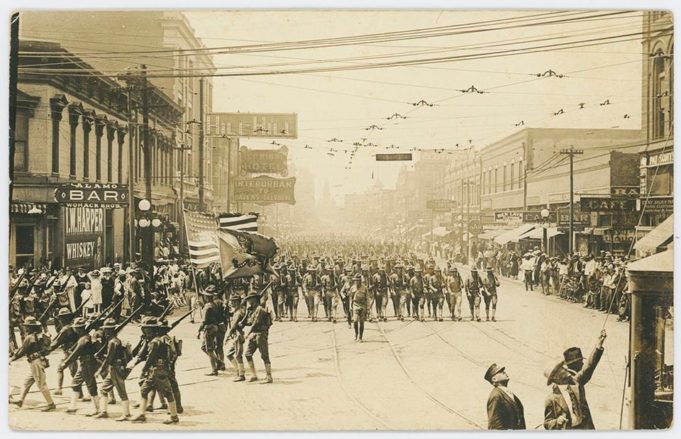

The Fort Worth of 1918 bore little resemblance to the cosmopolitan urban hub that it is today. Motor vehicles were a novelty, and the population was approaching the milestone mark of 100,000.

Fort Worthians of 1918 and 2020 began their respective years unaware of the scope of epidemics that would cause unprecedented upheaval and concerted efforts at every societal level to contain the deadly outbreaks.

The exact origins of the 1918 influenza pandemic are still debated. News reports at the time recounted an American plague that was less severe than the “Spanish influenza” that met U.S. troops in Europe that same year. The 1918 illness was known as the Spanish Flu as a result.

U.S. training camps at the time, including the army training base Camp Bowie, located in what is now Arlington Heights, were hit especially hard. The location was chosen because “the topography around the camp is the same type of topography found along much of the Western front,” geologist Ellis Shuler noted in 1917.

One newspaper at the time read, “The cold winter of 1917-18 had taken its toll on the troops at Camp Bowie. The 36th [Division, based at Camp Bowie] journeyed to France in July of 1918 and even MORE dreaded disease was yet to strike.”

Soldiers in Fort Worth were stationed in close quarters, often eight to a tent, as was the habit of the army at the time. By September, a flu pandemic was sweeping through North Texas.

Fort Worthian Russell Paddock enlisted around that time before reporting to nearby Camp Bowie, according to author Juliet George. Paddock contracted the deadly H1N1 virus and succumbed to the disease in a base hospital soon after.

His father, Ira Paddock, asked that the family physician be allowed to examine Russell before he died. Quarantine rules at the time did not allow for outside visits. Neither the father nor the doctor saw Russell before he died.

Around that time, schools, theaters, churches, and streetcars were closed in an attempt to slow the pandemic, according to Star-Telegram archives. Soldiers’ beds were spaced five feet apart, but the men of the 36th Division died by the dozen.

Fort Worthian Ray Copeland recalled the time when he, then 12, was asked to help carry bodies.

“I was a Boy Scout at the time,” he said. “And during the middle of the flu epidemic, we helped the medics in handling the bodies. It was awful.”

In total, an estimated 50 million died worldwide, including 675,000 Americans. The disease left almost as abruptly and mysteriously as it had swept in. By November 1918, when Germany formally surrendered and ended World War I, one American newspaper noted that “bells rang and whistles blew.”

Many people, the newspaper noted, “wept with joy, not only because victory had come but also because influenza was on its way out.”

This article would not have been possible without the generous help of staff from Historic Fort Worth Inc. and past reporting from the Star-Telegram. The two books sourced are Camp Bowie Fort Worth 1917-18: An Illustrated History of the 36th Division in the First World War and Images of America: Fort Worth’s Arlington Heights.