In my 21 years in FWISD I have not worked with a finer AP than Joe Palazzolo. Mr. P is hard-working, on the job every hour of every day. He is proactive, consistent, fair, and has a wonderful sense of humor. … Our 9th grade teachers have appreciated being able to count on Mr. P’s support. This past year he was given many unpleasant tasks because [Principal Neta] Alexander knew that she could count on him to get the hard jobs done when others had dropped the ball. When one is given the dirty work, one often runs into resistance. … Please reconsider leaving Mr. P at Heights. —Linda Bobo, English Department chair and ninth-grade team leader

My Name is Mike Mihalik and I am the FWISD Chair for Teaching Excellence in Secondary Math this year. … Are you aware of how integral Mr. Palazzolo is to the success of our Heights teams? [He is] the only administrator that all of the students recognized because he was always in the halls. Trust me, Mr. Palazzolo was the only administrator that disruptive students respected. … If you ask the students … that got bullied or the students that made mistakes but got turned back around again, Mr. Palazzolo was a hero. … This is an administrator that is truly making gains in closing the achievement gap at our school. … If outstanding work like his is not recognized in this district, then there is a frightening gap between what we say and what we really mean. … If you don’t listen to the faculty and staff that are … putting their hearts and lives into turning this district around, to whom are you listening?

My Name is Mike Mihalik and I am the FWISD Chair for Teaching Excellence in Secondary Math this year. … Are you aware of how integral Mr. Palazzolo is to the success of our Heights teams? [He is] the only administrator that all of the students recognized because he was always in the halls. Trust me, Mr. Palazzolo was the only administrator that disruptive students respected. … If you ask the students … that got bullied or the students that made mistakes but got turned back around again, Mr. Palazzolo was a hero. … This is an administrator that is truly making gains in closing the achievement gap at our school. … If outstanding work like his is not recognized in this district, then there is a frightening gap between what we say and what we really mean. … If you don’t listen to the faculty and staff that are … putting their hearts and lives into turning this district around, to whom are you listening?

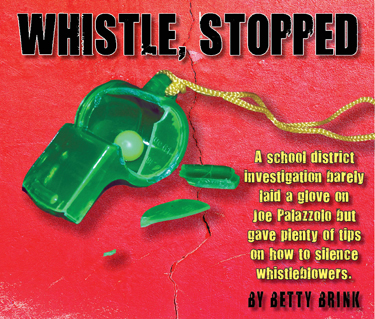

When the Fort Worth school board voted on Oct. 26 to fire Joe Palazzolo, they did so, presumably, on the basis of a 290-page investigative report that dug deep into the past and present of the former Arlington Heights High School assistant principal, the man who, not coincidentally, is at the eye of the hurricane of a scandal that in recent months has grown far beyond the bounds of that Westside campus.

The report included page after page of rumor and innuendo regarding Palazzolo. But no school trustee who read the 3-inch-thick report from front to back would have found either of the above comments, which are just a sample of more than 80 e-mails from Arlington Heights teachers that were sent in June to Superintendent Melody Johnson and two other administrators on Palazzolo’s behalf. Only one such favorable e-mail was included in the report.

Trustees would, however, have found an eight-page section called “Colleague Concerns … A Brief Study,” authored by Kerwin Cormier, another former Heights assistant principal who, the report suggests, was asked by the district’s investigator to spy on Palazzolo, including searching his office. Cormier accuses Palazzolo of everything from stealing “paperwork items” from her office to having had some role in the appearance of a bong on another administrator’s desk — but admits repeatedly that she has no proof. “I do not have eyewitnesses, but clues point to him,” she said at one point. “We were never able to get proof” she wrote another time.

The report doesn’t mention that Cormier herself was implicated in the attendance fraud that was a major part of the allegations Palazzolo documented at Arlington Heights after teachers and others brought the complaints to him. The district’s Office of Professional Standards, in a separate investigation, has confirmed the majority of the allegations reported by Palazzolo, including the attendance fraud, thefts, disparate treatment of minority students, sexual harassment, and failure to enforce truancy laws. Records show that Cormier, as head of the school’s attendance committee, was informed on at least two occasions that attendance records were being altered for chronically absent seniors who would not have been able to graduate otherwise. She was never charged, however, and after the scandal broke, she was moved to an administrative post at another school.

School board members would also have been able to read in the investigative report eight pages of e-mails about scheduling — essentially complaints that Palazzolo had inconvenienced some people. And they would have found, in this critical and official document, a set of unsigned sticky notes attached to e-mails from Palazzolo himself, in which the anonymous writer gives his or her interpretation of what Palazzolo is really saying, always with negative overtones.

The report includes the investigator’s charge that Palazzolo committed a firing offense by failing to disclose two decades-old misdemeanor charges in his past. Palazzolo freely admits both incidents — one involving being taken to court by his ex-wife over child support payments and the other that an employee of a security company he once ran was found to have an expired security officer’s license.

But what neither the report nor Palazzolo’s own file contains is any document that would show that, at the time Palazzolo filed his application to work for Fort Worth schools in 2005, the district’s policy even required misdemeanors to be listed. Despite requests by Palazzolo and others to the district, no copy of that year’s application policy has ever been produced. What has been produced — but which also was not included in the report — is a copy of Palazzolo’s signed contract, which only asks that the employee swear that he has never been arrested or convicted of a felony or any crime against children that would make him ineligible to work with students.

Nor does the investigative report mention a much more troubling fact about criminal records at the Fort Worth school district. According to records released recently, nine current employees of the district — eight teachers and a mechanic — were allowed to return to work after being convicted of at least one felony. The convictions on their records are no technicalities — they include injury to a child, various forms of aggravated assault, forcible rape, sexual harassment, sale of heroin, possession of cocaine, and even child molestation. In recommending that those employees be allowed to return to duty, the OPS investigator wrote that policy does not require the district to take action in such cases, but only says it could act.

Ironically, in each of those felony-related cases, the records show employees were called in and given a chance to explain or defend themselves. That courtesy, however, was not extended to Palazzolo. “I didn’t even know the charges that were leveled against me or who my accusers were until I was given the investigative report,” he said. The report was released to him the day before the board voted to fire him.

In fact, until Palazzolo became the bearer of bad news at Arlington Heights by reporting the teachers’ concerns, there was no charge of misconduct of any kind in his personnel file. Despite the fact that district policy requires that allegations against employees be made in a timely manner and that the accused person be informed, also in a timely manner, none of the things Palazzolo is charged with in the report were ever the subjects of written complaints in the past. What were in his file, until the Arlington Heights scandal arose, were only positive, not to say glowing, evaluations.

In short, said Larry Shaw, head of the county’s largest teachers’ group, “This is a classic whistleblower retaliation case.”

The investigative report is “a joke,” he said. “The only thing left to believe is that the Arlington Heights scandal has been such an embarrassment to Melody Johnson that she had to kill the messenger.”

When Palazzolo reported the longstanding problems, including potential state and federal crimes, that dozens of Heights teachers and coaches reported to him, he didn’t expect a reward. He did believe, however, that a grateful administration would immediately begin to “clean the mess up,” he said. Instead, within weeks, a series of retaliatory measures were launched against him: He was demoted and given a pay cut, moved twice to different schools, and then put on administrative leave. And finally he was fired, based on Johnson’s recommendation and the findings of the investigative report.

Much of the investigation of Palazzolo was done by J. Adam Binnix, a former University of Texas at Dallas police officer who was hired by the Fort Worth district’s OPS office earlier this year.

For something prepared by a law enforcement officer, the document has a lot of what might be termed evidentiary problems. For instance, the report includes Binnix’s request to an Oklahoma sheriff for information on an alleged arrest of Palazzolo for “illegal entry” in 1988. In the letter, Binnix wrote — in all-capital, boldface letters — that the sheriff should not disclose the existence of the request because “disclosure … could impede the current investigation and thereby interfere with the enforcement of the law.” There was no explanation of what law was being enforced since Palazzolo was never accused by the district of committing a crime.

More importantly, no documents were included to show that the sheriff ever responded to Binnix’s request. And while Oklahoma is the state where Palazzolo lived when the two misdemeanor charges were alleged to have been filed against him, neither, he said, had anything to do with illegal entry.

The net result: an entry in the report that would raise a question of illegal activity, but with no indication that there was ever even an official allegation of that, much less a charge filed or a conviction obtained. And with no acknowledgment in the report that no substantiation was found.

Reached by phone, Binnix angrily asked, “How in the hell did you get my number?” and then declined to comment.

Reached by phone, Binnix angrily asked, “How in the hell did you get my number?” and then declined to comment.

Indeed, much of the hefty tome is a recitation of hearsay. Several allegations come with the caveat, “I have no proof of this, but …,” after which the writer goes on to report an allegation with no substantiation provided either by the person making the allegation, by Binnix or by Michael Menchaca, the head of OPS who oversaw the investigation.

The report includes e-mails between Palazzolo and other administrators and teachers regarding various events that occurred during the year, ranging from the very serious (theft of computers, a racial fight) to the mundane — but involving no allegation against Palazzolo.

Other portions are a recitation of accusations against Palazzolo that, even if true, included nothing more than low-level criticism of how he did his job. In a series of e-mails between Palazzolo and counselor Danyatta Harrell, for instance, the two discuss a freshman student with dyslexia whose diagnoses had been missed by the counselor. Put in a class without special accommodation, the student lost his first-semester credits.

Palazzolo was trying to facilitate a meeting between the staff and family in order “to help this student recapture what was lost.” In one message, describing a meeting with the family, he wrote that the student was crying. One of the unsigned sticky notes included in the report read, “Counselor said parent was pleasant and fine, Joe said she was crying — JP trying to create unneeded drama.” In fact, in the e-mail, Palazzolo had said only that the student was crying, not the mother. The question of why the incident was even included in such a report was

left unanswered.

After the investigation of Palazzolo began, Harrell filed a complaint against him with OPS for allegedly causing her professional harm by including her missed diagnosis in the boy’s file. Interestingly, in an earlier e-mail, she had thanked Palazzolo for working with her on the case.

I have been a special education teacher/department chairman at Arlington Heights for 31 years. … I would like to lend my support to keep Mr. Palazzolo at Heights. I have found him to be an exceptionally efficient and caring assistant principal. … I have worked with him on behalf of several students and feel that he does everything he can to help the students. If you wanted to find him during lunch he was always with the students. … we need his zeal for doing his job in order to continue to help the students. — Jane Routen

As in many whistleblower cases, Palazzolo was an employee who had proven his worth. His evaluations were filled with “exceeds expectations.” After only a year at Heights, he had been chosen by Alexander to be the go-to guy on campus for employees who wanted to report any allegations of what they suspected might be fraud, student abuse, sexual misconduct or harassment, or any other violations of school policy or state or federal law. It was a new program under the district’s office of diversity training, set up by Johnson and headed by Sharon Herrera, to provide a safe path for employees to report illegal or unethical practices, with Johnson’s assurance that there would be no retaliation against anyone reporting such wrongdoings. The purpose, according to district documents, was to identify and correct problems early before they rose to the level of a lawsuit.

As in many whistleblower cases, Palazzolo was an employee who had proven his worth. His evaluations were filled with “exceeds expectations.” After only a year at Heights, he had been chosen by Alexander to be the go-to guy on campus for employees who wanted to report any allegations of what they suspected might be fraud, student abuse, sexual misconduct or harassment, or any other violations of school policy or state or federal law. It was a new program under the district’s office of diversity training, set up by Johnson and headed by Sharon Herrera, to provide a safe path for employees to report illegal or unethical practices, with Johnson’s assurance that there would be no retaliation against anyone reporting such wrongdoings. The purpose, according to district documents, was to identify and correct problems early before they rose to the level of a lawsuit.

Palazzolo, who was head of the ninth-grade students and their teachers, took the job seriously, he said, a fact that doesn’t surprise Joel Riling, the senior naval science instructor at the school last year. He recently quit and moved

to Michigan.

Riling and others suggested that some of the sour-grapes complaints included in Binnix’s report come from those who didn’t like Palazzolo’s military style or his penchant for strict enforcement — including of the school’s much-ignored dress code. Palazzolo, a retired army captain and a 12-year veteran teacher, was known to be a straight arrow, Riling said.

“He was the best administrator the school ever had, the only one who really paid attention and tried to enforce discipline, and there was a great lack of discipline there,” said Riling, himself a retired naval officer. “There was a dress code, but it wasn’t enforced except in our program. … The only time the principal was interested in enforcing it or any discipline was when there were guests coming from the administration.

“The school was a behavioral disaster,” he said.

One of the allegations belatedly lodged against Palazzolo was that he discriminated against black and brown kids and favored whites. It’s a charge that has startled supporters like Riling.

“Any allegation that he [discriminated] against minorities is nonsense,” Riling said. “Whenever a minority student needed help, he was always there. … I can’t imagine where that came from. … He was definitely an enforcer, but he treated all of the kids fairly and equally.”

The evidence submitted in the report to back up the racial favoritism allegation is that the assistant principal referred a greater number of minority kids to disciplinary proceedings than other assistant principals did.

If that’s true, Palazzolo said, “it’s because I referred a greater number of all races for disciplinary proceedings, because I had a greater number of discipline cases.” And in part, his greater number of cases was due, he said, to the fact that he was over the freshman class, easily the largest and traditionally the most problem-prone class at the school.

The district submitted documents to investigators showing that for the 2009-2010 school year, disciplinary referrals were made at Heights for 59 black students, 25 Hispanics, and 22 whites — with Palazzolo responsible for the majority of the cases in all three ethnic groups. However, when the district compared Arlington Heights’ ethnic breakdowns to those of other high schools, Heights came out at the low end of the scale on referrals for black and brown kids and the high end for whites. For example, Eastern Hills referred 147 black students and 27 Hispanics to hearings that year compared to 13 whites; Southwest referred 82 minority students and only nine whites.

Mihalik, current holder of the district’s math teaching excellence chair, wrote in his e-mail supporting Palazzolo, “I work with the students and parents that the district needs to focus on (low income, minority, at risk) and I know what Mr. Palazzolo did for them on a daily basis.”

Complaints were filed against Palazzolo by a couple of parents whose kids were sent home from last year’s prom because they had been drinking. Again, it appears that the complaints were filed long past the deadline required by district policy and the state’s education code and only after Palazzolo helped uncover other scandals.

One of the girls was the student body president. Cormier and others said that Palazzolo bullied the kids that night, “put his hand on the girl’s shoulder” to push her back to her limousine, and failed to call parents to come get the kids suspected of being drunk.

“The charges are all just nonsense,” Palazzolo said. “I was one of five assistant principals there and several teachers. There were also police officers there. They did the tests for kids suspected of drinking, and I made sure the parents were called when the kids were turned away. And I never touched the girl.”

Many supporters echoed Linda Bobo’s statement that Alexander used Palazzolo “to get the hard jobs done when others had dropped the ball” and was less popular because of it. Nonetheless, the supportive e-mails still poured in after Palazzolo started taking flak from

Many supporters echoed Linda Bobo’s statement that Alexander used Palazzolo “to get the hard jobs done when others had dropped the ball” and was less popular because of it. Nonetheless, the supportive e-mails still poured in after Palazzolo started taking flak from

the administration.

“I’m not surprised that the district wasn’t forthcoming with [the board] about the supportive e-mails — it withholds information all the time — but I’m very disappointed,” said Northside trustee Carlos Vasquez, who voted against the firing along with board members Juan Rangel and Ann Sutherland. The e-mails “would not have made a difference in my vote. I never believed the district provided any solid evidence to justify Palazzolo’s firing,” he said. “But I [hope] the e-mails would have painted a clearer picture for those board members who voted to fire him.”

One of the more curious aspects of the report is the role played by Cormier, head of the Heights attendance committee. One of the most serious allegations raised by Palazzolo and validated by district officials concerned widespread attendance fraud. The allegations from teachers and others implicated Principal Neta Alexander, Assistant Principal Harold Nichols, and the girls’ athletic director, Isabelle Perry, all of whom resigned.

Although Cormier was never charged in the attendance scandal, her name popped up on a few documents, indicating that she was being made aware that records were being changed. Perry signed two altered attendance records in May with a note to “Kerwin” stating that she had cleared up eight absences for one student and 20 absences for another, both seniors who would not have graduated otherwise. On another attendance sheet for a senior with excessive absences, an unnamed teacher wrote: “Cormier — here is what this student has made up … 21 hours total. … Hope this fulfills the agreement!?! … Please advise if more info is needed.”

After the scandal broke, Cormier was transferred, — but not before she played a major role as an investigator for Menchaca, the head of OPS. E-mails included in the Palazzolo report show that she was gathering evidence for Menchaca by searching Palazzolo’s office and taking pictures of what she found as “evidence.”

One of the more serious incidents at the school last year was the theft of dozens of school computers in two separate break-ins, the first reported initially by janitors. E-mails between Palazzolo, the district’s security department, and Fort Worth police officers show that Palazzolo was working closely with both departments to trace and recover the equipment, which was eventually found.

One of the more serious incidents at the school last year was the theft of dozens of school computers in two separate break-ins, the first reported initially by janitors. E-mails between Palazzolo, the district’s security department, and Fort Worth police officers show that Palazzolo was working closely with both departments to trace and recover the equipment, which was eventually found.

However, in an e-mail to Menchaca on July 16, Cormier suggested that Palazzolo might have been involved in the second break-in because he was in the building at the time. She attached an e-mail from Perry to Alexander reporting that Perry had been informed that “Joe Palazzolo was in the building from 1 a.m. until 4 a.m.” and that he called in the robbery before the janitors did.

“When I went to look in Mr. P’s office I found some interesting items. Why would an AP need the following items: a toolkit containing pliers, hammer, screwdrivers, and box cutter, an electric screwdriver, and a brand new crowbar?” Cormier continued. She indicated that she had done a thorough search of her fellow administrator’s office, telling Menchaca that she found the items in “the restroom closet area, in his desk drawer, against his desk by the wall.”

“I have pictures of all of the items I will be sending as soon as I can get them uploaded from my phone,” Cormier wrote. “Just let me know when you’re ready for me to quit sending evidence. There is tons more and statements I could write about other incidents … the list goes on.”

Calls and e-mails to Cormier and Menchaca seeking comments for this story were not returned.

Palazzolo said he was stunned when he read that e-mail. “I had no idea she was spying on me or that the district was using her to do this,” he said. “She must have had a set of master keys — my door was locked.” He said her suspicions about the tools could have been cleared up if she had just asked him or Alexander. “We had a head custodian who refused to do anything like small or even major repairs. I was fixing things around the school on my own, with my own tools from home. Neta saw me one day and told me not to use my own tools but to go buy what I needed at Lowe’s where we had an open charge account. I did. The answer is just that simple. … But no one asked me to explain it.”

Alexander could not be reached for comment, but several teachers, who asked for anonymity, confirmed the fact that Palazzolo was the one they called when something broke in their classroom or they needed a “handyman.”

Palazzolo said he was indeed in the building the night the break-in was discovered, doing paperwork for some upcoming hearings for at-risk students, but that the janitors discovered the break-in and were the first to report it. A police report confirms that.

When Palazzolo read Cormier’s allegation that he had stolen “paperwork items” relating to attendance from Cormier’s desk, he said he had no key to her office, which she kept locked, and that, “I never had attendance documents in my possession.”

Mr. Palazzolo has handled himself both ethically and professionally during some very challenging times at Arlington Heights and has made some very difficult decisions for the benefit of the staff as well as the students we serve. … He has shown outstanding leadership throughout his tenure and implemented great programs that have benefited our school. As our Diversity leader he has promoted a work environment free of harassment and abuse. … To punish those that come forward in stopping harassment, abuse, and illegal conduct would be a disgrace to our reputation to those in the community we serve — Chad Whitt, special education teacher and head coach, boys soccer.

While the investigation of Palazzolo was going forward, the district was also proceeding to check out the allegations that Palazzolo had compiled. Three top-level administrators and an athletic director were found to have knowingly engaged in activities that violated district policy, the state penal code, and federal statutes. Johnson allowed them all to retire or resign “in lieu of further action.” Two of the administrators will continue to draw their full annual salaries for the balance of their contracts, which run through August 2011, according to district spokesperson Barbara Griffith. Alexander makes $105,000 yearly and Boyd $130,000.

That decision has outraged Vasquez. “This is just crazy,” he said, “to reward the very people who have defrauded the district’s taxpayers and our children.”

After the board voted to fire him, Palazzolo was approached by two lawyers who work for the district, offering to rescind the firing and let him resign. But Palazzolo declined the offer because, he said, he has done nothing wrong. “I told them I would meet them in court,” he said.

“There is a culture of fear now in this district,” he said, “and the lengths to which the district went to retaliate against me are just sickening.”

Whitt and Shaw both echoed his concerns. Shaw, head of the United Educators Association, said the Johnson administration’s efforts to silence and then punish Palazzolo for reporting wrongdoing have not been lost on the teachers Shaw represents. “That was the purpose of this whole effort, to send a message to the employees in this district that they better not speak out or they will be next,” he said.

Whitt said that the many teachers who support Palazzolo at Heights have gotten the message as well. “We all fear for our jobs, because the administration knows who we are,” he said after the meeting at which Palazzolo was fired.

Palazzolo has appealed the board’s decision to the Texas Education Agency, a process that Shaw said should be “much fairer than the board hearing.” Palazzolo will be able to present evidence and call and cross-examine witnesses under oath.

His attorney, Jason Smith, has also filed a whistleblower lawsuit against the district in federal court. Palazzolo’s is the third whistleblower lawsuit to be filed against the district in the last year.

Shaw believes the district’s intent in retaliating against Palazzolo goes beyond just trying to silence other potential whistleblowers. He thinks officials in Johnson’s administration also are trying to “turn the attention to the whistleblower and away from the illegal activities he reported.”

Since the scandal broke, Shaw, Palazzolo, and Whitt have all said that teachers from other schools have told them that the problems at Heights are not unique, but widespread throughout the district. An employee on Johnson’s staff, who asked for anonymity, said that attendance fraud is occurring in a large number of high schools because there is so much pressure on principals to keep their completion rates high and their drop-out rates low so that their schools will not drop into the “academically unacceptable” rating.

The district is under investigation now by the Tarrant County District Attorney’s office for the possible theft of funds from the Arlington Heights booster club; the prosecutor in charge of the investigation said that if other charges of fraud come up, they could be added to the investigation. The Rev. Kyev Tatum, head of the local Southern Christian Leadership Conference chapter, has filed three complaints with the U.S. Department of Education based on charges that the civil rights of students and teachers have been violated at Heights.

“Mr. Palazzolo does not discriminate against minority children at Heights,” he said. “The problems there started long before he arrived on the scene. … He tried to correct the problems and got fired for it.”