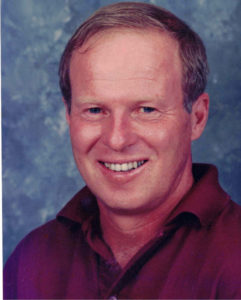

The man who served as Texas Wesleyan’s athletic director for many years died this month at the age of 86 after prolonged health issues.

The man who served as Texas Wesleyan’s athletic director for many years died this month at the age of 86 after prolonged health issues.

Family and friends gathered for a celebration of life Sunday at the Sid Richardson Center on campus. After having been hired at TWU (then known as TWC) in 1967, the deceased had put a great deal of his time, effort, and into the construction of that facility, which opened in 1970. The Rams’ women’s volleyball and men’s and women’s basketball teams play their home games there, as they did then. Yes, Wesleyan had women’s teams in 1970, two years prior to the passage of equality-mandating Title IX legislation.

In the run-up to the event, the leading scorer on that ’70-’71 squad emailed the former AD’s son.

“I was one of the few who started asking (sometimes begging) every professor in the physical education department, and even Catherine Wakefield, who was Dean of Women at the time, to be our coach. I can’t remember when or how your dad told me that he was going to coach the women’s volleyball and basketball teams. We were just a group of athletes who loved the sports and weren’t ready to give up on competing,” wrote Susan Watson.

“As I have thought back on the beginning of our campaign, and after coaching for twenty years, I realized how unselfish your dad was. He was already head of the physical education department, athletic director, teaching professor, and also the coach of the men’s and women’s tennis. If that was not enough to shoulder, he and Fran (his wife) had two young kids to raise,” she continued. “I know it must have been a difficult task to work with little or no funding for our program and we were NOT very good! We didn’t know that we weren’t very good, because your dad was always positive and complementary for our efforts. He was a very special and dedicated person who went way beyond the expectations of his job.”

Under his guidance, TWC became the first co-ed, four-year college in North Texas to establish a varsity women’s athletic program. As Watson noted, he served as a professor as well and viewed the educational effects of sport for the student-athlete as the number one priority in any athletic program. He saw no reason why female students shouldn’t receive those benefits.

Those who attended the celebration found out the man many called “Doc” received his undergraduate degree from Arizona State, where he played baseball and basketball. He earned his PhD from Ohio State. He won Texoma Conference titles as a coach, earned plenty of trophies playing tennis himself, and even scored four points in a March Madness basketball game as an undergrad. But Doc’s family and friends didn’t spend a ton of time talking about his exploits on the court or field. They spent more time on the values that influenced how he ran his teams and his departments.

In February of 1964, he wrote a letter to the editor of Ohio State’s campus newspaper. It rebutted a previous editorial encouraging spectators to boo the men’s basketball team’s archrival (which they apparently did). He found it unacceptable to jeer Michigan All-American Cazzie Russell’s “skill, finesse, and gentlemanliness.” He went on to write, “the appreciation of another’s value is not the degradation of your own . . . if sport can teach no other lesson, this would be the greatest rationale for its existence.”

Playing sports the right way meant everything for him. And sportsmanship was bigger than sports.

Former Texas Wesleyan baseball player Jeff Herr remembered when the athletic director joined his head coach, Brad Bass, to explain the concept of an honor call.

“If a play, a call, a ruling was made inaccurately—and went in your team’s favor (and you knew it), it was to be on your honor to make it known to the umpire and, subsequently, have that call reversed. If you ‘made’ a diving catch on a low liner to center and only you knew the ball was trapped on a short hop, you needed to be honorable. You needed to come clean. You needed to alert the umpire of what really happened.”

Herr noted that at the time, the concept didn’t resonate with a group of highly competitive young ballplayers. But as he progressed through life, earning his own doctorate and becoming an educator himself, Herr realized the bigger-picture implications of what he’d heard that day at Ab Adams Baseball Park.

“Doc’s advocacy for instituting honor in a dishonorable time was bigger than sports. Bigger than the bravado instilled and fostered in 18-22 year-old ballplayers. Heck, it was even bigger than baseball itself. Doc’s honorable idea was about human progress.”

Former Ram tennis player Norm Smith spoke at the ceremony about the influence his former coach had that extended on the court in terms of “competing fairly” and beyond it into life.

“We now realize the lasting impression that Doc made on our lives,” Smith said. He teared up as he said it.

I felt that effect, too, in every area of my life. Former Wesleyan AD Ed Olson was my father.

As my amazing sister Missi and I spoke Sunday, we tried to give the audience an idea of what our dad was all about. He was a superb athlete, but what made him truly special went beyond what he could do with arms and legs, though he was both strong and speedy. What distinguished Pops was how he thought about sport beyond just when to play a timely drop shot or hit behind the runner.

We showed a video with shots of the National Youth Sports Program. During several summers in the 1970s, TWC opened its athletic facilities to neighborhood kids who received instruction in activities like basketball, tennis, volleyball, swimming, and tumbling. I got to join in, too. After the ceremony, someone described me as a “beam of light” in the video because of the way my pale white skin contrasted with that of the African Americans with whom I played the sports we all enjoyed. I loved playing the games that summer, but the lessons I learned about humanity mattered a lot more in the long run than any drive to the basket or bounce on the trampoline.

Like all the best educators, my father didn’t just teach you what to think. He taught you how to think for yourself. That’s something he gave to my family that we’re happy to share with lots and lots of people.

A video recording of Edward Olson’s Celebration of Life can be viewed here. To donate to Texas Wesleyan’s Catherine Wakefield Scholarship Fund in Ed Olson’s memory, visit txwes.edu/makeagift.