About 470 years ago, famed Spanish explorer Francisco Vazquez de Coronado and his men got lost in the Texas panhandle. They floundered there for three weeks.

They were confounded by the endless plains. They were disoriented by what seemed to them a landmark-less sea of grass.

Recently, venturing west on a Texas county road toward Palo Duro Canyon, I crossed what used to be part of those amazing plains. Instead of indigenous grasslands, most of the area is now farmland.

Recently, venturing west on a Texas county road toward Palo Duro Canyon, I crossed what used to be part of those amazing plains. Instead of indigenous grasslands, most of the area is now farmland.

The beginning and end of this quiet 30-mile stretch are dotted with occasional houses, metal churches, and closed-down firework stands. The middle features wide expanses of shorn cotton fields and ember-like splashes of maize crops, some fenced, some not. There are at least two ancient buffalo wallows along the way, if you know what you’re looking for, and now and again you’ll see a disenfranchised coyote sneak across the road in broad daylight, with more of his brethren dead on the side of the road.

Every once in a while, however, there’s a break in the crops and fences, and you find yourself quizzically gazing out across a vast grassland, just like Coronado did.

It’s frightening to consider how quickly and utterly we’ve filled these wild expanses. Not quite five centuries ago, no one would have imagined it possible. But in the blink of an eye, really, we’ve done it. And sometimes we have the nerve to call it progress.

Out at Palo Duro, folks are building subdivisions practically right up to the canyon edges. Wild, untamable places are turning out to be docile and wobbly in the path of human “civilization” and technology. The frontier that was first sliced up by fences is now scarred by highway asphalt, so we can reach those less-and-less-wild places faster. We can now visit most of Texas from the comfort of fully enclosed, air-conditioned, rolling bio-systems, with power windows and GPS on board.

There are still a few spots where we can get lost, but they’re shrinking as fast as our water supply. Stretches in the Big Bend region come to mind and the forests and thickets of the Piney Woods area. But I fear for them too.

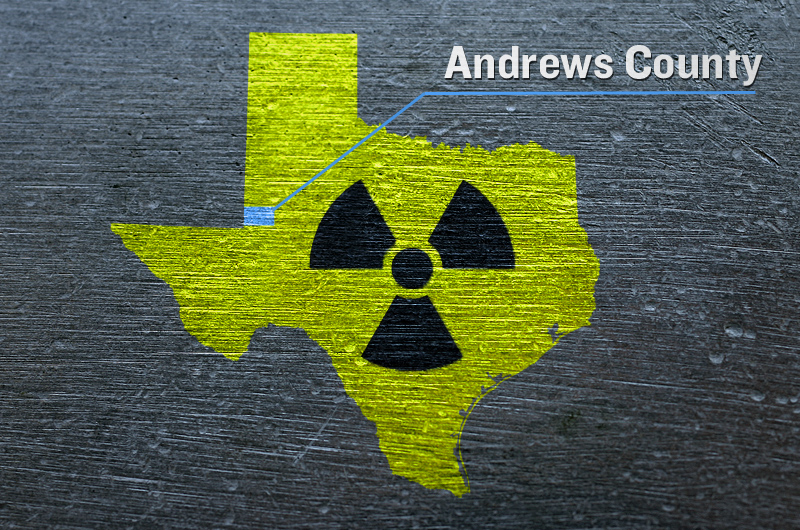

We like to talk about our pride in Texas, but some of the ways we’re exploiting our lands are nothing to be proud of. Andrews County out west of Big Spring now hosts a 1,338-acre dump for low-grade nuclear waste. Thirty-six other states are currently invited to deposit their nuclear trash here, and the dump sits in the precarious vicinity of our massive, precious Ogallala Aquifer.

Some folks talk about secession as if an independent Texas could be a first-world nation, up there with the developed countries. But our politicians have allowed a billionaire from Dallas to turn a part of the state into a third-world dumping ground. Three true-Texan scientists resigned from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality rather than sign off on the nuclear dump’s licensing, but their protests were like pebbles tossed into Lake Travis. They hardly made ripples, especially compared to the flood of lobbyist money that washed through Austin to seal the deal.

We’re not just losing Texas in far-off, empty places either. Right here in our own backyard, the natural gas cartel is using billions of gallons of our limited water supply to fracture the crust we live on and then injecting its toxic byproducts into disposal wells that are about as safe as the nuclear dump out past Big Spring.

There are now billboards all around town that herald the notion that the resultant natural gas harvest will last 100 years, but it’s a head-scratcher for any Texans who still have brains left to scratch.

One hundred years is nothing, except in terms of human encroachment.

Today, Coronado wouldn’t bother with Texas, and who could blame him? We’re selling off our state and our state of being to the highest bidder — although that too is perhaps a less-acknowledged but longtime tradition in this state. It is intensely sad.

E.R. Bills is a Fort Worth-based writer whose work has appeared in numerous publications.