended up hitting the ground in the middle of a road with traffic on it. In both, McLean said, “they weren’t quite justified in using deadly force, but were real close to it.”

The department also made one other major decision: to equip each of its Tasers with a camera, at a cost of $400 each. That’s “one of the thing we were … very fervent about, having cameras,” McLean said. “Being right next to Austin and with all the publicity they’ve received [about alleged abuses of the weapon], we wanted to have something just a little more to show we’re doing things right.” They don’t work quite the way police officials had hoped, though: Because they don’t start running until the safety is off, the cameras for the most part don’t record the situation leading up to the officer pulling the weapon out. That’s something his department would like to see changed in future versions of the equipment, McLean said. On the other hand, he said, in several cases where officers have pulled the Tasers but not used them, the cameras “have captured incredible video and audio, of things happening that our car video wasn’t able to catch.” The Pflugerville captain said his department’s policies aren’t that much different from the recommendations of Taser International, which makes the weapons. “We just took it a little further to make sure the community trusted us in what we were doing,” he said.

Community trust in what Fort Worth police officers were doing with the electronic weapons might not have been too high about a year ago. Four people died after being tasered, including architect Eric Hammock, who was hit at least 25 times by two officers in a nine-minute period, for a total of more than two minutes of shock, after police pursued him because he drove off from a private parking lot he had entered and refused to stop when an off-duty officer approached. If the incident happened today, Hammock might have had a better chance of surviving. In the intervening year, the police department here has made a number of changes in its policies regarding Tasers. For one thing, departmental policy now bans multiple officers from shocking the same suspect, in most cases. The policy also now requires medical help to be summoned anytime a person is jolted more than twice — or in any situation in which the person who has been shocked appears to be under the influence of drugs or is having breathing problems. If a person is already showing signs of drug use, mental instability, or medical distress, officers are directed to get medical attention to the scene even before a Taser is used, if that’s still the best method of bringing the person under control. And Tasers have been moved up in the department’s “use-of-force” list, meaning it is considered at least a slightly more serious weapon than it had been previously.

Fort Worth officers are also told that, in most circumstances, they shouldn’t use the Tasers on anyone under 11 years of age or over 70, or who is visibly frail or pregnant. It’s not an outright ban, said Lt. Paul Jwanowski, who oversees the department’s executive services bureau, which includes training, “but what we’re telling them is, you’d better have a damned good reason for using it” on anyone in those groups. Like Pflugerville, Fort Worth’s policy also now requires a supervisor to be sent to the scene anytime someone is tasered. And — a rule that conceivably could have saved Johnny Lopez’ life — police here are now discouraged from shooting their electronic weapons in any situation “where there is the presence or possibility of concentrated flammables or combustible liquids,” department spokesman Lt. Dean Sullivan said. The department has also changed its pepper spray, he said, from a type that is alcohol-based to one that is water-based, to avoid similar problems.

Sullivan said the department will continue to review studies and other information about Tasers and will adjust their policies accordingly. “We continue to review them even to this date,” he said. “I don’t know what to say about those four unfortunate circumstances” — the deaths — “but those were part of our consideration and review.” Had the tighter policies been in force two years ago, on the night that Officer Brent Halford was escorting a woman from the JPS hospital emergency room to the psychiatric ward, it still might not have made much difference. Policies don’t always stop people who are angry and have weapons to hand — though they can make them think harder about the consequences. According to Fort Worth Civil Service Commission records, Halford and another officer had delivered the woman to the ward. Halford was taking off her handcuffs when she began to pull away, because she said the cuffs were hurting her wrists. She’d had heart surgery, she said, and as he brought her arm behind her back to uncuff it, that hurt her chest. When she pulled away, the records say, she “caused a minor laceration” to Halford’s left hand from the cuffs. Then she whacked him with one hand on his body armor. JPS medical technician Richard Banda and psychiatric tech Gerald Kern grabbed her and placed her face-down on a bed, the commission found, “eliminating her from any further threat of violence.”

Sullivan said the department will continue to review studies and other information about Tasers and will adjust their policies accordingly. “We continue to review them even to this date,” he said. “I don’t know what to say about those four unfortunate circumstances” — the deaths — “but those were part of our consideration and review.” Had the tighter policies been in force two years ago, on the night that Officer Brent Halford was escorting a woman from the JPS hospital emergency room to the psychiatric ward, it still might not have made much difference. Policies don’t always stop people who are angry and have weapons to hand — though they can make them think harder about the consequences. According to Fort Worth Civil Service Commission records, Halford and another officer had delivered the woman to the ward. Halford was taking off her handcuffs when she began to pull away, because she said the cuffs were hurting her wrists. She’d had heart surgery, she said, and as he brought her arm behind her back to uncuff it, that hurt her chest. When she pulled away, the records say, she “caused a minor laceration” to Halford’s left hand from the cuffs. Then she whacked him with one hand on his body armor. JPS medical technician Richard Banda and psychiatric tech Gerald Kern grabbed her and placed her face-down on a bed, the commission found, “eliminating her from any further threat of violence.”

But Halford wasn’t satisfied, apparently. Pulling his Taser, and while the medical personnel protested and tried to stop him, he reached over Kern and shot the woman with the Taser. Kern felt the shock as well, he told the commission, and it caused him to stumble and fall against the wall. Banda said he, too, felt the shock. The nurses and a doctor yelled at him to stop, but Halford, the commission found, waited for his Taser to recharge and then shocked her for five more seconds.

Halford “clearly overreacted,” the commission found. He was suspended for 10 days. In the two years since the JPS incident, Fort Worth’s policies — and the way the department views Tasers — seem to have changed substantially. Many other police agencies — and not just the ones in small Texas towns — appear to still take the earlier view of the electronic weapons, using them like low-level persuaders, to get prisoners to move their feet or get out of a car, or persuade mentally unstable people to “settle down.” Or, as in Allen Nelms’ case, to convince a sick man in a dark bedroom to get on the floor.

In that case, Waxahachie police have released only a one-sentence report on the case and wouldn’t comment on it even for the local Waxahachie Daily Light. Nelms said the officers told him he was shocked because he “launched” at the multiple officers who surrounded his bed. “They pulled at me like a puppet,” this way and that, until the Taser barbs were removed by paramedics, Nelms said.

Since that night, he said, he’s heard from the police only once. “A review regarding your written complaint … was conducted,” says the four-line letter dated May 9. “After careful consideration of your allegations, we have found that the officers were within our departmental policies regarding the less than lethal force option (TASER) on you during an event at your residence.” Two years ago, Taser International’s position was that the low-amperage current of its weapons “prevents Tasers from causing permanent damage on suspects.” There were no warnings about how to avoid permanent injury or situations in which injury or death might occur. Now, the web site carries about four pages of product warnings for law enforcement. “Can cause injury” is one of the bullet points beside a stylized warning figure of a human being shocked. The company’s safety warnings advise police to avoid “torturous” misuse of the weapons. Officers are told that significant injuries can occur if Tasers are shot into the throat, genitals, or eyes or areas where victims have pre-existing injuries. The Taser “can ignite explosive materials,” the page says. And prolonged or continuous “exposure” to a Taser’s discharge, in some people, “may contribute to … stress and associated medical risks.” Extended or repeated Taser “exposures” should be avoided, the company warns. “It is conceivable that the muscle contractions [caused by the shock] may impair a subject’s ability to breathe.” And repeated electrical stimuli can cause seizures. “Strain” injuries — hernias, ruptures, tears … to soft tissue” could also occur, the web site says. Use of a Taser could “cause marks … and/or scarring that may be permanent.”

The web site warning also talks about “sudden in-custody death syndrome,” an odd phrase that suggests that the human body experiences something in police custody that it doesn’t under other circumstances. Steve Tuttle, the Taser vice president who acts as the company spokesman, apparently has his response down fairly pat for instances in which people have died following a Taser shock. “Until all the facts surrounding this tragic incident are known,” he was quoted in a 2005 New York Times story as saying, “it is inappropriate to jump to conclusions on the cause of Mr. Thomas’ death.” The death in question was that of Terrence Thomas, who died in New York Police custody. Just last week, Mr. Tuttle’s response was eerily similar, after a Denver man, found in his neighborhood behaving erratically, was hit with a Taser and died about an hour later. The Rocky Mountain News reported that, in an e-mail promoting his company’s “personal” Taser, Tuttle said, “Until all the facts surrounding this tragic incident are known, it is inappropriate to jump to any conclusions on the cause of this death.” Tuttle did not respond to e-mailed requests for comment for this story, and the company declined to provide any other representatives to comment.

Staff writers Peter Gorman and Jesseca Bagherpour contributed to this story.

You can reach Gayle Reaves at gayle.reaves@fwweekly.com.