The fighter on his back is kind of like the scrappy wolverine, which at 40 pounds or so uses its leverage and claws and teeth to disembowel cougars and wolves, animals three times its size. The wolverine is a scavenger, naturally combative, beating other predators off carcasses or off its own belly. The wolverine knows that there are times it’s best to be on its back, other times to drop out of trees and pounce on a prey.

The fighter on his back is kind of like the scrappy wolverine, which at 40 pounds or so uses its leverage and claws and teeth to disembowel cougars and wolves, animals three times its size. The wolverine is a scavenger, naturally combative, beating other predators off carcasses or off its own belly. The wolverine knows that there are times it’s best to be on its back, other times to drop out of trees and pounce on a prey.

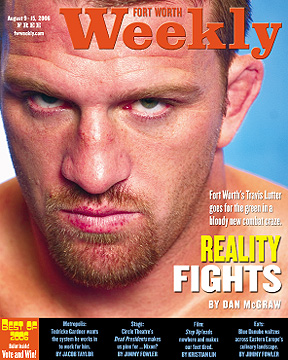

Travis Lutter is no wolverine; he does not snarl or sneer or show any real emotion while grappling. Like most of those who practice the martial arts, Lutter shows very little facial expression in combat. There’s also no yelling — something hard to do anyway when your neck is in a vise. Instead, the dominant sound is that of bare feet squeaking as they push up from the mat. In many fighting sports like boxing or even pro wrestling, the trash talking and testosterone-filled “my opponent is a wuss” attitude pervade the game, even in practice sparring. In Brazilian jiu jitsu, dominance is achieved by a calculating mind, a focused stare, and respect for one’s opponent. The fight is very much within the mind, not just in the muscles and sweat.

At this training session, Lutter — wide-shouldered but not overly pumped up like so many bodybuilders — is able to move through his opponent, using his legs, arms, and digits to reverse the situation. Within a few minutes he has managed to get behind his opponent, exerting a chokehold that makes the other fighter give up.

Here at the gym Lutter runs in east Fort Worth, 20 students are paired up, practicing these “in the guard” moves for an hour. In jiu jitsu, knowing how to grapple on the mat is as important as knowing how to throw a left hook in boxing. This style of fighting used to be practiced mostly in Europe and Asia. The combat sport of choice in America has always been conventional boxing, guys with big gloves who stand toe-to-toe and wallop each other. Do that enough, and one boxer eventually kisses the canvas.

But the fastest-growing combat sport here these days is called “mixed martial arts” or “ultimate fighting.” The fighters use skills from many disciplines — kick-boxing, karate, jiu jitsu, wrestling, and boxing — and they use them inside an eight-sided, chain-link-fenced ring called “the Octagon.”

Critics have been calling the sport “human cockfighting” and nothing more than barroom brawls for which disturbed fans shell out $39.95 for pay-per-views. Fox News’ Bill O’Reilly jabbed at an ultimate fighter and a promoter on a recent show, asking them “What are we, ancient Rome here? Is it going to be like lions in the ring next?” And Larry Bisig, a member of the Kentucky Sports Authority, told the Associated Press last week that he wants the state to outlaw it. “It defies logic that a cock rooster has more protection in the state of Kentucky than does a human being,” Bisig said. “This is not boxing. Ultimate fighting makes boxing look like a slumber-party pillow fight.”

Critics have been calling the sport “human cockfighting” and nothing more than barroom brawls for which disturbed fans shell out $39.95 for pay-per-views. Fox News’ Bill O’Reilly jabbed at an ultimate fighter and a promoter on a recent show, asking them “What are we, ancient Rome here? Is it going to be like lions in the ring next?” And Larry Bisig, a member of the Kentucky Sports Authority, told the Associated Press last week that he wants the state to outlaw it. “It defies logic that a cock rooster has more protection in the state of Kentucky than does a human being,” Bisig said. “This is not boxing. Ultimate fighting makes boxing look like a slumber-party pillow fight.”

And others insist that the videos popping up on the internet of teen-agers engaging in extremely violent fighting — including one tape sold earlier this summer of a kid in Arlington getting his head smashed into a street curb — are a direct result of kids wanting to emulate these “ultimate fighters.”

Recent studies suggest that ultimate fighters, indeed, sustain injuries more frequently than conventional boxers, but that the potential for serious head injury may be less — although the figures for both disciplines horrify those who don’t enjoy watching people beat the crap out of one another as a living or a sport.

There’s also another statistic in which ultimate fighters, despite their recent rise to pay-per-view prominence, differ even more dramatically from boxers than in the amount of blood shed: the amount of money shared. Getting their share of the millions being made, instead of pennies, could be the ultimate fighters’ toughest challenge of all — that and avoiding serious head injuries long enough to get famous.

Lutter, 33, has cauliflower ears from training and fighting, but he first got them when he wrestled in high school and college. He has had 12 “ultimate fights,” and the only injuries he sustained were a couple of small facial cuts. He doesn’t do this style of fighting because he gets off on kicking guys in the face and throwing opponents around in an octagonal cage.

“I liked wrestling, and I liked competition,” Lutter said, sitting on a bright blue mat in his gym. “I watched the UFC [Ultimate Fighting Championships] on tv and figured I could do that. I saw guys winning who I knew I could beat. So I studied jiu jitsu and other martial arts, learned boxing, and the fighting just evolved. It wasn’t some thing where I think my entire life and character is defined by beating some guy up in the ring. I just figured it was something I could be good at.”

Over the next few months, Lutter will be on the main stage for ultimate fighting. He was chosen for Spike TV’s The Ultimate Fighter reality show, in which 16 fighters shared a house for six weeks where they argued, trained, and fought each other in the ring. The series premieres Aug. 17, and the live series finale in October will have all 16 fighting on a UFC card. If ratings go as they have in the past, about three million viewers will watch, making it the highest-rated cable tv show of the year.

Lutter won’t say how he did in the fights (the series was filmed in May at a house in Las Vegas, and his contract says he can’t reveal the outcome). But he knows he could be on the verge of making a name for himself in this new and controversial sport. He is working on getting an agent for the first time and wants to line up sponsorships. He is opening a second gym on West Vickery Boulevard near the Railhead Smokehouse next month.

Lutter won’t be making a lot from the Spike TV action. The fighters earn $1,000 a week for the six-week series and could get another $12,000 if they win all their fights. It’s not a lot of money for such a highly rated show, but it beats the $300 or $400 per fight that he used to make in the ring.

And the paltry financial return is becoming a point of angry contention for many of the ultimate fighters. The Las Vegas-based UFC controls most big fights in this country, and the money filtering down to those in The Octagon has been only a fraction of what even mediocre boxers make. No one knows if the huge growth of ultimate fighting is just a passing sports fad or whether this new sport is going to go the distance and knock out professional boxing.

And the paltry financial return is becoming a point of angry contention for many of the ultimate fighters. The Las Vegas-based UFC controls most big fights in this country, and the money filtering down to those in The Octagon has been only a fraction of what even mediocre boxers make. No one knows if the huge growth of ultimate fighting is just a passing sports fad or whether this new sport is going to go the distance and knock out professional boxing.

“The pay is what it is right now,” said Lutter, as he prepared for another workout. “I expect it will grow over time, and I want to be a part of that. But I’m not in this for the fame. I don’t really care much about that. Being famous without money is just a bad idea.”

For those on the far side of 40, mixed martial arts, or MMA, bouts must seem like a boxing version of the X Games for the younger crowd. The ring’s chain-link fence came about in the early years of the sport, to keep the “ultimate fighters” from getting thrown into the spectators in the first few rows. And the ring, contrary to the rumors, has no ceiling to it. The fighters wear 6-ounce gloves (compared to 8- to 10-ounce boxing gloves) with fingertips uncovered, allowing grasping of any head or appendage that gets within arm’s length.

The fighters move toward each other, standing upright like boxers, and punches get thrown in the same way. But MMA skills borrow from the other combat sports: Kicks are allowed, wrestling an opponent to the floor is used — sometimes by grabbing a guy and spiking him to the mat — and dominating the opponent the same way Greco-Roman wrestlers do in the Olympics.

The popularity of the sport is not up for debate. This spring, Spike TV ran its third Ultimate Fighter reality series, and the audience numbers were striking. The major fan base for ultimate fighting is — big surprise — 18- to 34-year-old men, and Spike TV drew 799,000 of those on April 27. On that same night, ESPN2 showed a major league baseball game, OLN aired a National Hockey League playoff match, and TNT broadcast two National Basketball Association playoff games. For those three cable channels the combined 18-34-year-old viewership was 725,000.

In late June, a NASCAR race shown on the FX network drew 1.4 million total viewers. That same night, Ultimate Fighter on Spike TV drew 2.8 million viewers.

Several big UFC fights in Vegas have sold out 10,000-seat arenas and drawn more than 600,000 pay-per-views at $39.95 a pop. Add up those numbers, and each fight can bring in more than $20 million in revenue. Dana White, president of UFC, says the popularity is a generational thing. “Boxing [is] these people’s fathers’ sport. Our fans grew up on playing Mortal Kombat video games.”

And indeed, it was computers — specifically the internet — plus high-powered marketing that took MMA from an almost- bankrupt fringe sport 10 years ago to being the sport of choice for the Maxim magazine crowd today.

MMA competitions were introduced in the United States in 1993, styled after the popular vale tudo (Portuguese for “anything goes”) matches in Brazil. The promoters figured fans would love to have an answer to the eternal sports bar debate: Would a boxer or a sumo wrestler or a karate guy win in a no-rules tournament? Who’s really the toughest?

But the “no holds barred” fights — with head-butting, kicks to the groin, stomping on the head, no weight classes, no time limits — drew critics like wolverines to a wounded caribou. U.S. Sen. John McCain of Arizona led the charge to ban the competitions from cable television, describing them as “human cockfighting.” McCain sent letters to all 50 governors asking them to ban it, and the cable networks caved to the political pressure.

By 2001, the UFC was bleeding on the mat. White and two Las Vegas casino operators led a bid to buy the company. White will not reveal the purchase price, but news reports suggest it was about $2 million.

White and his partners redefined the sport and made it less violent. Fighters had to go through rigorous pre-fight medical tests and were forbidden to head butt, stomp or knee an opponent on the ground, or strike the throat, spine, or back of the head. With those rules in place, Nevada and New Jersey agreed to sanction MMA fights. Eleven other states followed, including Texas.

Timing was everything. Boxing had fallen on hard times, with no real characters to grab fans’ attention and a perception that promoters were setting up fixed fights to keep the money flowing. “When we bought this company, we did not want to make mistakes that boxing had made,” White said. “We wanted the sport to be real — not like pro wrestling — and make the fighters the biggest part of the show. The biggest problem in boxing is that the two biggest guys in the sport are [promoters] Don King and Bob Arum.”

The mainstream media were ignoring this new version of boxing, but the internet kept it alive. Its young male fans posted info on championship bouts results, profiles of the fighters, and pay-per-view marketing on a host of web sites. “UFC stayed alive on the web,” White said.

In 2004, Spike TV was looking for ways to build a new network aimed at younger men. “We were looking at [different]combat sports,” said Brian Diamond, senior vice president of sports and specials for Spike TV. The UFC “had approached us a few times before that, but we weren’t sure how the sport would be received. But then the UFC came back to us with an idea for a reality show. It was about building characters, getting inside the mind of the fighters.

“The Ultimate Fighter has been great for our network, but also great for the UFC as well,” Diamond continued. “The comparison people make to pro wrestling is very wrong. There is no predetermined outcome with MMA; it is about as real as it gets. And this show is able to take you inside that fighting, focus on guys who live together for weeks at a time and then have to fight each other in the ring. The audience seems to like this because it is a mix of real sports with a reality show.”

“The Ultimate Fighter has been great for our network, but also great for the UFC as well,” Diamond continued. “The comparison people make to pro wrestling is very wrong. There is no predetermined outcome with MMA; it is about as real as it gets. And this show is able to take you inside that fighting, focus on guys who live together for weeks at a time and then have to fight each other in the ring. The audience seems to like this because it is a mix of real sports with a reality show.”

The fourth Ultimate Fighter series starts next week, with Travis Lutter and 15 others who have previously lost UFC fights, being billed as the “Comeback” series. Lutter, who had lost twice, initially did not want to participate. “I didn’t consider myself any kind of comeback fighter,” Lutter said. “The way this sport works right now, anyone who fights 10 fights will lose one. It’s not like boxing, where they can set up a fighter to go 40-0. There are just so many variables in ultimate fighting. One quick move can mean the end of the fight.

“But my friends and family convinced me to do this because of the exposure,” Lutter continued. “It was the worst six weeks of my life, though. We had no internet and no phones and no contact with the outside world. We rode vans to training every day. You would have a conversation with a guy, and then 10 minutes later you would have the same conversation again. A lot of it was stupid conversations. But maybe that’s what they wanted from us.”

No fighting was allowed in the house. In a pre-released DVD of the first episode, Lutter appears only briefly. The best part of the first episode is Chicago-based fighter Shonie Carter, who calls himself “Mr. International” and pukes in a bucket during a workout.

Fort Worth’s Ultimate Fighter hope grew up in the little South Dakota town of Gann Valley, population 50, and like the cliché of farm boys from small towns, he’s quiet and unassuming. It’s not a lack of confidence but just the part of his upbringing that holds talking about yourself as akin to bragging.

Lutter worked his family’s 1,500-acre farm with four brothers and sisters, growing corn and wheat and raising cattle. He traveled 30 miles to school each day, and his 1992 high school graduating class had 32 students. “It was good and bad,” he said. “You have a lot of freedom growing up in a small town, but there is not a lot to do. You know everyone, and everyone knows you.”

As a star high school wrestler, he earned a scholarship to Northern State University in Aberdeen, S.D. But in his freshman year, his scholarship was revoked because, Lutter said, he was “partying too much.” He stayed in college for a few years on and off, and filled his time with classes in martial arts and kick-boxing. By 1994, he began to hear about ultimate fighting and to study up on it. Lutter saw ultimate fighting as a form of the ancient Greek sport of pankration, which also combined grappling, striking, and submission holds. “When I wrestled in high school, I liked to do research and read about the sport,” Lutter said. “The ancient Greeks had a sport that used many skills, and for me, when I saw ultimate fighting, it seemed to be so similar.”

Quiet and intellectual, Lutter never plays the false humility game that so many athletes use as a crutch. Unlike many athletes in such an emotional sport, he is calm and collected outside the ring and calm and collected inside.

But he does have a very wry sense of humor. When this reporter commented that the “in the guard” moves might be the subject of a “Gay or Not Gay” bit on Sportsradio 1310 AM “The Ticket,” Lutter laughed. “Don’t go there with that,” he said with a smirk. “All of us wrestlers in high school had to put up with that, because people always pointed out we were behind each other with our arms around their waist.”

After a few years in South Dakota, Lutter realized that there was little training up north for MMA. A friend had moved to Dallas and was studying with Brazilian jiu jitsu black belt Carlos Machado, and the area was becoming a hotbed for ultimate fighting. After traveling to Texas several times a year to take the martial arts classes, he decided to move here in 1995.

After a few years in South Dakota, Lutter realized that there was little training up north for MMA. A friend had moved to Dallas and was studying with Brazilian jiu jitsu black belt Carlos Machado, and the area was becoming a hotbed for ultimate fighting. After traveling to Texas several times a year to take the martial arts classes, he decided to move here in 1995.

He fought in many lower-rung competitions starting in 1998, events called Power Ring Warriors and Abu Dhabi Combat Club and HookNShoot. But he also competed heavily in jiu jitsu, finishing third in the Pan American Games and winning the Texas State Championship in 2001. Along the way, he also opened his own jiu jitsu instruction gym, first in Haltom City and now in Fort Worth. He got married and divorced, and now has a 7-year-old son who lives with him.

The money in the smaller fights was rarely more than $1,000, more often just a few hundred dollars. “I didn’t fight for a few years, because of the money,” Lutter said. “Some promoters wanted to talk me into it, but it wasn’t worth it. … I’m not going to get hit in the head for a few hundred.” Instead, he achieved a black belt and worked at supporting his family by running the gym.

He has about a hundred full-time students in his Travis Lutter Brazilian Jiu-jitsu Academy, and that pays the bills. The gym is located off Brentwood Stair Road in east Fort Worth; the building includes an apartment where he lives with his son and his current girlfriend. While Lutter is talkative in his own way about fighting, he likes to keep his family out of the conversation.

In 2004, UFC tapped Lutter at the last minute for a fight; he scored a second round knockout over Marvin Eastman and made $4,000. But Lutter lost twice in 2005, once to a chokehold and once to a decision. His designation as a “comeback” fighter shows how much power the UFC has over the sport these days. The company will sign fighters to two-year contracts, but nothing is guaranteed. If the UFC wants a competitor for the lower part of a fight card, the fighter gets a “2 and 2” payday, meaning he receives $2,000 for showing up and another $2,000 if he wins. The smaller promoters offer much less. In May, for instance, Fort Worth-based International Freestyle Fighting (IFF) held an eight-fight event at the Will Rogers Center. Lutter, the headliner, made just $700.

The fighters are unhappy about this payday system now, but they are afraid to complain about it. In Lutter’s contract, UFC even controls his life’s story, meaning he’s not allowed to write an autobiography or work with a filmmaker to tell his story. The UFC controls the millions now, and they can dump anyone they want at any time. For any reason.

The fighters are unhappy about this payday system now, but they are afraid to complain about it. In Lutter’s contract, UFC even controls his life’s story, meaning he’s not allowed to write an autobiography or work with a filmmaker to tell his story. The UFC controls the millions now, and they can dump anyone they want at any time. For any reason.

The trick is for fighters to hang around long enough to make a name for themselves and thus gain some bargaining power. But that’s not easy in a sport this unpredictable and physically chancy.

Critics of ultimate fighting say that jumbling up all the fighting styles has created a sport that is going to get some fighter paralyzed or even killed. The promoters and fighters point out that no one has been severely injured or killed in the 12 years of its history and that this is just the latest version of a sport that has been popular with the public since ancient times.

The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine released a study on the injury rate of MMA fighting earlier this year, trying to gauge the health effects of “strikes from elite athletes, particularly professional boxers, [which] can generate a significant amount of force — equivalent to a padded wooden mallet with a mass of 6 kg. (13 lbs.) if swung at 20 mph.” It found that MMA fighters, on average, sustain more injuries — but possibly fewer serious head injuries than boxers.

Researchers studied the injuries sustained in 171 MMA matches, involving 220 fighters from 2001 to 2004, and compared them to boxing. The report noted an important difference between the two sports: MMA fighters are also allowed to “tap out,” meaning they can tap three times on the mat or on their opponent to end the fight if they feel they are losing or getting pummeled. In boxing, the fighter can quit from the corner after a round, but during a round, only the referee can stop it.

“This unique characteristic, combined with more options of attack when competing, is thought to help explain a knockout proportion in MMA competitions that is almost half (6.4 percent) of the reported 11.3 percent of professional boxing matches in Nevada,” the study said.

“With the growing concern over repetitive head injuries and the risk of dementia pugilistica among career boxers, decreasing the number of head blows a fighter receives during a match has been promoted as an important intervention,” the report said. “With MMA competitions, the opportunity to attack the extremities with arm bars and leg locks and the possibility of extended periods of grappling could serve to lessen the risk of traumatic brain injury.”

The researchers found that an average of 25 injuries per 100 fighters were sustained in boxing matches, compared to 28.6 per 100 for MMA. Researchers could not determine what the long-range expectation of head injuries might be for ultimate fighters.

“Mixed Martial Arts competitions have changed dramatically since the first Ultimate Fighting Championship in 1993,” the report concluded. “The overall injury rate in MMA competitions is now similar to other combat sports, including boxing. Knockout rates are lower in MMA competitions than in boxing. This suggests a reduced risk of [traumatic brain injury] in MMA competitions when compared to other events involving striking.”

Lutter said he has never felt in danger in MMA fights. “In boxing, you can get hit in the head 30 times per round,” Lutter said. “In ultimate fighting, getting hit 30 times in the head during an entire bout is a lot. Plus there is a lot of grappling on the mat and ways to be more defensive.

“It’s funny, because they have always marketed this sport as being more real, more violent,” he said. “The fans think they are watching gladiators. But the way this sport works, there is less violence than in boxing. And you can always tap out if you are getting beat really bad. In boxing, they usually only stop it when a guy is knocked out.”

Guy Mezger, 38, owns the Lion’s Den Gym in Dallas and did martial arts fighting for 17 years. He was a wrestler at Plano East High School and then at Texas Tech University. Like Lutter, Mezger merged kick- boxing and full-contact karate with his wrestling and fought in some of the early UFC matches (when there were no rules) in 1994 and 1995. Mezger also fought for a few years with PRIDE in Japan, one of the largest MMA promoters in the world.

“In those early days there were no rules, and guys like me were enthusiasts,” Mezger said. “The athletes were such a diverse group. Some were really good fighters, and others were just real delusional, thinking they had talent. I remember one kick-boxer knocked the teeth out of a sumo wrestler in the ring. If they had the no-rules fighting today, the athletes are all so good that someone would be killed.

“The problem now is that there are many talented fighters, but there is not really any world championship,” Mezger said. “Companies like UFC own the rights, and their fights are really a UFC championship. The business side is very much like pro wrestling in a way. The fighters are employed by the promoters, and they determine who fights and how it is marketed. It is very good for the growth of the company, but overall it is not that great for the fighters.” Eventually, he said, “someone will come along and figure out how to use a sanctioning body to create real-world championships among the fighters who have contracts with the UFC and those who don’t.”

When boxing was in its heyday, sanctioning bodies controlled where fighters were ranked and what match-ups would determine world champions. Part of the problem with boxing now is that it has degenerated into a multitude of alphabet belts —17 divisions and 68 champions at any given time — and promoters like Arum and King have too much control over who fights for all these world championships.

UFC’s White says the paydays for ultimate fighters are getting bigger and that any sanctioning bodies will ruin the sport. “We are sanctioned by the state athletic commissions, and as promoters, we build fights and build stars,” he said. If sport-wide sanctioning bodies are created, “I hope I’m not in it anymore.”

Tra Telligman of Bedford also fought in MMA fights from the beginning. He too sees the business model eventually following that of boxing. “Just like boxing, it all comes down to how many PPVs [pay-per-views] you sell,” said Telligman, who owns a construction business. Over time, he said, “the stars of the UFC will become more popular and have the power to negotiate. The UFC has made good decisions on keeping it real, but eventually you’ll have fighters making $10-20 million a fight and promoters getting their cut. All this will happen if the growth continues.”

Tra Telligman of Bedford also fought in MMA fights from the beginning. He too sees the business model eventually following that of boxing. “Just like boxing, it all comes down to how many PPVs [pay-per-views] you sell,” said Telligman, who owns a construction business. Over time, he said, “the stars of the UFC will become more popular and have the power to negotiate. The UFC has made good decisions on keeping it real, but eventually you’ll have fighters making $10-20 million a fight and promoters getting their cut. All this will happen if the growth continues.”

Already, big corporations are seeing the numbers and wanting in. The younger male demographic is key for a company like Anheuser-Busch, and it is why they do so much sports marketing.

Dean Bonham is president of The Bonham Group, a Denver-based sports marketing firm that is among the most influential in the country. Bonham said ultimate fighting has a chance to overtake boxing in the next decade, and the big corporations, which viewed MMA so negatively a few years ago, are taking note. With ultimate fighting, he said, beer companies and car companies have a very concentrated audience of young men to appeal to. The corporations “are watching this very closely right now.”

The major questions for such companies right now, Bonham said, is whether to give their advertising dollars to the sport in general or to the individual fighters. “The very nature of this type of fighting is that you won’t have champions who can last for years,” he said. “But if the number of fans continues to increase, the fighters will become the characters and personas that companies want to use in their marketing.”

The question is whether ultimate fighters can withstand the punishment to market themselves for a long time. Boxers have always faced this problem.

“I don’t ever think I’ll end up stupid after all this fighting,” Lutter said. “But [Mohammed] Ali would have told you the same thing. … Did getting hit in the head cause his Parkinson’s disease? No one knows that.”

So who are the fans of this sport? “I see it as a guilty pleasure, something my wife doesn’t get, but something I really have fun with,” said Glenn Terrell, a 40-year-old local chef. “I think it is the multi-discipline aspect of it that is appealing. It is a lot faster, and it appeals to my impatient side. I had to sit through those boxing matches with my father — six or seven or 10 rounds. This is just a lot more dynamic, and for whatever reason, I found it keeps me on the edge of my seat unlike any other sport.”

Bob Sturm, sports talk radio host on “The Ticket,” is one of the few members of local sports media on board with ultimate fighting. “I was a big boxing fan, and the problem with boxing has been well documented,” Sturm said. “Boxing can’t seem to get their act together, and they don’t have any good fighters coming up. UFC has done a wonderful job. Every time I give them a chance, I say ‘Wow, that was great.’ If you give them $30 on PPV, they deliver. With boxing, $40 might be a one-minute knockout. How many times I have thought, ‘I just wasted 40 bucks.’

Bob Sturm, sports talk radio host on “The Ticket,” is one of the few members of local sports media on board with ultimate fighting. “I was a big boxing fan, and the problem with boxing has been well documented,” Sturm said. “Boxing can’t seem to get their act together, and they don’t have any good fighters coming up. UFC has done a wonderful job. Every time I give them a chance, I say ‘Wow, that was great.’ If you give them $30 on PPV, they deliver. With boxing, $40 might be a one-minute knockout. How many times I have thought, ‘I just wasted 40 bucks.’

“Boxing will probably always have an audience, especially with Hispanics, whose fighters dominate the lower-weight class,” Sturm said. “But with the suburban general American sports fan, they get bloodthirsty. This is what they like, it is their own sport, and they feel like they own it. It is fantasy in some ways, but aren’t all sports that way for the fans?”

The racial aspect of ultimate fighting is something the promoters don’t want to talk about, but it does influence its popularity. White America has always held out for the Great White (Homegrown) Hope in boxing, but it hasn’t happened in 50 years. Boxing champions are now Hispanic in the lower-weight levels and African-Americans or Russians in the heavyweight division. To younger white sports fans, a seemingly quiet and calm Travis Lutter — 6’2” and 200 pounds — looks more like them.

Bert Sugar, 70, a boxing writer and host of Classic Ringside on ESPN, hates ultimate fighting and doesn’t mince his words. “It is nothing more than a bar fight without broken beer bottles,” Sugar said. “They get on the floor and beat the shit out of each other. Pro wrestling is cartoon violence, but this is real violence.”

Sugar said fighting has always been a mirror of society, with the ones on the bottom of the ladder succeeding. That’s why, he said, the Irish and Jews and Italians dominated the first half of the 20th century, blacks and Hispanics the second half.

Ultimate fighting, he believes, is giving white America more of what it wants to see. “A lot of people don’t follow Latino fighters for whatever reason,” Sugar continued. “Some don’t identify with black fighters. It is certainly a cultural thing. The fans of [UFC] go to the fights, or watch on the couch with their buddies and drink their beer, and they see guys who look like them. And we all know that whether you are black or white or Hispanic, you like to root for people who look like you.

“But I still think boxing is a sport, and this isn’t,” the writer said. “It is a tough-man contest that has been gussied up. I’d rather go out and watch a car wreck. But that is what they are selling here — a car wreck in a ring. I guess that is what these young guys want to watch.”

Lutter knows the fans are interested in the car wreck, and he doesn’t care much. The exposure on Spike TV will help his jiu jitsu teaching business at the very least, and he might have the chance to make his “comeback” during a time when the purses and sponsorships are growing with the PPV revenue.

What Lutter likes most about the sport as it has evolved is the respect fighters have for one another. Some of this may come from having the high school wrestling background, some of it from the mental and emotional discipline conveyed through martial arts, and part of it is no doubt the fact that most of these MMA fighters think they aren’t getting paid enough right now.

“The respect is always there in ultimate fighting,” Lutter said. “We don’t do all that trash talking, and we don’t have this feeling of hatred for each other. If you beat me, you were the best that night. If I beat you, I was the best. I don’t think fans see that in boxing, and I think that is part of the attraction here.”

So why does he do it? “I always loved competition, and after college wrestling was through for me, I still had that competitiveness,” Lutter said. “When I studied martial arts and won those events, I just looked to the next level. Until recently, the money hasn’t been right to do it full-time. But that is changing now.”

This year, ultimate fighting is predicted to out-gross boxing in Las Vegas. The current stars of the sport — Tito Ortiz, Ken Shamrock, Chuck Lidell, and Randy Couture — will make their nut. UFC wants to expand it from Nevada and California to sites around the country. The company has announced there will be a championship match in Houston or Dallas in 2007.

Lutter realizes that at his age, he has about five or six years left to reap the rewards in his sport. If spending the worst six weeks of his life making a tv show is the way to go, then that’s what has to be done. He wants to be there when the money gets right and he can work at a good wage for a championship.

“The reason people like this [sport] is that there are just so many ways to lose. When you have that many ways to lose, it creates an exciting sport,” Lutter said. “But I have learned there are also so many ways to win. Some ways are in the ring, some are outside. I never paid that much attention to the things outside the ring. I am paying a lot more attention to that now.”

If Lutter becomes that star of the Spike TV show, he will be able to write his own ticket. But even if he doesn’t, his name will be out there as one of those reality show fighters who gets put on a bill because of name recognition. And even if that fails, he will have his gyms where police officers and firefighters and young guys with big dreams go to be trained by a black belt in jiu jitsu.

In the next six weeks, the fight club world will know whether Lutter will be able to move on to the fame and the big bucks. “Whatever happens on the show … I expect to be a contender for the title,” Lutter said with his quiet and unassuming confidence, such a contrast to the hype that surrounds his sport. It is that confidence, perhaps, without any hint of bragging, that makes it hard to bet against this guy.

You can reach Dan McGraw at dan.mcgraw@fwweekly.com.