In 1975, at a Greek restaurant in the provincial English countryside, Bob Pridden held a loaded pistol to the head of Lynyrd Skynyrd frontman Ronnie Van Zant, who appeared to be heroically chugging a bottle of whiskey. Pridden, the longtime soundman for The Who, wore a grin that betrayed the gravity of the situation, as a cigarette dangled from his bottom lip. There was no animosity between the two bands – they were just partying with a reckless lust for sensation.

Photographer Kate Simon, who was traveling with Skynyrd on the iconic Southern rock band’s U.K. tour, had snapped the photo of the scene. She was, as she always seemed to be, in the perfect place at an amazing moment – a theme that would repeat an incredible amount of times throughout her four-decade career.

“That picture is the essence of sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll,” she said during a phone interview from Manhattan, where she lives and works.

“Lynyrd Skynyrd, UK, 1975” is one of 136 other photos that will hang at Fort Works Art from May 10 to August 31.

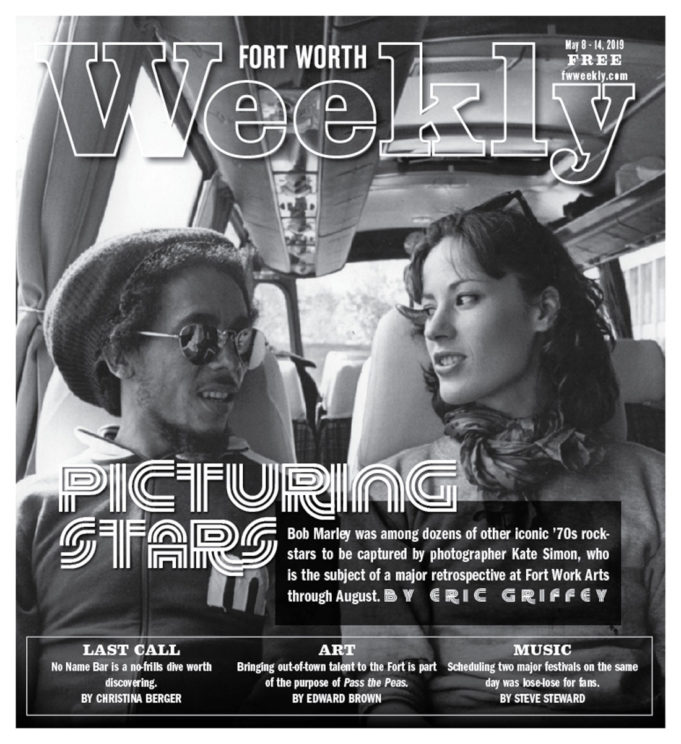

For Simon, perhaps best known for her iconic photos of Bob Marley before and during his meteoric rise to international stardom, Kate Simon: Chaos and Cosmos is the most comprehensive show of her work to date, featuring images from 1973 to as recent as 2011.

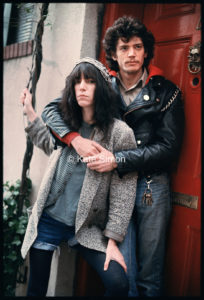

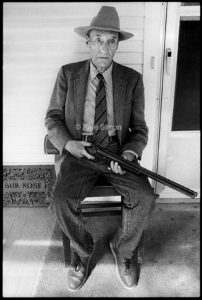

On display are Simon’s notable cultural friends and acquaintances, including towering figures like David Bowie, William S. Burroughs, The Clash (for whom she shot the cover to their eponymous debut album), Deborah Harry, Mick Jagger, Madonna, Robert Mapplethorpe, Lou Reed, Patti Smith, and dozens more. The collection also includes rare shots of important LGBTQ subjects such as Amanda Lear, India Menuez, and Terri Toye.

“I am fascinated by people who live the artist life, for lack of a better term,” she said. “That takes such a commitment.”

Simon’s work appears in the permanent collections of The Museum of Modern Art, the National Portrait Gallery/Smithsonian Institution, and the Andy Warhol Museum and has been published in countless publications.

Mostly black and white, the framed photos at Fort Works are at once elegant, shocking, and beautiful –– one of the biggest, clearest, and best-lit mirrors of our cultural zeitgeist. More than art, they’re historical documents –– portraits of a time when art, music, and culture intersected and transformed into something equal parts decadent and intimate. From behind a lens, Simon shows us a glimpse into the worlds of some of the most influential figures of their time.

“I usually just photographed what was right in front of me,” Simon said. “I photographed Joe Strummer and The Clash, but they were my best friends. I photographed William S. Burroughs, but he was very close with my best friend. I really didn’t go out of my circle of friends.

“I worked with [editor] Glenn O’Brien for Andy Warhol’s Interview Magazine, and Andy was just there,” she continued.

“Bob Marley I photographed because I was working in London before he really broke, and I saw him play at the Lyceum Theatre, where the live record was recorded, and he was so heart-stoppingly brilliant,” she said. “That all kind of came organically.”

Simon began her life-long passion in her hometown of Poughkeepsie, New York, at the age of 7, when her father, a doctor and avid amateur photographer, encouraged the pursuit by giving her a Polaroid camera.

“I felt as a young girl, when he would take my photograph … it was an act of love and respect,” she said. “That’s when the seed was planted.”

After college, Simon moved to London for a regular paying gig shooting for weekly rock publications. It was in the service of those magazines that she gained access to and developed close friendships with people who are now considered rock royalty.

“I photographed James Brown, The Who,” she said. “I was shooting someone famous offstage during the day and some brilliant act at night. I was touring with these people like Lynyrd Skynyrd, The Who, Led Zeppelin, and I would photograph them in rehearsal and offstage. I remember I had to go Rod Stewart’s house in Windsor once every month to photograph him.

“I really liked shooting Led Zeppelin offstage,” she added. “I liked going to Jimmy Page’s house. It was surrounded by a moat, and it had black swans in it.”

After seeing Marley at the Lyceum, Simon spent the next five years continually visiting Jamaica at the behest of various outlets and record labels. She worked all over Europe for a time, until she wound up back in New York in 1977. Everywhere she lived, Simon found herself at the nexus of whatever was cool and culturally important. Her work evolved as she explored more posed portraiture, though she still found herself backstage at the biggest concerts and edgiest punk venues.

“I try to go for something that has some emotion to it,” she said. “You just kind of think how someone appeals to you, and when you’re doing a photo session, you get into a flow with someone. I really try to take away something that is always physically flattering but also something that reveals a little about their intelligence.”

For Chaos and Cosmos, Simon was lured to Fort Worth by longtime friend Eddie Vanston, a local developer, co-owner of Shipping & Receiving Bar, and also a New York native. The two met through a mutual friend and recently reconnected while Vanston was visiting the Big Apple.

“I’ve always adored him,” she said. “Some people you just really don’t forget. He said, ‘I want to get you a show down in Fort Worth.’ He’s the one who put it together. He’s friends with Lauren Childs, and we’ve worked on this show for at least a year.”

Despite her many accomplishments and accolades, Simon said she doesn’t view herself as an icon, though she is to the point where she’s beginning to look back.

“I have to tell you, when they finally told me the first piece was admitted to the Smithsonian, I was driving upstate, and I pulled over to the side of the road and started to cry,” she said.

“I am grateful that I have work in big collections like that,” she continued, “but I don’t in any way think that anyone knows who I am at all. What I’ve been trying to do is realize that I’ve reached my potential.”