The 120 or so people gathered at J. Gilligan’s Bar and Grill in Arlington recently were celebrating an early Christmas present. The party was hosted by the Downwinders at Risk, an environmental group based in North Texas, in honor of the recent appointment of Al Armendariz as regional administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, making him the top environmental official in Texas.

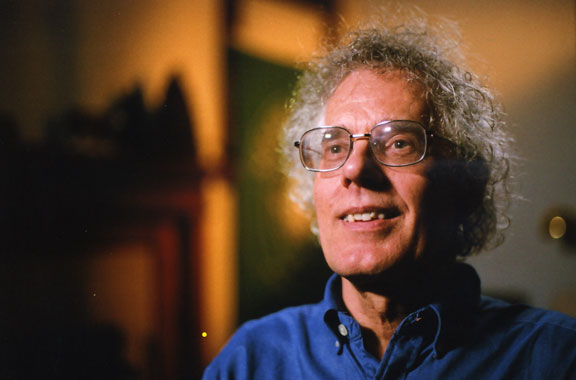

An Obama administration political appointment might seem like a peculiar occasion for a party, but as Fort Worth resident and Barnett Shale activist Jerry Lobdill put it, “Small victories have to be celebrated because we have so damn few of them.”

An Obama administration political appointment might seem like a peculiar occasion for a party, but as Fort Worth resident and Barnett Shale activist Jerry Lobdill put it, “Small victories have to be celebrated because we have so damn few of them.”

Armendariz’ selection is one of the most salient signals that the Obama administration and the EPA are getting serious about fixing the myriad environmental calamities in this state. But as environmental activists and legislators point out, fixing Texas will be no small task.

Many critics of the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality believe the agency has favored industry over public health for many years, to the detriment of Texas air and water quality and safety concerns. But the newly restructured EPA, with Lisa Jackson as administrator, has emerged as one of the most aggressive regulatory agencies in the Obama administration, and the effect on Texas could be profound.

In a state where the overall environmental picture is one of the grimmest in the nation, the EPA is being particularly assertive, insisting that the state tighten its pollution rules. The federal agency has threatened to void some of the state’s air quality regulations, which it says break federal law. The EPA recently undid some George W. Bush-era regulatory changes that relaxed rules on refinery emissions. The agency is also examining the effects of gas drilling on air quality. New rules for oil and gas emissions that would affect the Barnet Shale area are expected to be developed within the next 18 months.

In other words, insiders say, the EPA is going to clean house whether state officials like it or not. Former TCEQ commissioner Larry Soward, who favors stricter regulation, said an EPA official recently told him, “The state of Texas can step up, or the EPA will step in.”

The significant changes that the EPA has proposed in how Texas regulates potential industrial polluters has stirred up political opposition. Because much of TCEQ’s role involves enforcement of federal environmental law, the state agency could be forced to change how it does business or face the specter of federal intervention, which, for Texas conservatives, is just as horrifying as any campfire ghost story.

The EPA recently declared that greenhouse gases are an air quality threat, adding them to the list of harmful – and therefore regulated – pollutants. The decision could lead to the first-ever federal limits on greenhouse gases from power plants, cars, petrochemical plants, and other sources.

Currently 21 Texas counties are considered air pollution non-attainment counties – that is, their air is dirty enough that it violates the Clean Air Act – including Tarrant and Dallas. Though areas like North Texas and Houston have made some headway in cleaning up ozone, the improvement has not been fast enough to meet federal standards.

And the pollution guidelines are about to get stricter. Next Monday, Dec. 21, the EPA will propose lowering the maximum allowable concentration of ozone from 75 to 70 parts per billion. At least one environmentalist believes that more than 20 additional counties in Texas will be unable to meet the new standards.

Texas’ overall water quality is also ranked among the worst in the country, and environmentalists say that toxic dumping and mercury emissions from industrial plants is to blame. Ten percent of the nation’s mercury emissions come from plants in Texas, according to Clean Water Action, an environmental group. Mercury is linked to autism in children and heart attacks in older people.

Even the notoriously industry-friendly TCEQ is starting to take notice, after a study by an independent environmental research organization on the effects of gas drilling on the city of DISH found that gas compressor stations are emitting high levels of poisonous chemicals.

In Texas, opposition to the EPA’s toughened stance starts with Gov. Rick Perry, who is on the record as a climate change denier. He recently wrote to Jackson, urging her to withdraw the EPA’s ruling on the dangers of carbon dioxide. Perry and other critics of the EPA are worried about federal intrusion in state matters and about job losses due to what they see as federal over-regulation.

“The unelected bureaucrats at the EPA have effectively and unilaterally ended any honest debate on this vital issue,” Perry said on his web site.

TCEQ board chairman Brian Shaw issued somewhat ambiguous congratulations to Armendariz on his appointment, possibly foreshadowing the battle to come.

“I hope Dr. Armendariz recognizes that this position is too important to be used as a podium for environmental activism,” he said. “I urge Dr. Armendariz to use sound science in his decisions.”

Armendariz, a 39-year-old El Paso native, recognizes that his job isn’t going to be easy, but he hasn’t lost sight of what he’s working for.

“I’m here to make a difference, a real difference, in people’s lives when it comes to the air they breathe and the water they drink and the environment as a whole,” he said.

Armendariz, a former engineering professor at Southern Methodist University, has been openly critical of state and federal regulators for allowing industry to run roughshod over the Clean Air Act. He’s published numerous articles and papers, testified as an expert witness, and advised several area environmental groups on the damage being done by cement kilns, power plants, toxic waste dumping, and countless other hazards. In each case he’s been critical of the TCEQ.

Armendariz’ path from engineering professor to one of the most prominent environmental officials in the country was started by the Downwinders, who hired him as a consultant on Midlothian cement kiln emissions. In 2005, a plant owned by Holcim Cement got into trouble over permit violations and agreed to pay for an independent scientist who would monitor their activity and observe on-site testing. The Downwinders selected the SMU professor, who had also worked as an air quality compliance engineer for a natural gas utility.

Armendariz’ path from engineering professor to one of the most prominent environmental officials in the country was started by the Downwinders, who hired him as a consultant on Midlothian cement kiln emissions. In 2005, a plant owned by Holcim Cement got into trouble over permit violations and agreed to pay for an independent scientist who would monitor their activity and observe on-site testing. The Downwinders selected the SMU professor, who had also worked as an air quality compliance engineer for a natural gas utility.

According to Jim Schermbeck of Downwinders at Risk, Armendariz became their unofficial technical advisor.

“What happened was, he went down to start doing this monitoring and found that a lot of the cement plants didn’t have the pollution control equipment that he was used to dealing with,” Schermbeck said. “He realized that the cement industry in North Texas isn’t very sophisticated, and he had an intellectual curiosity as to why that was and what it would take to bring them up to par.”

Armendariz advocated a filtering system for cement plants called selective catalytic reduction (SCR), an industrial boiler setup that reduces emissions of some harmful chemicals by up to 95 percent. He published multiple works on the subject and quickly became regarded as a national expert on cement plants.

In 2007, while cutting his teeth on cement, so to speak, he went to Austin to testify on behalf of a bill that proposed a pilot test of SCR technology be done at state expense at one of the cement plants.

The bill passed the Senate but died in a House committee. Despite that, the experience provided important political lessons for Armendariz.

“That was a really big turning point for him in terms of educating himself about how environmental policy in Texas got made or didn’t get made,” said Schermbeck. “I don’t think he had any experience with policy-making before – to that degree – and he liked [the experience] a whole lot.”

Afterward, he wrote a series of articles and papers critical of the EPA-approved TCEQ plan to bring state air pollution levels down to the federally mandated level. He told an incredulous Texas House Environmental Regulation Committee that the plan wouldn’t work, and he was proven correct. The plan was supposed to get Texas areas in compliance by last summer and failed to do so.

Standing up to the state and the feds made Armendariz something of a rock star in environmental circles. The Environmental Defense Fund, a nonprofit environmental advocacy group, hired him to study the Barnett Shale, and he produced a damning report on emissions from the shale operations. He concluded that in nine counties, including Tarrant and Dallas, gas drilling produced 112 tons of pollution a day, compared with 120 tons per day from automobiles. He also suggested several ways to mitigate the pollution, including requiring “green completion” of wells to prevent gas from being vented.

From there he became an expert witness for many groups trying to fight potentially polluting projects, whether it was coal plants in Corpus Christi, gas drilling in North Texas, cement plants, or anything else.

“He was waiting to do this, I think,” said Schermbeck. “There was a part of him that was a policy wonk that hadn’t been given a chance to bloom.”

Now on his third week on the job, after taking over for Bush appointee and former Arlington mayor Richard Greene, Armendariz said that one of the most difficult parts of the transition into his new role has been the number of issues he has to focus on at once.

“When I was at SMU, even when I was doing environmental work for local community groups, I could often focus on a single issue for many months or many years,” he said. “Whereas here, because of all of the things the agency does, I’ve got to lead on many issues.

“Now I’m looking at these issues on a very big-picture level, going from program to program,” he said. “There are issues of priority that come up, including the Texas air program, which still demands a lot of my time.”

Texas ranks the worst in the country in carbon dioxide pollution from power plants, according to an analysis of government data performed by Environmental Texas, an air quality advocacy group. The study also found that 51 of Texas’ 116 power plants were built before 1980, and the Martin Lake Steam Electronic Station near Dallas alone produces the same amount of global-warming pollution in a year as 3.8 million modern cars.

A recent study conducted by the U.S. Energy Information Administration concluded that if Texas were a separate country, it would rank seventh in the world in terms of carbon dioxide emissions.

On the national level, the EPA has already issued tough new fuel-efficiency standards for automobiles in an effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. By 2016 new cars will have to provide an average fuel efficiency of 36.5 miles per gallon. The agency has moved to regulate carbon dioxide emissions from power plants, kilns, and oil refineries; announced plans to set tougher limits on mercury emissions from coal- or oil-burning power plants; and held up dozens of permit applications for potential polluters. Sources said it’s not yet clear how the EPA initiatives will affect plans to build several new coal-fired power plants in Texas.

In Texas the EPA has announced its intent to disallow some rule changes relating to the state’s plan to comply with federal air quality standards, which would affect the TCEQ’s methods of licensing power plants.

One example is Texas’ “flexible permitting program,” which allows a plant to pollute in the short term as long as it complies with overall federal standards in the long term. Another is the “qualified facilities permit,” which allows operators to make changes at a plant without complying with rules requiring them to implement the latest technologies. Both those changes have reduced the public’s opportunity for comment and debate on permit applications.

One example is Texas’ “flexible permitting program,” which allows a plant to pollute in the short term as long as it complies with overall federal standards in the long term. Another is the “qualified facilities permit,” which allows operators to make changes at a plant without complying with rules requiring them to implement the latest technologies. Both those changes have reduced the public’s opportunity for comment and debate on permit applications.

The EPA proposal is intended to fix what many critics say is a broken system, and it’s a key element in bringing Texas urban areas back into compliance with the Clean Air Act, one of Armendariz’ top priorities.

“It’s not going to be overnight, but it’s not going to take many years either,” he said. “This is a very important issue to me and the staff. We’re hopeful in the short term we can work with the state of Texas so that they can develop a permitting program that complies with the federal program. I think we’ll get there.”

Armendariz said that many plants will have to re-apply because their permits were approved through a flawed process.

Armendariz and the state officials are also in a race against time. As the state scrambles to comply with existing standards under the Clean Air Act, the EPA is on the verge of raising the bar.

Under those stricter air quality standards, “The number of ozone non-attainment areas will possibly double, and the number of counties is going to jump,” said Neil Carman, director of the clean air program for the Lone Star Chapter of the Sierra Club.

One of North Texas’ major problems in complying with federal clean air law is that the Metroplex is downwind of so many noxious power plants in East Texas and coal plants in Central Texas.

“We’ve got to go after these power plants, and with someone like Armendariz as the regional administrator, he’s going to be talking about this problem with the EPA. I think he’s going to be very good,” said Carman.

Armendariz didn’t say whether the EPA has a plan specifically for Texas, but he did say that Jackson’s national priorities are also major priorities for the region.

“Some of her priorities include a renewed emphasis on children’s health, and also in environmental justice, to protect the most vulnerable communities – the communities along the fenceline of major industrial facilities,” he said. “She’s also placed a big emphasis on clean water, making sure that the waterways are cleaned up and that the drinking water is as clean as it should be, and [with] a big emphasis on green jobs and renewable energy.

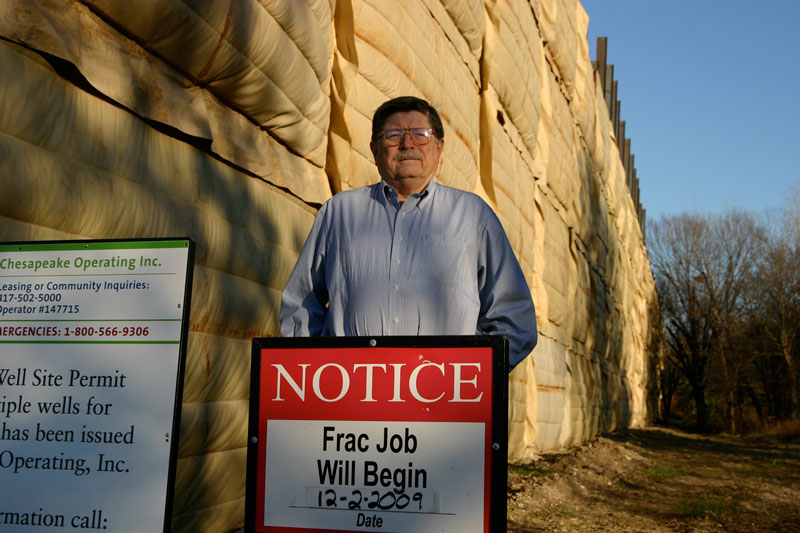

In Fort Worth, Mayor Mike Moncrief and the city council have bent over backward for the shale drilling industry, which has used Fort Worth like a guinea pig for the urban drilling experiment, raising many serious questions about the dangers of their operations to the health and safety of residents. Meanwhile, the mayor, who receives hundreds of thousands of dollars in annual income from oil and gas stock, is finally getting around to asking questions about the potential for pollution.

In the last six years, the mayor and council have mostly shunted aside reports and questions on the potentially damaging effects of gas drilling on the environment. One such report came from Armendariz himself last March, in which he concluded that gas drilling may produce more of some harmful pollutants than all of the automobiles in the Metroplex combined.

The Barnett Shale Energy Education Council, an industry-funded group, questioned Armendariz and his co-author’s work, and the city council and mayor rolled their collective eyes at the report.

“He hit the nail on the head with his analysis on the air, and he was treated terribly by the city manager of Fort Worth and the council,” said Lobdill. “They just ignored him because they don’t want to hear anything bad about the gas drilling business, and anybody who says anything bad is going to be marginalized. That’s what they tried to do with him.”

Recently, however, the council and mayor have changed their tune on the pollution caused by drilling. A study by the environmental engineering firm Wolf Eagle for the city of DISH found high levels of neurotoxins, such as benzene, in the air around residential areas near compressor stations. Some of the chemical levels exceeded 10 times the recommended levels for short-term exposure and could potentially lead to serious medical problems for residents.

The Fort Worth council commissioned a report similar to that done in DISH, and earlier this month, TCEQ sent engineer Keith Sheedy to answer their questions. Sheedy stammered and stumbled his way through a slide show, and he failed to answer the basic question as to whether drilling from the Barnett Shale is releasing harmful toxins into the Fort Worth air.

State Rep. Lon Burnam and activists such as Lobdill have called for a moratorium on drilling until the health hazards are fully understood.

According to Armendariz, the EPA is 18 months away from implementing tougher emissions standards for gas drilling as a result of lawsuits the agency settled with two Colorado environmental groups, which sued the agency for not updating the regulations.

Despite his earlier work, Armendariz, not surprisingly, now takes a more diplomatic public stance on the subject.

“The natural gas resources that we have in the region are an important source of energy and an important source of jobs,” he said, sounding rehearsed and deliberate. “The administration has placed an emphasis on finding new sources of energy, and I believe the Barnett Shale can be produced and used in a way that’s environmentally friendly.”

He said that he hopes industry and the state can work together to find a solution, though he did concede that if companies don’t comply with the new federal standards, he would be willing to “use the tools of the agency to protect public health.”

“What’s happened is that the Barnett Shale, up to this point, has not been as protective of the environment as it should have,” he continued. “I am hopeful that things will change.”

“What’s happened is that the Barnett Shale, up to this point, has not been as protective of the environment as it should have,” he continued. “I am hopeful that things will change.”

Despite their renewed optimism, Texas environmentalists recognize the road ahead is still cluttered with obstacles, the foremost of which is state government. Armendariz has been dropped into the middle of a political tug-of-war between the EPA and TCEQ. Many elected state officials see the federal agency’s appointment as a call to arms to protect states’ rights, and they view Armendariz as a soldier in Obama’s big-government army, determined to tell them how to run their state.

In a speech he gave in connection with filing for re-election, Perry took the opportunity to warn against what he called “government environmental intrusion,” which many observers believe was a direct shot at Armendariz.

“I think Perry fully intends to run for re-election [by] beating up on the federal government,” said Burnam. “He’s certainly did that all session long, and he hasn’t let up, and I don’t think he will let up. I think he’s got Al in his sights.”

Burnam, who was among those who lobbied Jackson on Armendariz’ behalf, realizes that progress might be slow. He believes that any measure that might force industry to change its ways will be met with defiance.

“It’s a huge hurdle because of the bias of both the current governor and the previous governor – the bias that has trickled down the agency since 1995 – has been to let industry get away with almost anything and everything,” he said. “That’s a huge cultural and institutional bias to overcome.

“TCEQ thinks everything can be accomplished by voluntary commitment from industry,” he continued. But, he pointed out, “if anything were going to be accomplished by voluntary commitment, they would have already done it.”

Soward, the former TCEQ commissioner, agreed. “Texas has taken the position that ‘We’re not going to change,’ and I think there will be some very difficult times ahead,” he said. “I think it is possible to find middle ground, but it’s going to take some attitude adjustments.”

Armendariz said he hasn’t had time to think much about the stiff political opposition he’s soon to face, because he has had his nose to the grindstone ever since he started the job. “These issues are being talked about by politicians,” he said. “It’s not something that I spend a lot of time thinking about.”

Schermbeck agrees that Perry’s office views Armendariz as a threat. He also pointed out that the EPA sees Perry as a problem in getting their agenda across.

“On the other side, in D.C., they see [Perry] as being a primary obstacle in doing what they need to do in terms of all kinds of agendas: global warming, toxic pollution,” he said. “Texas is the belly of the beast in terms of the petrochemical industry. A lot of the problems that the nation faces originate here.”

State Rep. Kelly Hancock, a Fort Worth Republican who sits on the House Environmental Regulations Committee, defends the job the state is doing.

“If you look at the state data … Texas has done a pretty a healthy job of reducing emissions,” he told Fort Worth Weekly. “In North Texas we’ve seen a steady decline in those [more dangerous] gases that we’re dealing with.”

Hancock and others believe that the EPA’s decision to toughen the ozone standards could cost many Texans their jobs. “Because they continue to change the level, they continue to change the goal for us, and what we need to do is to find ways to address the situation that don’t cost jobs and don’t negatively impact Texas,” he said. “We’ve done that, and we’ll continue to do that.”

In a press release, Perry said he is worried as well. “I am calling on the EPA to suppress the urge to regulate and include greenhouse gases in the Clean Air Act and find ways to unleash our economy, not strangle it,” he said.

“The EPA is making plans to re-interpret the federal Clean Air Act in ways that were never contemplated when this law was passed and will cripple the Texas economy,” he said. “The methods under consideration by the EPA will punish innovation, cost jobs, and drive investment out of Texas and overseas.”

Soward believes that the EPA will “make an example” of Texas if it does not comply with federal standards.

“Al Armendariz’ appointment is a telling sign to me that the EPA means business,” he said. “They chose an environmental activist who has been very critical of TCEQ’s air program, and I think the message is clear that Texas isn’t going to be allowed to draw a line in the sand like we have before.”

Armendariz said he plans to be sensitive to industry and states’ rights and would prefer that industry and the state make their own voluntary changes. But he also warned, “At the end of the day, I took an oath, and it’s my obligation to enforce federal law and to implement federal law, so I’ve got to make sure that the program we end up with meets federal requirements,” he said.

Karen Hadden, director of the SEED Coalition, an Austin-based environmental advocacy group, is one of many environmentalists who watched Armendariz testify in Austin.

Karen Hadden, director of the SEED Coalition, an Austin-based environmental advocacy group, is one of many environmentalists who watched Armendariz testify in Austin.

“He did not always get the respect that he deserves at the legislature. At least one of the members on the environmental committee” – Hancock – “was fairly rude toward him,” she said.

But Hancock said that he has no animosity toward Armendariz and that he is not skeptical regarding Armendariz’ past activism.

“I would say that we all make money one way or another. Activists get paid to be activists. They play a role out there, and I appreciate the job they do,” he said. “We’ve got to address the concerns of all of our constituents.”

Carman said that he does not believe the EPA would ever pull funding from TCEQ – for enforcing federal environmental laws – but pointed out that that’s a possibility if the state agency doesn’t comply. Armendariz, he said, holds the cards.

“Here’s the catch-22: If the state doesn’t follow what the Clean Air Act requires, the EPA could take the program over,” he said. “The state doesn’t want that, and industry doesn’t want that. Industry likes having TCEQ on the job because of what they’ve gotten away with,” he said.

“If TCEQ doesn’t want to play ball, the EPA could say, ‘We’re cutting off your funding immediately, and we’re taking back all of the authority,'” he continued. “That would be a huge embarrassment. They would have to fire 1,000 to 1,500 people immediately. I don’t think it will happen.”

As excited as many environmentalists are over the newly restructured EPA, they are also suffering from years of pent-up frustration over what they view as the indifference of environmental officials at every level of government – and they’re casting their own set of lofty expectations on Armendariz. Both his critics and his supporters believe that his appointment is proof that the Obama administration is serious about changing the way the environment is managed in Texas.

Schermbeck pointed out that in past Democratic administrations, such an appointment would have gone to someone with deep pockets who had given money to the party or had party connections. “It’s unusual to see an appointment like this that doesn’t have a lot of back-room deal-making going on,” he said. “He had nothing going for him except honest environmental advocacy. And that was enough, and I think that’s what everyone is so excited about.”

Burnam hopes that people’s expectations of Armendariz will be tempered by the realization that he will have to learn the system before he can make a difference. “I wouldn’t expect to see much of him the first few months, because it’s a big bureaucracy. It is a big agency that he has to learn,” he said.

Still, Texas environmentalists can’t help getting their hopes up. Their wish list reads like a letter to Santa. Hadden, like many of her colleagues, believes that Armendariz is capable of delivering on even the loftiest expectations.

“I’m hopeful in terms of air quality, in terms of toxins, that we might look at the mercury picture in Texas, especially coal-burning power plants,” she said. “Many of those permits have not been done properly. The law has not been followed, and we would like to take up those cases again.

“We hope that he will also pay attention to the radioactive waste dumping in Texas and also weigh in, as he’s able, on the various forms of energy that are being promoted. We’re worried about nuclear plants. They come with extreme environmental impact.”

But first, she said, “We’ve got to get compliant with federal law. We need to get our state implementation plan for air in place and get those goals met. Most of our major cities have been failing to meet air quality goals for some time. As a result we have children suffering from asthma and elderly people suffering from heart attacks and lung problems that send them to the hospital.”

Carman voiced a sentiment probably shared by many of those concerned about Texas’ environment.

“This is amazing that this is all happening, but I’m glad that it is,” he said. “This is a mess that needs to be cleaned up.”